In 2018, IDFA DocLab launched a partnership with the Artis Planetarium to present dome-based immersive artworks during the festival. Some selections are expressly designed for dome projections, while others are installation or headset-based DocLab selections, adapted through an initiative of DocLab, Artis, WeMakeVR and the Netherlands Film Fund. As with any artistic format, there are certain technological, physical and social parameters that affect content, narrative and style design, making it a unique artistic and presentation opportunity.

For the 2025 programme, FEEDBACK VR, UN MUSICAL ANTIFUTURISTA was selected for adaptation. We talked to both the two sides of this collaboration – the artist creator Claudix Vanesix and WeMakeVR’s Avinash Changa – about adapting FEEDBACK from VR headset to dome projection and the general approach to creating art works for a dome.

(The conversations happened separately, but are edited together for flow.)

Avinash Changa – Years ago, Caspar [Sonnen] had this idea about the dome of the planetarium – isn’t that just a giant headset that we could put people in? I get the thought, but it doesn’t really work like that, because you only have half of the headset. When you’re wearing a VR headset, you simply look everywhere, especially below the horizon. We can’t just convert the file to play in the dome – that’s just not the case, because from technical, creative, narrative perspective, from an interaction perspective, from an embodiment and sense of presence perspective, all of these things are fundamentally different. So, technically, yes, it’s half of a really big headset, but it’s also not in many ways.

No one really had any inkling, any idea what the consequences would be of taking a piece from a VR headset to a dome. Would it work? We did not know if the experience would make sense to the audience, would be enjoyable? Would the narrative come across, versus content that was designed specifically a dome type presentation?

Editorial⎜IDFA Doclab 2025: OF(F) the Internet

Why choose FEEDBACK as the one to convert?

A.C. – It was three factors. Casper really being passionate about the piece, myself being interested in piece from a conceptual and narrative perspective, and the team clearly being very open.

We look for interesting things that are happening in the domain. Caspar was really excited about FEEDBACK. When I reviewed the piece, I saw it was interesting from a creative and a conceptual standpoint. For me, personally, every project I do needs to explore and advance the body of work in the immersive landscape. With dome-type presentations, that’s an interesting domain. But it’s not enough to just have a piece a VR piece and do a technical conversion. You want that project to have conceptual value, and I want to then see if we can crack the challenge of keeping the narrative, keeping the concept intact, while moving into a completely different presentation format.

A big thing in the VR version of FEEDBACK is that you as a user have a lot of agency, you can look around, you can engage, you control the frame, whereas in a in a full dome type version, you don’t have that control. It’s a very different dynamic between maker and audience. In film, you have a director controlling the frame, and you have a passive viewer. When you go into a headset experience, that power dynamic changes. The director is a creator of an environment, of a world. What used to be your passive viewer becomes a guest in your world, a guest that has different levels of agency. It reframes how you look at yourself as a maker. When we then take the step to a dome, you explore this interesting middle ground: people can still look around and control what they’re seeing, but it’s closer to being in a really big IMAX theater, and we’re back to more of a viewer/director relationship.

You’re also dealing with circular seating, so in what areas of the screen do we see certain parts of the narrative unfolding? That is an interesting creative challenge, what can we learn in terms of how you keep your narrative intact, given the nature of the venue?

And when you watch in VR, you’re on eye level with the characters. You are with them. They’re standing around you in the 360 space. That doesn’t work in the dome, but you still want to convey that.

So when I looked at FEEDBACK, there were a lot of these questions that we don’t really have answers for. Can we find them from both a creative and a technological standpoint?

And the last factor in deciding for this piece was a meeting with the team. Because I want to know who are these makers, are they open to having a creative collaboration? It’s more fun to have an open dialog and explore these things together. It was fun to spend a lot of time with them on this.

Claudix, you and the Peruvian collective AMiXR adapted your piece from a VR headset to dome projection, but you had already had one change of format for FEEDBACK before that.

Claudix Vanesix – The piece was a 30-minute performance first, back in 2021 in a very small venue in Cusco. It was sincerely one of the most exciting performances I’ve ever done. No one who saw a performance was remotely ready for what they were about to see, because it was not very common to see headsets in Peru back then, and we would livestream from our headsets to create a juxtaposition of our physical bodies with our avatars in real time, like in VRChat.

But we always knew we would make a VR film, actually. We knew we wanted to design a circular, immersive version, so I spent a year and a half writing an interactive script. Everyone was pushing us to do an interactive piece, because that’s what will be appreciated in the industry, because we are all running this race of who makes the most technological next thing. But for our team, for the kind of funding that we had access to, it was just unrealistic.

So you and AMiXR made made the 360 VR version, but then you got another opportunity to adapt it, this time to a dome projection…

C.V. – We were very lucky. We got the interactive grant from the Netherland Film Fund to make this adaptation, and we worked in collaboration with WeMakeVR, which is led by Avinash Changa, who has a lot of experience with domes.

I remember being very excited about the dome giving us the opportunity to show the film to multiple people at the same time, which is what we wanted so much. And there is that sense of theatricality back, the convivium of me experiencing this at the same time that you are, and your reaction also impacts my reaction. There is a sense of shared experience for the audience, which I think is really cool. But I also felt a sense of loss of intimacy, because when you are in your headset, you can turn around and the experience is still focused on you, and in a planetarium, when the performers turn around, you are no longer on the privileged side of the experience. This was very hard for us to design for, and we tried to find an equilibrium so that all of the directions would have some time being the privileged view.

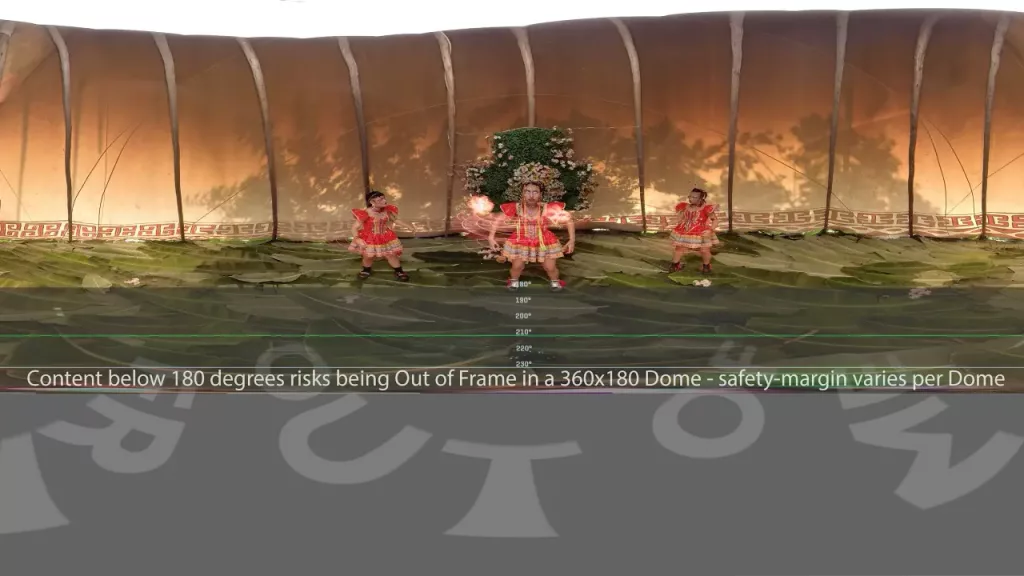

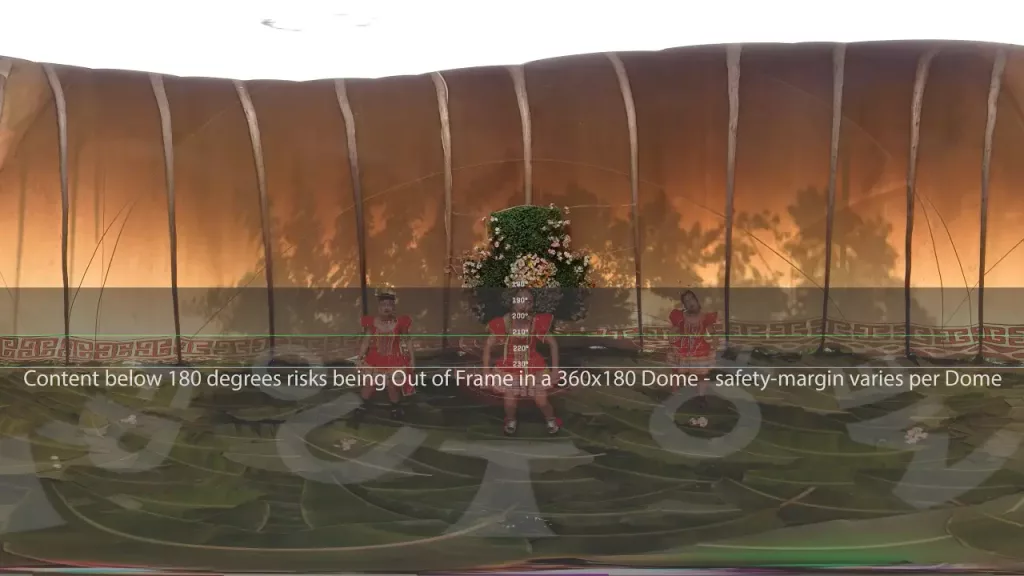

It was a big challenge. It was the first time that the team approached dome, and there is a lot of post-production that needs to happen in order to take to make the best use of the space on the 180 degrees that you have available for projection. So it was a process of two months of meetings with him and creating small guides for ourselves on how to convert 360 stereoscopic VR into 180 monoscopic dome, with the specifications of Artis Planetarium.

Crafting Immersive Narratives, with Claudix

When you reconfigured, did you have to recut or redesign any of the actions that were happening in the piece? Or it was just a matter of reformatting?

C.V. – There was a lot of redesigning the image. It was not like we have a sphere and we cut it in half, and that’s the half you see, because we had some action going on in that lower part of the sphere. Avinash taught us some of the workflows that he had already created for converting 360 to 180 and this included compressing the image, not just compressing the size, but compressing the pixels. So if we have a sphere, we can compress a lot of the sky into itself in order to get more of the lower, below half of the film into the upper half of the projection. For instance, because we compressed the sky into itself, now we can see the shoes of the performers. But if you compress a part of the sky and then suddenly one of the performers raises a hand, then the hand completely disappears because it was compressed. So we had to create a lot of masks for the first and last scenes, which was 360 video.

A.C. – The horizon in a dome is at a different level, and the dome is only half what the headset would see. Let’s say we film something in 360 in a park. That means that a lot of the content, the trees, the top of the foliage of the trees, would be visible, but you wouldn’t see the tree trunks because they’re [below the line]. But from a narrative perspective, we do want to see that, so we push all of it up. We can just compress the sky so it doesn’t need that much screen space. You are physically lower, but it still feels kind of natural. But let’s say we would do the same scene inside of a building. You would then see that the ceiling warps and it doesn’t feel realistic anymore. So depending on the dome that you’re presenting in, you have to decide what your content is going to be. If it has already been created for a VR headset with a full 360×360 image, then there’s a lot of creative work to be done: What do we want to see? What don’t want to see?

For example, there’s a part in FEEDBACK VR, UN MUSICAL ANTIFUTURISTA where you have the snake on the floor, and the snake is slithering towards the characters. When you saw that in a VR headset, you physically were looking down at the snake. In a dome that doesn’t work, because the snake would be gone. So in this case, we had to reposition that entire part of the image and the snake to be above the horizon. We had to curve a bit of the floor to still show enough of the characters. We also have to reposition the height of the characters, because normally their feet would be cropped out and you would only see the top of their torsos, so they had to be moved up.

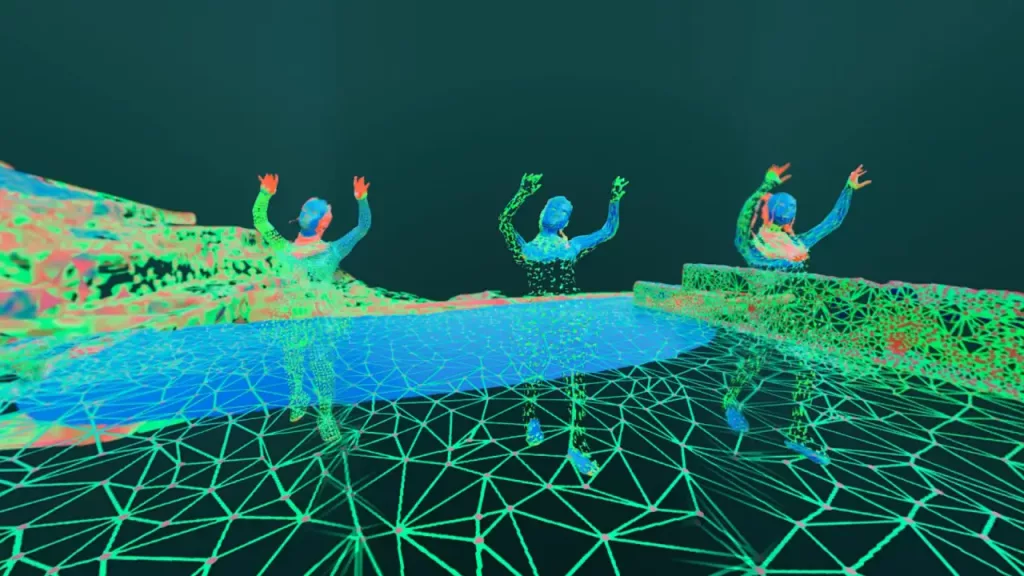

If you do something in a game engine, and you still have your pipeline ready to go, that is relatively easy to do, you can just take those 3D assets, reposition them and rebuild your scene. But if it’s already baked in your headset because it’s a 360 video, it means you have to play with distorting the lenses, warping the footage, repositioning or recompositing, in this case, the snake.

You also lose maybe 100 degrees of the image that would be behind you, because there is no behind in that kind of setup. [That content would be visible in a VR-headset just by turning around, but with Artis’ circular seating, a viewer cannot easily see that part of the screen behind them.] So then you have to determine, per scene, how do we rotate the image, where is the point of interest? Again, this was tricky with FEEDBACK, because the characters are not always as a group in the same place. So that means that if you leave that and you just do a straight conversion, you lose significant parts of the narrative content.

C.V. – We had to change a lot of things in the animation as well, for it to not be so close to the camera, but also not be so far away from the camera. And we had to try a lot of new things because we were already into the mindset of our stereoscopic editing workflow, which means that any new change or object that you add to the scene, you have to duplicate and duplicate it with small difference of a few pixels in one eye and in the other. Already the post-processing for the VR was very hard, and then having to let it go to start the post-processing for the dome was hard. Also, our eyes were very drunk on digitality, like, “What are we doing again with this film? We are compressing this part of the film so that we can see the shoes. What about this scene? What if we don’t see the shoes? Do we need to see the shoes? No, let’s just put it from the from the chest up. But we got this award, so we should, explore all of the possibilities of the best adaptation. Yeah, we should. And what about the audio? But it’s 5.1. What does that mean? Oh, all the voices, we have to extract them and put them in a different channel.”

When it comes to animation, if you’re building something in VR for a headset, you’re playing with the depth a lot. In the dome, does that also transfer from VR or do you also have to change that depth of animation?

A.C. – With animation, what we’re talking about here is z space, stereoscopic depth. In cinema, that’s framed as 3D. So when we’re talking about animation for FEEDBACK VR, UN MUSICAL ANTIFUTURISTA, yes, the animation was made in a 3D engine. You use something like Maya or Blender to create these things, and the pipeline of the headset and the renderer that sits between Unity or Unreal and the headset, automatically projects that image for both eyes. So a character, in Unity placed 10 meters away from the viewpoint of the camera in VR is going to feel 10 meters away because the stereoscopic offset. Now, when you don’t present in a VR headset, but in a monoscopic display, you don’t have depth because there’s no stereoscopic/3D image. So you choose either the left or the right eye content.

In a non-stereoscopic dome like the planetarium, you can still get a sensation of depth, but you do that by your compositing, by how large we make a character appear, against what other objects. So for example, once a main character in FEEDBACK grows into a giant, we want to make her feel like she’s a giant. How do we do that? In this case, by scaling her into the zenith. As an audience member, you feel that she’s large, because you’re tilting your head back, and you have the physicality of the other audience members next to you, so you feel that that difference in scale. The other tool, if we don’t play with the height, but want to have a sense of scale in Z depth, you put objects along the path in that Z depth for reference. So then you don’t have stereoscopic imagery and projection, but you still get a sensation of depth and scale.

Sound is so important to immersive work, especially in VR headsets, where sound often serves as a trigger for where you look. How was it adapting the original sound design?

C.V. – Our sound designer, Jorge Pablo Tantavilca, had many nights without sleeping working on this conversion. What I can say from their experience is that one channel mono, two channel stereo, five channel ambisonic, and then 5.1 is a workflow that brings multi-dimensional complexity to the work of an artist in a way that it always felt like expanding, and it’s scary and it’s challenging, but at the same time, it’s really rewarding, because it helps us understand how by designing assets, we can shape the sense of reality.

So the more divided assets we have in the audio gives a stronger perception of realness in a spatial experience. Also, there are some parts of silence, and in the dome version, I enjoyed those silences so much, because how can a room full of people be silent? I feel like there was this joy of playing with these assets and an almost artisanal approach to the digital files.

A.C. – We knew the venue had a 5.1 channel sound setup, but their extra speaker was a Zenith speaker. So that means that we have, yes, these four channels – north, south, east, west – and we have a fifth channel at the top of the dome. But there’s no standard to export in this format. So I spend a lot of time physically in the dome to map it out and reverse engineer how that system works.

Since we also reformatted the visuals, [we had to rework the sound mix in that sense as well]. But since there’s no proper frame of reference, there are no tools. We have to look at every sound, every orientation. That was difficult for them, because in their studio, they could not replicate the type of speakers and channel setup that the dome has. So they were working in the blind based on these technical specs.

The fact that we were able to tweak things literally right up to that last moment before the doors opened is just because we have this kind of relationship with the venue, but in most other cases, you would want to have better tools to know what the specs of this venue are and know how to deliver it in a way that it is going to work. The vendors that do the technical installations at these domes – they’re technicians, but they’re not content creators, so they generally don’t document the capabilities of the system in a way that makes sense for makers. So we’re still at the phase that you have to reverse engineer.

A.C. – There are many challenges. These conversions require you to have access to technology, to headsets, to software, to hardware, to be able to render these pieces and render them fast enough. Also, when you’re creating something for a dome, you don’t have access to a physical dome, and we don’t have any commercially existing ways to view dome-type content. I created a tool that allows you to connect your editing software to stream to your VR headset, which puts you in an actual dome. Then you play out the content in a one-to-one representation of what it feels like in an actual dome.

C. V. – It was technologically very challenging for us, but we did it after many final renders, many final versions.

There are very few differences between the two [versions], like some digital assets – when it’s a VR one person experience, these assets are focused on the point of view that we designed, and then for the dome, they were shared all over the space so that everyone can see it. But it’s just very minor details. The narrative is the same. We considered making some adjustments to shorten it, but it is sequential, and we didn’t want to take away any of the learning steps that the characters have before they reach the beginning again.

If you had gone straight to the dome from the performance, do you think you would have configured the piece in a different way?

C.V. – Absolutely, it would have been way more trippy. And more like a mirror, designed as ‘oh, I tried to go through this place, but actually, I’m already entering…’ I would have played a lot with the sense of end and beginning of reality in a way so that multiple directions can experience the main activity happening. We would have made the shootings different, with the camera lower, not so much at the level of our eyesight but almost in the floor. We probably would have played more with this giganticness that would have allowed us to take over the whole screen. It’s important to know what your preferred medium is. And adaptations are adaptations.

It seems like even if you are specifically a “dome” artist, you’re still running into this difficulty of the work needing to be constantly adapted. Is there a general basic framework for making a dome piece, that then just needs adjusting for venues?

A.C. – Every dome is different – the horizon, screen position, recline of the seats, brightness and resolution of the screen…

If you create anything, and you know the action is always going to be in 180 -200 degrees field of view, then you’re always going to be safe. Pretty much every dome has a zenith, there’s always something right above your head. And from creative standpoint, we can play with that. We can do something that falls from the sky down, or something that goes up into the sky, and we have 180-200 degrees width. So if you know that, and your content sticks within those parameters, you know from the get go that you’re going to be quite universal in terms of most domes being able to present it in one way, shape or form. After those basics, you might need more resources in adapting the piece, because then it’s then it’s a content adaptation, not just a technical format.

But the other thing is that every dome has different sounds. There’s no industry standardization yet, like we have in cinema. If your original piece was made for stereo sound, then it’s always going to be stereo, there’s no degradation in what you originally made. But if you started creating for, let’s say, 64 or more channels, then bring that to a venue that has a standard setup, you’re going to lose the larger content if you don’t properly remix it for that venue. So what that means for makers is to have a very well-organized project in terms of sound, that you have all of your different sound layers, you have someone that is capable of doing different technical mixes, and, in some cases, even different creative mixes.

Now that is where we encounter a significant hurdle. We usually don’t have those kind of budgets and resources to do those kind of mixes, so then you always end up with a version that could be more immersive in terms of audio, but we don’t have the tools or the funds to make, to use, to optimize what we’ve created.

If you work from the lowest common denominator, from a maker’s perspective and from the venue’s presentation perspective, that checks a lot of boxes. But from an audience experience, you leave a lot of potential on the floor, because you want more immersive audio, you want the visuals to pop. You want to feel part of that experience. So that’s frustrating, because the tools are physically there in the dome, but those tools in between to make that work, to utilize all that potential, they don’t exist.

I’d like to create tool sets that allow you to try your content in different sizes of domes or different seating arrangements in the audience, because that affects the way you deal with your content. With more practice, you start to expand that toolkit so that it becomes easier to take a VR piece of content, to go through this and know that if this is our output, that’s the path that we take. You also need to have the creative understanding of what does the story do when you suddenly tilt the horizon or lose part of the image. So that’s kind of your vocabulary that needs to be built.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.