Bruno Ribeiro describes himself as a show director and media artist, with a straightforward guiding principle: to create experiences that transform perception by working with image, sound, space, and time. This isn’t theoretical—it’s a way of approaching creation as a continuum, where an installation, a concert, a monument, or an immersive projection system all answer the same question. Not “which technology?”, but what kind of attention do we produce, and for which audience.

Cover: STROBOSCOPE by Bruno Ribeiro

In his trajectory, cinema isn’t a starting point to move beyond—it’s a constant. Cinema as rhythmic writing, as narrative tension, as the art of staging. Ribeiro himself speaks of a “hybrid” vision, blending mise-en-scène and narrative tension with a wide range of tools (mapping, light, interactive systems, real-time engines, AI). What evolves, however, is the frame: in Ribeiro’s work, the “film” is no longer limited to a frontal screen. It can become a walk-through experience inside a monument, a light sequence that organizes a public square, or a collective moment in which the venue—and people’s reactions—become part of the setup.

This portrait deliberately keeps a modest tone: no glorification of tech, no promise of “revolution.” Just a clear trajectory, and works that, each in their own way, slightly shift audience habits. To understand that shift, three strands speak to each other: his live training (and VJing) as a culture of rhythm and the collective; the heritage axis of AURA Invalides as a “cinema” experience scaled to a site; and a recent installation like 48 Pillars, which condenses this grammar into a short, readable, repeatable gesture.

From VJing to showmaking: learning the audience “in real time”

Before talking about architecture or immersion, we have to talk about live. Live is a world where the image doesn’t exist alone: it coexists with sound, a stage, a crowd, the unexpected, an energy that rises or falls. And it’s a world where success isn’t measured only by the beauty of a visual, but by its accuracy in the moment: does it carry the event, does it support it, does it breathe?

Ribeiro explicitly claims this “live performance” and experiential horizon in the general presentation of his work—and in his earliest artistic approach. His portfolio also documents interventions where the image is conceived as one component of a larger stage system—through, for example, “live visuals” credits within scenography and lighting design teams. This kind of context is formative: it forces you to understand what an audience actually perceives, and what it doesn’t. It also forces you to accept a reality that can be frustrating, yet healthy: an audience doesn’t “decode,” it feels. It doesn’t analyze an intention; it receives a rhythm, an intensity, an atmosphere.

This live logic partly explains why Ribeiro moved toward immersive and monumental forms: they extend an intuition acquired on stage. When the image becomes spatial—when it expands into a volume, when it lights a place, when it synchronizes with sound—it no longer serves only to illustrate. It serves to organize a group: to slow down, accelerate, gather, disperse, invite people to look up, to move, to share a point of view.

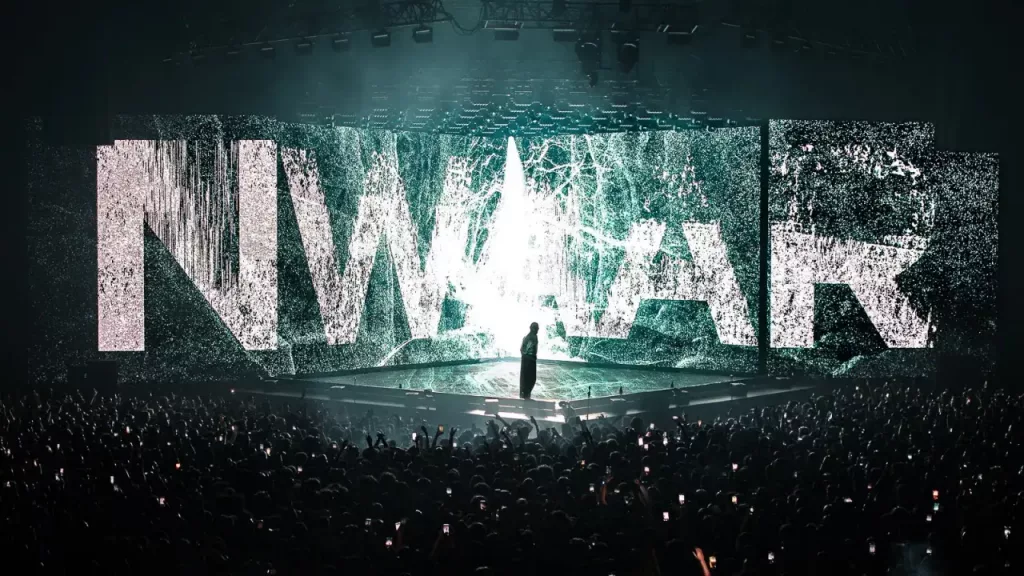

Several external sources, beyond his own sites, describe this lasting relationship with the worlds of music and live shows (including collaborations with Damso and Muse) as a core axis of his practice. Again, the point isn’t to “prove” legitimacy through names. The point is to grasp what that culture does to his writing: concerts teach staging; concerts teach constraint; and above all, concerts teach that the audience is material—an element of the device, not a simple recipient.

AURA Invalides: telling a story with a site, without forcing the line

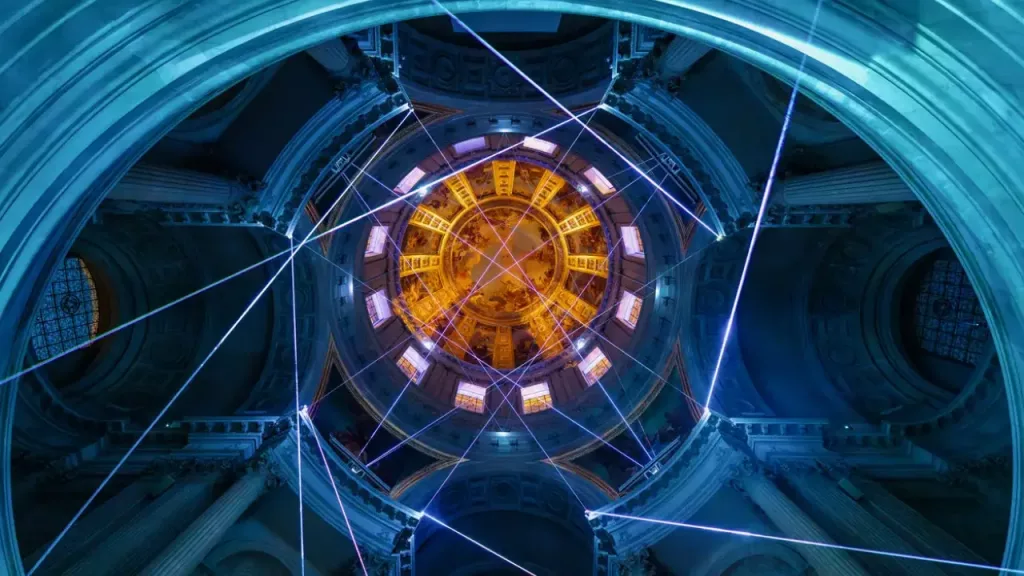

As a clear example of his approach, AURA Invalides (a concept produced by Moment Factory and replicated across several venues worldwide—here with the Musée de l’Armée – Invalides and Cultival, in collaboration with Jean-Baptiste Hardoin for staging and artistic direction) is instructive because it is both highly framed and highly open. Highly framed by its format: an evening experience of about 50 minutes at the heart of the Dôme des Invalides. Highly open because it doesn’t impose a seat and a screen: it offers a light-guided walk-through, where visitors explore several spaces before gathering beneath the dome.

Light, orchestral music, and video mapping “animate” the interior of the monument and reveal its heritage and décor. The premise is a collective experience under a painted dome announced as 60 meters high, where classical architecture and digital creation enter into dialogue. The language used is fairly sober, and that’s precisely what matters here: AURA doesn’t present itself as an “attraction,” but as a narrative activation of the site.

The story is structured into “three movements” on the official website. Without over-interpreting, you can read in it a method close to cinema: progression, transitions, an emotional rise. The experience isn’t a continuous stream of images; it’s a composition that chooses when to show, when to let things breathe, when to gather gazes. And because the spectator is in motion, this composition must integrate a variable that traditional cinema rarely controls: the diversity of listening and viewing points. This is where the “audience” approach changes.

In a theater, the audience is a set of still individuals sharing the same frame. In AURA, the audience becomes a set of visitors who move forward, stop, regroup, and then reunite. The collective isn’t a backdrop—it’s a fact. There are constant micro-decisions (where to stand, when to move, where to look) and, despite that, a common thread. This is exactly the balance Ribeiro seeks in his work: leaving freedom to the viewer while maintaining direction.

Even practical information (stairs, sound intensity, flickering lights) reminds us that we are not facing an “enhanced film,” but a format that engages the body and perception. You may find that observation banal, but it is central for thinking about the future of audiences: image culture has become domestic, individualized, fragmented. AURA offers something else, without claiming to replace cinema: an experience where duration, place, and being together become values in themselves.

LED domes: new territories for cinema

In his collaboration with the American team at Little Cinema for COSM, what stands out is a spirit of innovation: next-generation venues/domes that aim to give cinema back its dimension as a collective event, through a highly immersive setup and a simple promise—“come to the theater to experience something different from home.” A clear intention, with dome-shaped LED screens, surround sound, and an immersive experience designed to bring audiences back to theaters in the face of streaming’s rise.

The “Shared Reality” format around The Matrix is a fully-fledged experience in which the film unfolds “around” the spectator on a LED dome (COSM notably communicates about an 87-foot LED dome). The point of that detail isn’t to fall into technical fascination. It’s to signal a transformation of the offer: cinema is no longer only content; it becomes an experience frame. And this frame, very often, comes with behaviors and rituals: arriving early, staying after, talking, consuming, turning the screening into a social appointment. COSM isn’t limited to cinema; it also develops other immersive experiences (sports, shows), which places Matrix within a broader “entertainment venue” strategy—still largely confined to North America or a few Asian venues. In Europe, the recently renovated Prague Planetarium has installed a 22-meter-diameter dome—one of the largest in the world—equipped with LED technology featuring around 45 million diodes to deliver the image… powered by COSM’s technology.

The arrival of these new venues highlights one thing: the work of an artist like Bruno Ribeiro is part of a moment in which the boundaries between cinema, spectacle, and installation are being reshaped. And above all, a moment in which the audience question returns to the foreground. Not “how do we capture attention,” but “how do we make people want to share an experience again.”

48 PILLARS: proof through simplicity

48 PILLARS offers an essential counterpoint to AURA and large projection systems: it is a short, structured work that doesn’t depend on exceptional heritage or a global franchise. It shows how Ribeiro can sustain his language with an economy of narrative means: a matrix, a rhythm, a relationship between light and sound, and an audience that moves.

The installation is organized as a matrix-like structure of pillars, like the keys of a monumental piano, articulated around a light-and-sound composition. The presentation context at Llum BCN, in the courtyard of a museum (Museu Can Framis), confirms a concrete point: the work is designed for a flow of visitors, for evenings, for a repeated and shared experience.

What matters here is the discreet social effect produced by a well-calibrated light work. An installation like 48 PILLARS doesn’t impose a story. It proposes a situation: people stop, circle around, wait for the right moment, sometimes come back to see it again. And by doing so, they become an “audience” in the full sense: a group gathered by shared attention. It’s a simple gesture, but it may be one of the most important today: reminding us that digital and immersive art doesn’t necessarily need to “do too much” to rebuild a sense of collectivity.

This is where cinema returns, in an underlying but obvious way. Cinema was born from an illusion of movement, a rhythm of images, a relationship to retinal persistence. Ribeiro often works in this territory without underlining it: he composes sequences, fine-tunes transitions, plays with the sensation that time thickens or accelerates. And when it works, the result is less spectacular than precise: a moment of alignment between a place, sound, light, and people.

It is also in this spirit that he founded Stroboscope as a studio: a framework for production, collaboration, and the making of experiences that “draw inspiration from cinema and music” and aim to bring audiences together around shared narratives. The keyword matters: “bring together.” Not to inflate the ambition, but to recall something concrete: when immersive creation works, it doesn’t reduce to an effect. It proposes a social situation—sometimes calm, sometimes dense—that changes how we stand together in front of images.

Ultimately, the through line is clear. Bruno Ribeiro isn’t trying to replace cinema. He is trying to extend what cinema does best: create shared time, build tension, produce a common memory. Whether through the walk-through structure of AURA Invalides, the industrial signal represented by COSM and its “Shared Reality” experiences, or the structured restraint of 48 PILLARS, the same ambition returns: giving the audience an active place—without asking them to “participate” in a gimmicky sense—simply by giving them back space, duration, and the possibility of being together.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.