Phenomenal friction. When the New Media team at IDFA came up with this title, they knew it would reflect a recognition of tensions around the world, but the team had no idea that it would land in the midst of a war and public outcries that stirred up the festival, leading to several filmmakers – including immersive makers – pulling their work from showcase.

Phenomenal friction, as described by Caspar Sonnen, head of New Media, reflects a landscape where emerging technologies are changing how we see the world around us, but also one where we are still encountering and challenging each other’s identities and mindsets in the physical space.

This year’s DocLab and immersive exhibition brought together over 30 pieces from the most diverse set of artists and makers thus far, allowing the audience to encounter worlds not just different from their own, but also created by those living in the other worlds.

Take Natalie’s Trifecta, which won a Special Jury Award for Creative Technology. It’s a fever dream immersive experience encompassing three of the artist Natalie Paneng’s worlds – her studio, a gallery of her work and her dreamscape. There are dozens of Natalies everywhere, in many forms, floating and staring back, speaking directly to the viewer about her artistic process, the meaning behind her work and her desires of utopia. Moving through the portals, you have the chance to solve puzzles, listen to stories and get close to her digital artwork.

The jury’s statement that “it’s also completely bonkers, applying VR techniques and artistic styles that shouldn’t work together—except they do” is incredibly apt, and this is unlike many pieces you’ve seen before in a competition.

Going back home: Mother VR is another exploration of two worlds – the inside of a women’s prison in Chile and various scenes from the incarcerated women’s families back home. The straightforward 360 video places the viewer in different spaces of the prison, bearing witness as women spend time together, do their daily work and participate in artistic workshops (run by the filmmaker in a larger, long-term program to engage the women). But those incarcerated in Chile are not allowed to have any contact with the outside world, so the filmmakers use VR to bring them together with their loved ones.

The second part of the work features 360 “postcards” from their families, inviting the women (and the viewer) virtually into spaces that have meaning to them. The piece switches between those spaces and the prison, watching the reactions of the women watching their loved ones in VR headsets.

Some of the more interactive VR pieces evoke a deeper awareness of your body and call viewers to experience their body in a different way.

In Traversing the Mist, artist Tung-Yen Chao builds an extended or new world of the Taiwanese gay sauna he first created in his 2022 piece In the Mist. But where that was a seated 360 experience, this piece allows you to not only move through different rooms, but to do it with two other participants. The viewer takes on the form of a young, naked man, the reflection of whom can be seen in the mirror of the elevators (alongside the other two participants in the same form). Flashlights floating in the space can be picked up to illuminate the cabins and lockers as you explore the spaces. In doing so, you become part of a surreal dream world that feels less voyeuristic that In the Mist.

A beautifully animated piece, Emperor puts the viewer inside the brain of a man with aphasia as his daughter tries to makes sense of his mind and their relationship. While you never see yourself embodied as him, much of the piece is from his perspective. You experiences his struggles to communicate (through interactive vignettes) and periodically dissolves into his dreamworld of past memories.

In perhaps the most strikingly simple yet powerful piece, Turbulence: Jamais Vu, co-maker Ben Joseph Andrews invites the viewer to understand his neurological condition, which challenges one’s sense of orientation, balance and spatial awareness. Turbulence, which won the IDFA DocLab Award for Immersive Non-Fiction, embodies the viewer not by putting them in “his shoes”, but by evoking a parallel experience in their own. Seated at a desk, a simple “edge” filter allows you to see beyond the headset to the objects and space in front of you. But the input is also reversed, and as you try to follow the tasks called for in the narration, you experience that exact sense of disorientation and frustration. This is the first of Andrews and co-maker Emma Roberts’ three piece exploration of embodied space and movement in VR systems, for which they also won the DocLab Forum Award.

DocLab has always had a wide definition of “immersive” and “digital storytelling” (and non-fiction for a documentary festival’s sake). The exhibition considered XR beyond the headset, having multiple pieces that could be experienced in collective ways and which explored the idea of friction – having people rub up against each other either physically or emotionally.

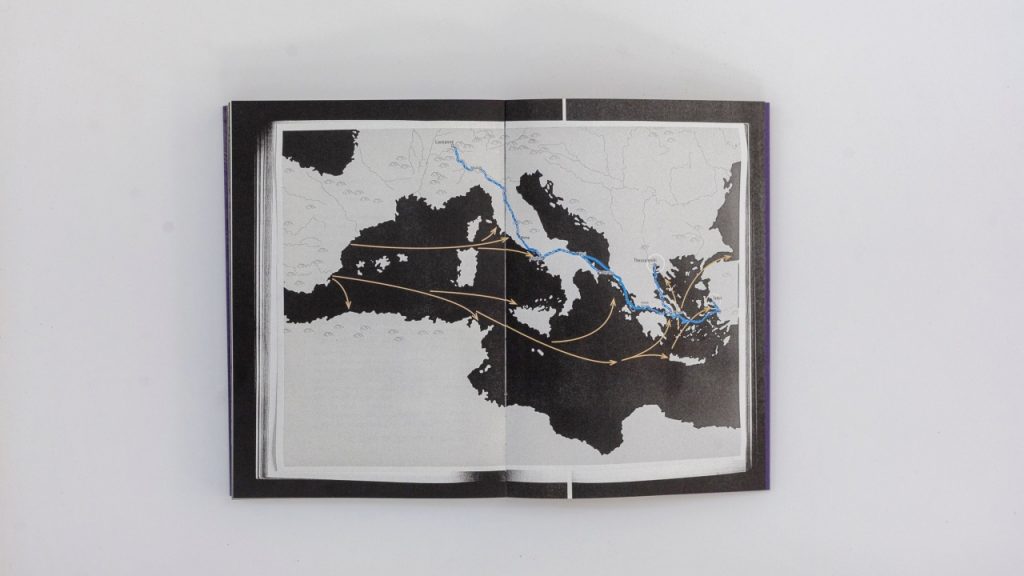

One of these, Borderline Visible, which took home a special mention for immersive storytelling, is a printed book (from the recently launched Time Based Editions) with accompanying audio track that guides the experience. Visitors could follow artist Ant Harmon’s journey from Lausanne, Switzerland to Izmir, Turkey one on one, sitting on couches in the exhibition space with headphones, or as a group experience on a cluster of folding chairs in the De Brakke Gronde theatre, turning the pages together to an amplified narrator. While there was no real interaction between participants, there is something to be said for a collective witnessing of a story unlike watching a film together.

For The Vivid Unknown, artist John Fitzgerald trains a generative AI model on Godfrey Reggio’s iconic Koyaanisqatsi. The resulting images were displayed as a massive three-screen installation in the theatre, which the viewer could watch from the seats or standing amidst the screens. But the installation is also interactive, generating new images and music in the same style according to the number and movements of visitors.

As it is everywhere these days, AI was powerfully in the forefront (and backend) of many works like The Vivid Unknown. With AI-generated work, often the concept is more interesting than the final result, but several pieces delivered on both sides.

William Quail’s Pyramid starts off as a walk with headphones, listening to indecipherable babble. As the participants enter a small theatre, the same babble can be heard over the speaker, but on screen are AI-generated subtitles. Do the subtitles make us hear it in a different way? In the last part, an AI-generated visual stream accompanies the subtitled babble with experimental fragmented images. Thus the question many are asking these days: who is creating the art?

But the most truly immersive and personal AI piece was Voice in My Head, by artists Kyle McDonald and Lauren Lee McCarthy. The experience starts off in a booth, as the user answers questions asked by a ChatBot: “If you had a voice in your head, how would it sound? What would you want help with?” The system takes a few minutes to process your answers and then uncannily recaps your perspective back to you in your own voice. From there, you exit the booth into the real world, as the “voice in your head” talks to you through an ear bud as you engage in conversations. The latter interactive part of course varies in success based on the prompts given and the conversations available to have.

DocLab invited attendees on a journey to allow “more space for friction, interaction and complexity”, and many of the pieces resonated with the idea of using technology to actually emplace us in thoughtful experiences. Stay tuned for more in-depth interviews and reviews of individual works in the competition and exhibition.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.