Between meetings at IFFR, the conversation with Isobel Knowles and Van Sowerwine quickly moved beyond the usual “how did you make it?” Because THE WORLD CAME FLOODING IN isn’t just another XR title on a festival slate. It’s a deliberate attempt to stage the afterlife of a climate disaster—the 2022 floods in eastern Australia—using immersion as a space for listening, moving, and rebuilding. You could label it “documentary VR” and stop there, but that would miss the point. Their real question is sharper: how do you represent what remains—objects, routines, relationships, memory—without turning catastrophe into spectacle, and without speaking over the people who lived it?

Cover: THE WORLD CAME FLOODING IN @ IFFR 2026 📸 Zsolt Szederkenyi

An immersive grammar built from decades of “cinema beyond the screen”

What stands out in Isobel and Van’s approach is continuity. Their step into XR doesn’t read like a trend-driven pivot; it feels like the logical extension of a long collaboration at the crossroads of film, animation, and interactive installation. They’ve spent years testing ways to make images physically inhabitable—inviting audiences to stand inside a scene, to navigate a narrative spatially, to treat the artwork as an environment rather than a framed object. In that context, VR is less a revolution than a tool that pushes an existing obsession to its limit.

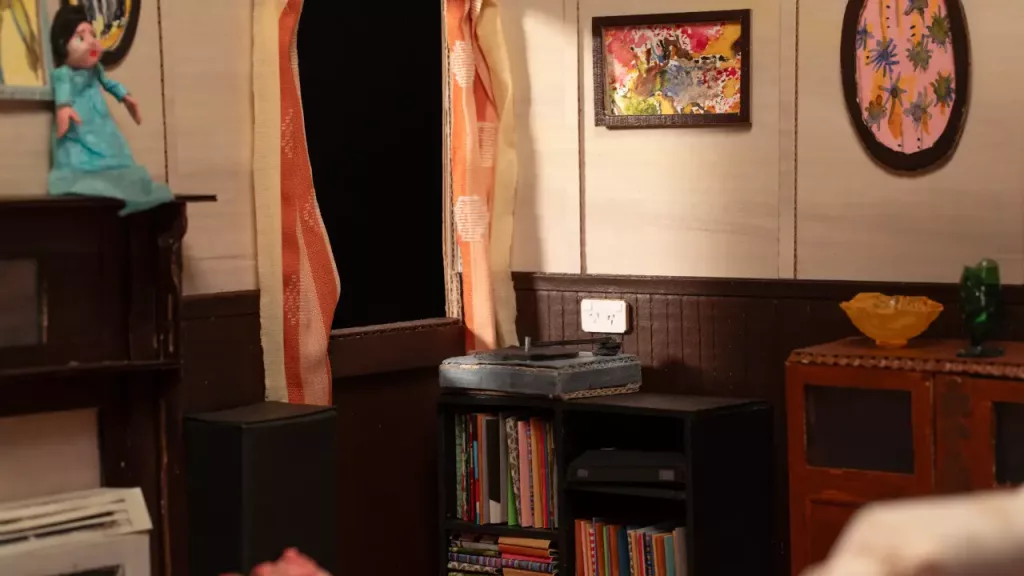

They often return to PASSENGER (2019) as a formative leap: a stop-motion 360° experience that taught them both what immersive animation can do—and what it costs. They describe the work as exhilarating and punishing in equal measure. The production demanded an almost absurd level of handcraft: building miniature landscapes at scale, designing continuous camera movement through a fabricated world, filming the character separately, then compositing everything into a coherent spatial experience. They don’t romanticize this. If anything, they emphasize the gap between an inspiring prototype and the industrial reality of delivery. But the lesson was decisive: when VR “clicks,” transport isn’t metaphorical. It’s physical. And handmade animation—imperfect, textured, visibly constructed—can feel strangely present in a headset, almost tactile.

With The World Came Flooding In, they keep that commitment to material craft, but they shift the technical center of gravity. Rather than relying on pure 360° capture, they move toward a more embodied sense of navigation and presence, while resisting the drift toward a sandbox of constant interactions. Their breakthrough was photogrammetry—not as a shortcut to realism, but as a way to remain faithful to their handmade practice while gaining the spatial affordances of real-time 3D. The idea is elegant: build miniature objects, scan them, and import them as volumes into a game engine. Suddenly, the hand-built becomes explorable.

Crucially, photogrammetry doesn’t produce “perfect” worlds, and that’s precisely why it suits their subject. When you scan a miniature up close, the surfaces reveal gaps, warps, holes; edges soften; the image becomes slightly unstable. This imperfection becomes a narrative asset. It mirrors the way memory works after trauma: partial, discontinuous, shaped by absence as much as by what remains. In their telling, the aesthetic isn’t decoration. It’s structure. A world that looks slightly broken is not a style choice—it’s an ethical one, because it refuses the clean, consumable image of disaster.

Climate, trauma, collaboration: when form becomes an ethics of storytelling

The core of the discussion is methodology: how to engage with a disaster narrative without extracting stories from people, and how to create a collaborative process that doesn’t retraumatize participants. They describe working with trauma-informed guidance to design the framework of meetings and workshops, and they speak openly about how this changed their approach. The central tactic is deceptively simple: make things together while talking.

Instead of recording testimonies in a direct interview format, they organized workshops where participants created paper miniatures—furniture, objects, fragments of domestic life—based on something lost. Sometimes the lost object is directly linked to the flood; sometimes it reaches deeper into personal history, into childhood, into identity. This is where their practice becomes very precise: the act of making shifts the tone of speech. People often talk more freely and more safely when their hands are occupied, when the conversation is anchored to a shared action rather than a spotlight. And the workshop isn’t a “method” that disappears into the background: what participants build becomes part of the work itself, and excerpts of voices are integrated into the experience.

They were candid about an outcome they didn’t fully anticipate: for some participants, the process offered a form of relief—not a solution, not closure, but a way to reframe loss as something shareable. That matters, because it repositions the artwork. It’s not just an object that circulates in festivals; WHEN THE WORLD FLOODS IN has obligations to the communities that fed it. This is where the ecological dimension stops being thematic and becomes structural. The work isn’t simply “about” climate impacts; it’s made through practices that aim to be non-extractive, careful, and reciprocal.

They also push against a lazy narrative hierarchy of disaster. Flooding doesn’t only destroy houses; it rewires a whole territory. Some people have a basement damaged, others lose everything, others find their city paralyzed—roads cut, cars displaced, infrastructures overwhelmed, routines erased. Different intensities, but a shared rupture of the everyday. In their eyes, focusing solely on the most photogenic devastation would flatten the truth. The psychological shock is not always proportional to the visible damage. And that nuance shapes the storytelling: the work is less about the moment of impact than about the unstable weeks and months after, when the environment looks familiar but no longer behaves as expected.

This perspective carries into their spatial staging. A motif they discuss is the “between” of rooms—spaces submerged in a kind of nocturnal darkness, where you cross from one pocket of domestic life to another. It echoes accounts of floods arriving at night, when neighborhoods become islands and people move by canoe through streets that have turned into silent water corridors. Yet they avoid literalism. Water can be suggested rather than rendered. Reflection can do more than simulation. The goal is not to reproduce the flood as spectacle, but to convey its lingering presence as atmosphere.

Then there’s the practical reality of immersive storytelling: if the interface interrupts the emotional thread, you lose the audience. Their response is blunt: test relentlessly, especially with people who are not VR-native. Watch where attention breaks. Identify where users hesitate or get confused. Reduce friction until it disappears. This is why their narrative remains guided—voice, progression, clear continuity—while allowing micro-freedoms: approaching objects, shifting perspective, exploring details without being forced into constant interaction. They also pay attention to accessibility elements like captions in VR, treating text as spatial and embodied rather than as a floating subtitle strip that can induce discomfort.

One of their most concrete design decisions is a “cinema mode”—a version that minimizes controller complexity, uses automated movement and fades, and reduces the risk of nausea. This isn’t a compromise; it’s a distribution strategy. It anticipates touring contexts, older audiences, regional presentations, and venues with limited mediation capacity. In short: it respects that “immersive” has to survive contact with real-world exhibition conditions.

Creating in Australia: a small, inventive scene constrained by distribution

The final part of the conversation turns toward the Australian context—and it’s refreshingly unsentimental. They describe an ecosystem that is creative but structurally fragile. The community is relatively small; people know each other; opportunities often come through relationships rather than stable institutions. Funding can be inconsistent, with XR frequently competing against more established formats depending on shifting program priorities. They also note that some galleries have been burned by the operational burden of immersive works—maintenance, hardware fragility, staffing needs—making them cautious about committing again.

So the question becomes: how do you keep making ambitious XR narratives when the infrastructure isn’t robust? Their answer is strategy, not complaint. They treat The World Came Flooding In as more than a headset experience: it’s an installation ecosystem. The paper miniatures can exist in the exhibition space. Photography can contextualize. Workshops can be part of the public program. Audio narratives can live beyond VR through other layers. This multiplies entry points for audiences and gives venues more reasons to host THE WORLD CAME FLOODINGIN – because even visitors who don’t put on a headset can still engage with the work.

They also speak about touring as a necessary extension of authorship. In Australia, where distances are vast and centralized infrastructures limited, touring forces you to think like a producer, a curator, and a technician at once. They describe planning a national tour through galleries, with exhibition runs long enough to justify setup complexity. Yet even with development support, full touring budgets remain difficult to secure. This exposes a structural gap that many XR creators recognize globally: making the work is one battle; sustaining its life is another.

In that context, they look with interest at institutions capable of handling larger flows—venues designed for immersive throughput where audiences can begin together, where mediation is built-in, where the economics are less brittle. But they don’t present this as a single “solution.” Their approach remains flexible: different versions for different contexts, different modes for different publics, and a constant awareness that distribution isn’t a downstream concern. It’s part of the creative equation.

What their trajectory ultimately says about Australia is a productive contradiction: a place where immersive narrative can be institutionally precarious, yet formally daring. Because constraints force invention. Because artists build hybrid models. Because the work has to be legible both as art and as an exhibition object, not only as a file. Programs and cohorts that support experimentation matter in this landscape, but so does the artists’ willingness to design for life beyond festivals.

If you had to distill our discussion into one statement, it would be this: THE WORLD CAME FLOODING IN uses immersion not to intensify spectacle, but to give form to what is hard to hold—loss, disorientation, the fragile continuity of domestic space after water has rewritten it. And it insists, quietly but firmly, on a truth the industry sometimes dodges: in XR, the real power isn’t the tech. It’s the framework—how you listen, how you collaborate, how you reduce friction so attention can stay with the story, and how you build a path for the work to meet audiences beyond the festival bubble. If ecological reality is becoming our shared horizon, the works that will matter are those that connect the intimate to the collective—and that figure out, concretely, how to travel.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.