First seen at the latest Venice Immersive, THE TIME BEFORE by filmmaker and animator Leo Metcalf is a deeply moving story told from a child’s perspective. Combining poetic storytelling with carefully crafted interactive design, the work explores memory, consciousness, and the fragility of perception through a hybrid of 2D animation, 360° video, and real-time interaction.

We spoke with Leo and interactive designer Michael Golembewski about the project’s long creative journey, the relationship between animation and interactivity, and the emotional terrain that inspired it.

A Journey Across Mediums

Leo Metcalf: After finishing my studies, I initially worked with NGOs producing radio programs on health, environment, and education, particularly in Madagascar and Afghanistan. That experience led me to filmmaking, beginning with the documentary Disastro (2017), about the Greek crisis. Gradually, my interests shifted toward exploring consciousness and how it emerges from the interplay of memory and perception. This naturally led me to virtual reality. I wanted to explore how immersive media could place the viewer directly inside another person’s experience and evoke altered states such as memories and dreams.

To pursue this, I studied animation at the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London, where I made THE EVERYTHING MOVE (2019), a 2D short film rendered in 360°. That project became a kind of testing ground for what would eventually become THE TIME BEFORE, both being set in the same universe.

From Isolation to Collaboration

L. M.: THE TIME BEFORE took around four and a half years to complete. The pandemic, my mother’s illness, and the need to take on side projects all slowed things down. I was working alone for a long time and had little experience with real-time engines like Unity. I came from a background in writing and filmmaking, where the timeline is the center of everything! The project file was quite a mess until I met Michael Golembewski, who became the interactive designer and lead developer. His deep understanding of interactive systems and his technical precision helped bring the work to completion.

For me, interactivity should never interrupt storytelling. In THE TIME BEFORE, it’s deliberately subtle—almost invisible. It accompanies the narrative rather than imposing itself. In the final scene, for instance, when the viewer sees their reflection, the character’s head gently follows their movement. It’s not an ‘effect,’ it’s a narrative gesture: you realize you’re in the story. This kind of micro-interaction deepens immersion without breaking emotional continuity. I like to think that the best interactive design is the one you don’t notice—but that changes everything in how you perceive the world around you.

Michael Golembewski, Interactive Designer

Two Versions, Two Audiences

L. M.: Immersion and interactivity were always central to the project. However, while Michael and I were still finalizing the build, I created a non-interactive “cinema” version by using overcapture: moving a virtual camera through the 360° environment (in some ways ‘deciding where the POV looks’) and exporting it as a flat video. I edited it in DaVinci Resolve, called ‘A Time Before’ and to my surprise, it was very well received at short film and animation festivals.

The interactive VR version, THE TIME BEFORE which had its international premier at Venice Immersive 2025, offers a more embodied experience, while the cinematic cut, A Time Before, worked well for people who have trouble experiencing stories in a headset, as well as offering the shared experience of a cinema screening. Seeing how each format shapes emotional engagement has been eye-opening. Funnily enough, for those who have seen both forms, it seemed that whichever form people encountered first was the one they preferred, they were almost ‘loyal’ to it!

What immediately drew me to THE TIME BEFORE was the balance between 360° video and hand-drawn animation. Leo works within that unique Royal College of Art tradition, at the edge between childlike simplicity and total sophistication. It looks effortless, but it’s incredibly precise—especially when you’re animating at twenty frames per second. We created everything remotely, never sharing the same studio, yet the collaboration was astonishingly fluid. We built a dialogue where every detail—the movement, the texture, the light—served the emotional purpose of the film.

Michael Golembewski, Interactive Designer

Memory, Consciousness, and Childhood

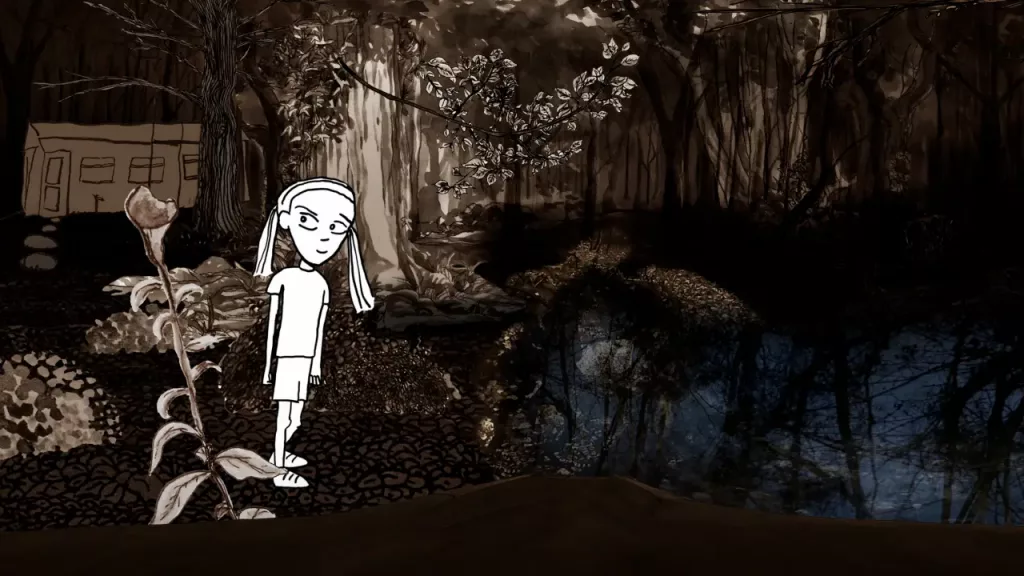

L. M.: At its heart, THE TIME BEFORE started out as a meditation on consciousness: how it arises through the constant interplay of memory and perception. I wanted to explore that through fiction, placing the viewer inside the mind of a boy navigating his earliest memories. The story follows Olly, a man caught between memories of waking life and dreams, who revisits the fantastical worlds his sister created to shield them from family strife. It’s a journey into the buried past that shaped who he is.

While writing, I realized how much nuance was needed to tell such a story from a child’s perspective. Some moments came directly from my subconscious: fragments of dreams I’d recorded on my phone every morning. The underwater scenes stemmed from my lifelong fascination with the world underwater and how otherworldly it can look. I’d been filming underwater for years using my Canon 5D and later a 360 camera, experimenting with light and movement and filming wherever I could: streams, lakes, rivers, caves, waves. Many of those sequences became part of the film, layered together as collages of videos to evoke Olly’s dreams.

The memories were depicted by raw, hand-drawn animations.

The Challenge of Hybrid Worlds

L. M.: One of the project’s challenges came from merging drawn elements with live-action 360° footage. We wanted everything to feel cohesive and emotionally believable.

One of the most fascinating challenges of the project was to make the relationship between drawn elements and live images coherent. The paradox is that 360° video, which is supposed to create depth, actually flattens the horizon, while the drawn elements truly exist in three-dimensional space. For instance, in the lake scene, we added a 3D foreground — tree trunks, a clearing — to recreate a believable horizon line, because it’s no longer about filming a bubble but about opening perspective. And underwater, we injected tiny floating particles into the field to give the illusion of a liquid volume of space in motion. These almost invisible details are what make the film perceptually credible.

Michael Golembewski, Interactive Designer

Between Film and VR, Fiction and Emotional Truth

L. M.: The piece was founded on the desire to share a strong narrative above all else. I wanted to maintain the emotional sensitivity of cinema while embracing the freedom and immersion of VR. Projects like WOLVES IN THE WALLS showed me that interactivity can remain narrative: that it can engage with emotion rather than distract from it.

Early on, I introduced the idea of an emotionally and physically violent father as a way to create conflict, but it was really a narrative shortcut. In reality, my father is a kind and gentle man. I thought I was just exploring consciousness, how the past shapes us, but over time, I came to understand that even if THE TIME BEFORE wasn’t autobiographical in a factual sense, it was profoundly personal on an emotional level. Through the process of making it, I realised I was confronting my own emotional stunting and the ways in which unremembered childhood experiences shape who we become. That discovery transformed both the meaning of the story and my relationship to it. My mother also passed away during production, which deepened my desire to explore memory: to understand what memories are made of: words, images, feelings and sounds. Using the intimate darkness of the headset I wanted to invite the audience to reflect on the shape of their own memories of their parents and what they will ultimately be left with.

In the film, I say, “It took me 25 years to realise I missed being able to cry.” That line reflects something I only came to understand through making this work. My emotional stuntedness came from a particular upbringing, but the wider issue, men struggling to express emotion, is everywhere. I think the bravest thing we can do is feel, and to communicate those feelings. When we lock our emotions away, we don’t just lose part of ourselves, we lose part of our connection to the people we love.

My hope is that THE TIME BEFORE encourages viewers to embrace vulnerability: to see that honest storytelling and emotional openness are not signs of weakness, but the foundation of genuine human connection.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.