We will be covering IDFA DocLab again this year to dig more into the immersive and the interactive field. As the first main event (since 2007) to be interested in the digital era of interactive storytelling, the IDFA festival presents 2 competitive line-ups (IDFA DocLab Competition for Digital Storytelling, IDFA DocLab Competition for Immersive Non-Fiction) as well as a thematic exhibition (DocLab Exhibition: Phenomenal Friction) and a full programme at IDFA Forum. We discussed everything with curator Caspar Sonnen.

Cover: Redemption (Redenção), by Mariana Luiza

KC: : I know nobody likes to define a genre or an area of work. But at IDFA it’s called New Media, there’s digital storytelling and an immersive section-it’s called many different things. So not that you want to put a name to it…

CS: I would love there to be a name.

KC: We have immersive, interactive, digital, XR. How would frame it?

CS: I think it’s so interesting to see… the most used one now is XR, but we don’t really define what it actually is. It’s kind of a good grouping of different things. And there’s people who say XR is MR and AR and VR. But does it include AI? There’s also interesting things happening there right now. So that’s also XR.

I remember when “XR” started emerging around 2015/2106. The term was new to many people, but a lot of people knew it. We did a Google trend search of XR, and it had this incredible spike. But after the event, one AI artist came to me and said, “Actually, do you know what that spike was? That was the launch of the iPhone XR.” But we all in the field were like, yeah, this is probably the new term.

I liked the term immersive. It’s just a lot of letters. I like XR because it’s quite short and undefined. And still tells us something.

KC: But do you feel like it indicates technological things, like in a digital sense? I feel like immersive can take more forms than XR can take.

CS: I agree with you that using immersive and interactive is nice, because you can have interactive theater, and that’s not necessarily the same as immersive theater. Or an interactive film is not the same as an interactive theater experience, like interactive dance is not the same as an interactive game. Using these things together, I think, is more useful than sticking this one term to define a moving target. If I’m honest, I don’t really know I can technically pinpoint the difference between VR, AR and MR. But if I’m really honest, I’m not sure that’s really leading me anywhere. Because I feel the technology keeps shifting, blurring the boundaries between the three of them. But I do make a distinction between an in-headset experience, and an experience that is site specific or not. I think XR solves a lot of problems and is a really useful term works for what we do.

In the end, who cares about technologies, but what kind of experience you can do with it.

KC: Many times you see work that theoretically is really interesting, but doesn’t move you or viscerally give you a reaction or an emotion. With XR, you run the risk of having the new innovation in technology drive a piece. Sometimes that loses the connection to the person because we’re so focused on the new technology, we’re letting the content or the feeling get lost. There are a lot of pieces in your program that are driven by technology, especially AI. Even your description alludes to technological efficiency and convenience. How do the works in your program manage to balance that kind of conceptual technology and innovation with new ideas and art?

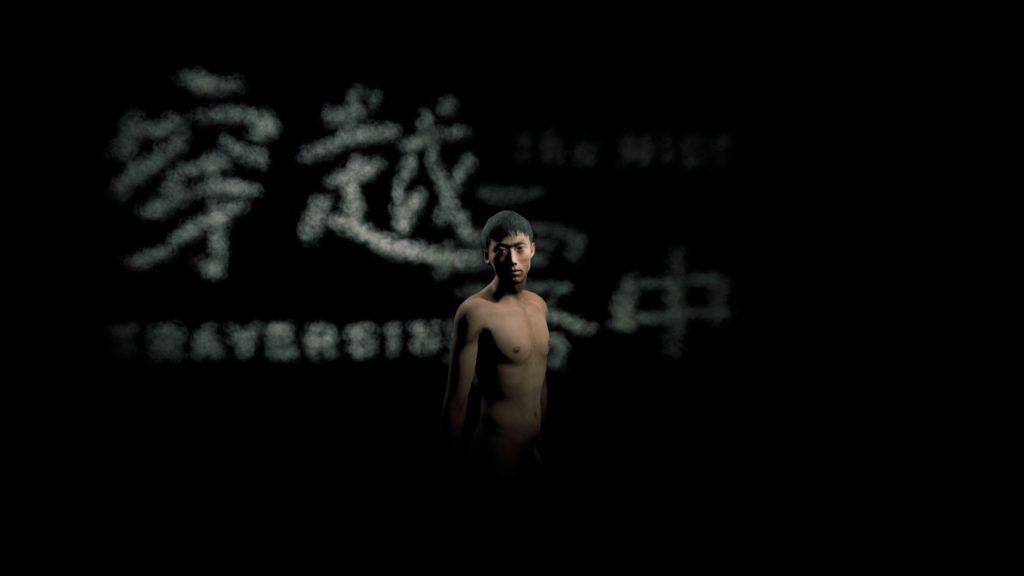

CS: I think you can be too technically obsessed. I definitely see this with certain artists in this field that are technically incredibly skilled…sometimes the tech is the first filter we see. That’s why it’s such a privilege as a festival to be able to see different audiences. For us, one of the great gifts of being part of a documentary festival is that we get audiences who are seeing VR for the first time, as well as a lot of people who’ve been with us for years and are core people in the field. To see the different responses to that really shows you that a piece like Traversing the Mist or Emperor are projects that all kinds of audiences respond to in the same way. And essentially, what moves you in an artwork is a great story. And it can also be your mind is blown by having not seen or experienced or felt something like this.

We have quite a few AI pieces this year that really play with things, and the great thing is they’re made by really strong artists exploring what AI can be. Some of these pieces are really on the forefront, and give us experiences that I never had before, I only knew were coming. William Quail’s Pyramid, for instance, is a great example of a long-term research project that we’ve been supporting for a while, trying to build an AI that can create a Verner Hertzog movie. This is not that film, but a piece that speaks to AI still requiring a lot of curating. We still need humans to say this is good and this is bad or this makes sense, this doesn’t. The artists created a work based on all the offcuts that aren’t making it to the movie because it doesn’t make sense, which to me sounds very interesting conceptually. But when we started seeing some of the first results of it, that was the moment that it moved us. That was the moment we felt excited to select it. The idea in and of itself, the technology in and of itself isn’t enough. It’s what does it do to you. Why is it meaningful? Why does it move me? It took me to a place that I hadn’t been yet with AI, to see how far it is getting. It took a step sideways, and made me reflect in a different way about what we’re doing here.

In Voice in my Head [commissioned by IDFA], Kyle McDonald and Lauren McCarthy have created definitely one of the most uncanny AI experiences at the festival. Have you ever wondered what it is like to have yourself be spoken to by yourself? It’s one of those examples where I think: what is the Pandora’s box here?

It’s interesting. Each year our R&D program has a different research question. When we started the R&D program five years ago, the initial question that MIT researched that year was ‘What are different forms of authorship? What does authorship mean when artists are co-creating with machines?’ And back then, the answer was mostly human, the machine doesn’t do that much. Five years later, we can see how that question then inspired different artists to explore.

This year, we’re presenting a full dome evening featuring the recreation of an existing VR work from 2018, Ahorse, that you are not able to see any more technically today. The artist started working with a planetarium to create a full dome version of this VR piece, but sadly, the artist passed away suddenly earlier this year. So it’s the posthumous premiere of that work. But it’s beautiful to see how it translates to a collective experience. It is also one of those pieces that really touches upon the topic of preservation, and the collective memory of our field. I mean, this is the 17th edition of DocLab. Many of the conversations that are happening today around AI, or were happening a few years ago around immersive, are conversations that were happening around interactive media and digital arts 17 years ago as well. And a lot of those works can no longer to be seen.

If we want to really push XR, we really need to start working and taking our collective memory more seriously. Because I don’t know a lot of art forms where you start creating without having seen a lot of masterpieces and classics. How often have we seen a project that promotes itself as ‘the first project that uses XYZ technology or creates XYZ’? And I’m thinking, ‘I don’t think you’ve done your homework because this reminds me of three other pieces that did that already.’ And actually, how important is it to be first? It’s usually more important to create a great experience than to create the first experience.

Climate, XR and the future of distribution

CS: In the program this year, we have an interactive installation that is very much fueled by climate protest, Offset: the Boiler Room. And there is the climate research that Landia Egal and Amaury Laburthe are doing around the project they presented last year, Okawari, where they are exploring the climate impact of the XR industry.

They’ve done things like compare different headsets, the power consumption and the rare minerals used in different headsets. But also on a wider scale…there’s a painful truth to the reality that extracting the minerals needed to create a phone or a VR headset or a laptop is killing us. What would be the carbon costs of everybody having a headset at home? We can’t afford that as a planet. They challenged this question. Should XR or the immersive as an art form be something consumed individually in our living rooms? Or should that be something that is a destination that we go to, because we don’t all need a headset at home? We now make things more social with MR and AR to solve the problem of the initial headset. Whereas interestingly enough, imagine if VR would be a destination?

It’s an interesting challenge that came out of that climate question. What if immersive is something that is a physical experience? It makes a lot more sense because it’s spatial, it is essentially physical. The social experience physically allows so much more potential, artistically, which is why we’ve always been exploring live events and different formats.

For instance, Traversing the Mist this year…

KC: I’m very interested to see how he takes it into a different direction, more interactive than just the observational, immersive piece.

CS: I had the same feeling. In the Mist [the artist’s previous piece] was such an amazing piece. And it’s the same artists, it’s a very similar topic. But it’s a different experience. I went into it thinking skeptically, or just curious how they done it, and came out of it with a completely different experience from In the Mist. And the difference is, who I was in that piece, where I was in that piece, and what that meant. I was moved by it. I think seeing both pieces gives you an opportunity to also really feel the power of a spatial medium, to feel what it means to have a social experience or not, to what it means to have a body or not in a in an experience. And it’s very rare that we get to compare, right?

KC: Is that one of the topics inspiring the R&D Summit this year?

CS: We’re working with MIT, and one of the questions they’re really looking into is embodiment, with a broad approach. There are different pieces in the program that really connected this. Projects like Close and Dance Permit (Denied) are two projects created by and with immersive dancers. Both projects really deal with the physical body, in reality and in a spatial context. There are projects really exploring using motion capture, sometimes in a more technical level, sometimes in a more content level. Traversing the Mist is an example of really showing you what it means to have or not have a body in an experience. Are you alone with your body or are there other bodies there? How does that change your experience? Some of projects using AI, I think, are also shedding a radical and interesting new light on what it means to have an embodied experience, where part of the experience is automated and affects the way that you experience it.

KC: You awarded a Spotlight Award to Natasha Khanyola from Kenya. What is the background of that award?

CS: This is a thing that happens IDFA-wide, where we work with other festivals in other regions to give a Spotlight Award. In this case, it was in collaboration with the Fak’ugesi festival and our Digital Lab Africa. We work together with them to select one artist out of the different lab participants that can come and experience the festival. Because, if you want to create something, you need to see works but also need to meet people. It’s important to know what kind of festivals and people are out there. So it’s a little thing we do, but for the people it’s quite unique. And for us, it’s also great because outside of the award, through that connection, we also discovered Phantom, which is an amazing piece that won an award at Fak’ugesi and is now part of our digital storytelling competition.

It shows these connections are important. We’re living in a time where we can see different regions are not disconnected from each other. It feels like the amount of interaction we’ve had with each other has been reduced a lot over the pandemic, but also I think for a much longer period everybody has been diving into their bubbles and their own belief systems. That’s where our theme came from – “Phenomenal friction” – where it’s hard to have any form of interaction without actually touching each other, without actually having a form of friction, as awkward and tricky as that might be sometimes. More connection is what we need, not less.

The program this year is a beautiful reflection of that. We have one of the more diverse programs this year, in terms of regions and artists represented. One of the biggest compliments that we’ve been getting from some of our favorite artists and friends in the field is that they’re excited to come because there’s a lot of people they’ve never heard of.

It’s wonderful to see some of these amazing people emerge. That in the end is more important than how we define XR. I think it’s great having new, exciting artists emerge within this field, and having their work get seen, not just this year, but in the long run. I think that’s why we’re here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.