A technical in-depth look at the documentary Reeducated, winner of the Special Jury Recognition for Immersive Journalism award at SXSW Online 2021

During SXSW Online 2021, we fell in love with Reeducated, a brilliant example of immersive journalism that opened our eyes and hearts to the plight of people in Xinjiang’s “re-education” camps.

Reeducated is a documentary by The New Yorker, based on Ben Mauk’s reporting (go follow his blog, it’s absolutely impactful) and directed by Sam Wolson. We spoke with him for this interview where he told us about the origins of the project, the creative process, and how VR has influenced his life and journalism as we know it.

This film left a lasting impression on us. The need to help people become aware of the situation it told prompted us to want to know more about how Reeducated was built, technically speaking.

That’s why we asked Jon Bernson, sound designer and composer, artist Matt Huynh and Nicholas Rubin, lead animator and technical supervisor of the piece with its company Dirt Empire, to tell us more about how they worked at Reeducated and the main challenges they had to face.

- Read our interview to Sam Wolson

- Visit the interactive New Yorker feature “Inside Xinjiang’s Prison State.”

- Watch Reeducated on YouTube

- Read Ben Mauk’s insight on the piece

A journey in the sounds and music of Reeducated (Jon Bernson)

On creating the musical score

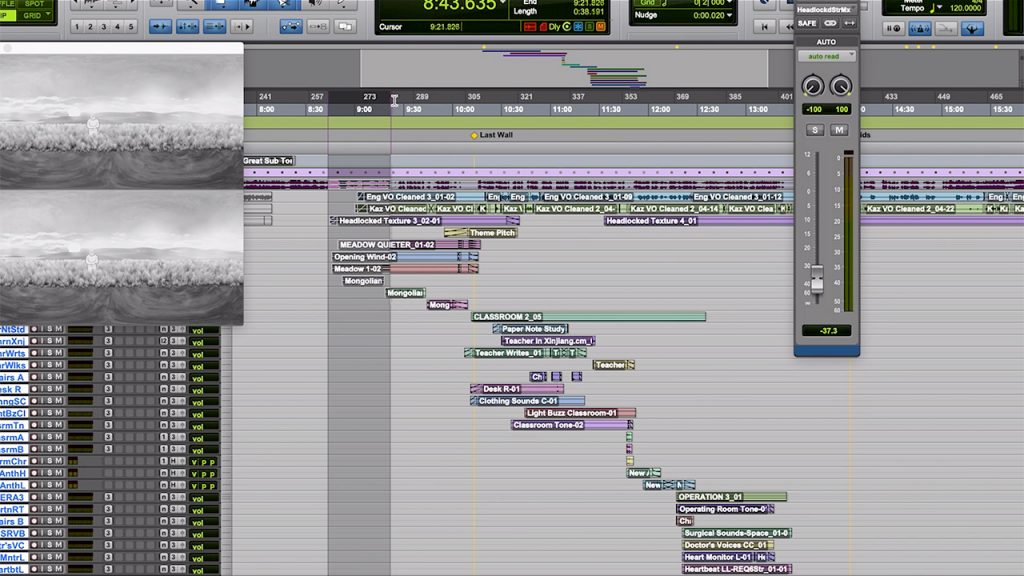

JON BERNSON – To create the musical tones for the score, I used a sampler to combine Kazakh/Mongolian instruments with synth patches, which could then be played on a MIDI keyboard as I watched the scenes. We wanted to use subtle scoring to convey subliminal shifts in mood; there’s no melodrama to be found. The voiceover was honest and clear. We wanted each word to land.

On creating the sound design

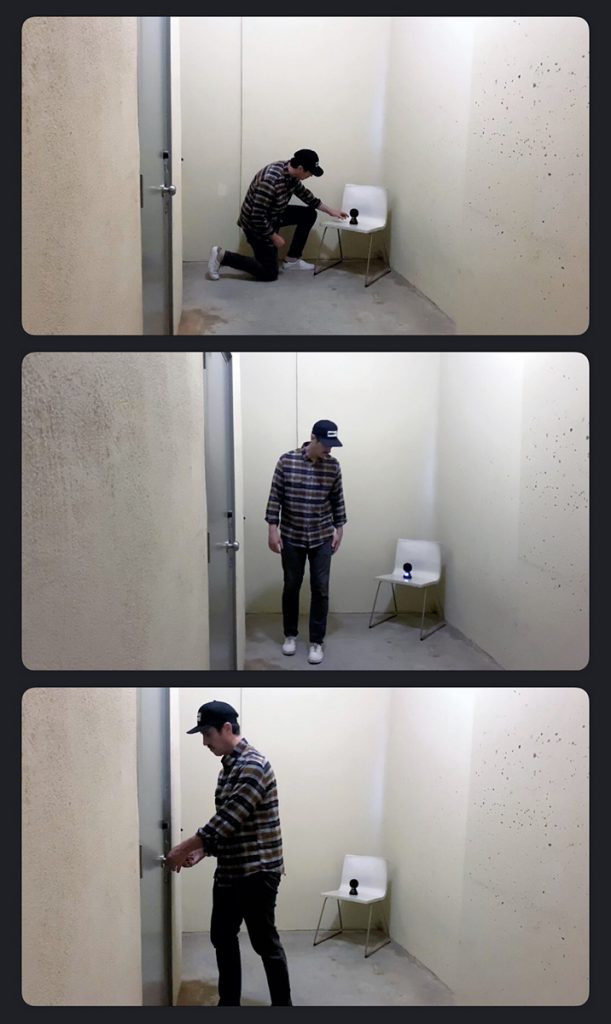

J. B. – Given that no one can get inside the camps, all the sounds had to be recorded in areas that might have similar acoustics. This is an imaginative process as well as a technical one. To capture the feeling of the yard scene, I drove out to Treasure Island, which is a former nuclear-training site for the military in San Francisco. There’s a lot of open concrete and dozens of abandoned industrial buildings that proved to be great for field recording. I figured the radioactivity might serve as a stand-in for the oppressive conditions in the camps.

On personal breakthroughs and challenges

J. B. – Ambisonic audio has been around since the 70’s, but wasn’t used much until VR came along because it requires 360 degree audio that is responsive to the user’s movements. This particular application of ambisonic technology is still in its infancy, so there are a lot of bugs and counterintuitive problems that can make even the most basic scenarios glitchy and complicated. At times, it was maddening.

As with the animation, everything sonic had to be created based on descriptions of each space and what it might sound like, or in the case of the score, feel like. In my mind, the challenge and end goal in every scene was when the picture and audio coalesced and the experience in the headset felt natural, as if it had been captured live. Considering the fact that this crew lives in different corners of the world, the chemistry we developed in bringing these immersive environments to life is an accomplishment I’m not sure any of us fully understand.

Immersed in the art of Reeducated (Matt Huynh)

On creating artwork in VR

MATT HUYNH – My most obvious contribution to Reeducated was the hand drawn ink and brush artwork.

The warmth and fallibility of a human hand in every asset and frame of animation is something I hadn’t seen before in VR, for good reason! It’s not the most efficient or easiest way to work in VR, but in such a heavy story about systematic persecution with almost no film or photography of our protagonists, it was most important to me to constantly have a human touch.

Capturing the soul of a film through artistic choices

M. H. – My animation choices were driven by two distinctive characteristics of the film. First, Reeducated places viewers in spaces that have never before been seen, so I wanted to encourage and allow active discovery by the audience. The audience is moved along a string of enclosed environments, even more so than character-driven actions or a chronological timeline.

Secondly, we are guided through the film by the memories of three former detainees, so the animation needed to have a sense of drifting and suspension that has the impression of recall.

On the use of dioramas for motion

Rather than the language of a traditional animated film in constant motion within a frame, the immersion of VR meant I had to be deliberate with how motion was used to direct the attention of a viewer. Instead of constant motion, I arrived at dioramas with selective motion along the spectrum of perfectly still illustrations, boils, loops and unique actions.

A boil directs the viewer primarily to a character, pulsing with their own thoughts and will, but a boil is a quick read because there’s no new information. A loop draws attention primarily to an action like singing, reading or sleeping. If an action is too idiosyncratic, the conceit of the dreamy pace of remembrance is broken. A distinct action places the viewer in a singular moment and pace of life that too closely approximates the novelty of experiences outside the headset.

We risk waking the viewer from the suspension of time we hope to create to explore a fabricated environment that the viewer’s transported into. And of course, all these rules were ready to be broken for effect. For instance, an inanimate object may be given animation to emphasise the regime’s power in a setting where everyone else is stripped of autonomy and too afraid to move.

The challenges of this medium

This was my first time telling a story in 360 VR, a challenge I embraced for the opportunity to work with a beginner’s mind. Working to the medium’s strengths meant working against my initial instincts and habits, but my guiding principle in a medium that can easily overwhelm with its expansive possibilities and media was to be directed by the story and our storytellers first.

The technical challenges of animating Reeducated (Nicholas Rubin, Dirt Empire)

On the development of a sophisticated stereoscopic VR film

NICHOLAS RUBIN – Dirt Empire was responsible for several key aspects of the production for Reeducated. We were brought on at the relative beginning of the project when the only materials that existed were a few panoramic concept drawings of the cell and a full storyboard drawn in rectangular 16 by 9 format.

I don’t think Matt Huynh, Ben Mauk and Sam Wolson, who were collaborating on the creative development, or myself as lead animator anticipated quite how much room there would be to grow into the final sophisticated stereoscopic VR film we wanted to make.

Primarily we built all of the scenes in Cinema 4D with Octane Render and composited the final 2D animation in Adobe After Effects. Digital animation production began at the exact same time as Matt was working on the drawings. We began building the scenes in tandem with temporary assets so that we could develop the overall feeling of each scene. There were a few top level aesthetic conceits we had to work with in laying out the environments.

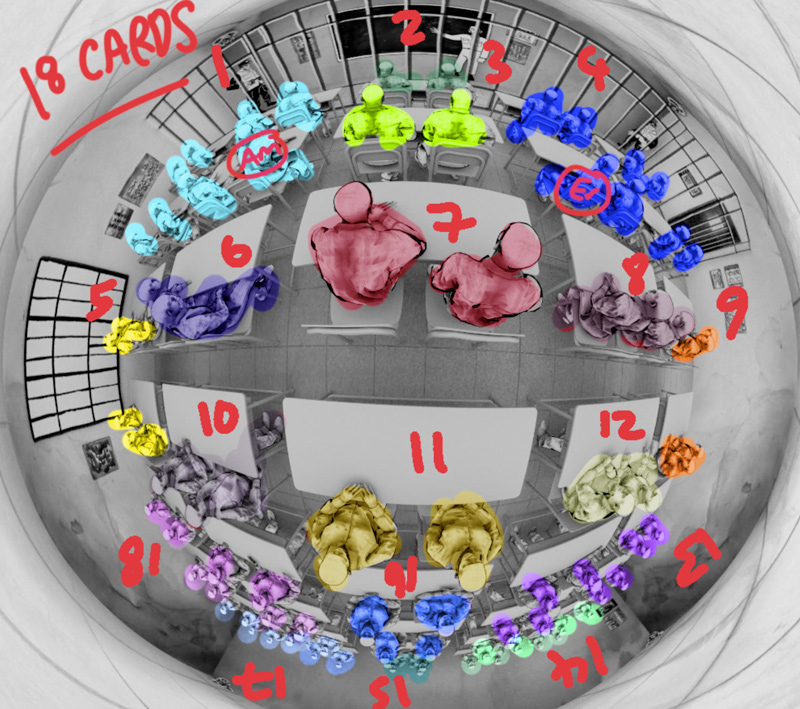

For all the scenes that the three detainees had experienced together with corroborated accounts, Matt had drawn overhead “maps” of the rooms. We built those in 3D and lit with bright hot lighting since they were more forensic in nature. All scenes that corresponded to more internal, emotional spaces were designed to be film noir and abstract. This gave us a visual logic for seamless transitions to avoid any hard cuts.

Animation production challenges for Reeducated

N. R. – One of the most difficult aspects of the animation production was arranging all of the flat hand drawn animated characters in each scene.

In total there were several thousand drawings. Each character had anywhere from 4 to 24 frames of frame-by frame animation to place in scene. Since the VR camera spherically distorts things closer to the camera and many of the sets are very intimate spaces, we had to use posed 3D mannequins in dramatic gestures and render flat versions of them with camera distortion for Matt to use as drawn reference.

This was especially difficult in scenes where characters moved past the camera. Since many of the characters didn’t have active gestural performances – but we still needed them to feel alive – we decided to render them with “boils”, which essentially is a retracing of each pose. Some scenes had 30 to 100 characters so we had to stagger them chronologically and in a way that their vibe didn’t feel too mechanical or repetitive. This was just one of the huge challenges inherent in the two-dimensional composite of the project.

On choreographing levels and coordinating efforts

N. R. – As a result of working in 3D Stereoscopic, doing anything photo-realistic or cinematic (like volumetric lighting, soft focus or light rays) was a huge challenge, since the illusion – if done poorly – would create eye strain and break the Z-depth.

Since we had so many interdependent layers we couldn’t render this straight out of Cinema 4d and Octane as one would in a normal 3D pipeline. So many of these effects we had to recreate in 2D with 3D layers.

There was a tremendous amount of delicately choreographed timing between layers in after effects as a result of all the character layers, puzzle mattes and animated lighting transitions. So even after the primary assets had been drawn and painted by Matt, we continued to render and composite animation for another 3-4 months.

We were essentially building the scenes – lighting, editing and designing – all at the same time and working in tandem with rough cut edits from Sam to build the piece organically from the very beginning.

This allowed for creative and aesthetic exploration almost the entire time but it is not the way a normal CG animation is produced and is incredibly time consuming. It really wasn’t until the 11th month as Jonathan Bernson’s incredible ambisonic sound design was finalized that all the pieces fell into place and we realized that we had succeeded despite the long production schedule.

Luckily, despite the very long production schedule of almost 1 year, our very dedicated team of 5 VFX artists put in as much time and effort to make the piece as good as it needed to be to give the subject matter the platform it deserved.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.