He Fucked the Girl Out of Me premiered at IDFA in 2022. The video game piece explores sex work and trauma by recreating moments for the player to go through. I talked to the creator Taylor McCue on advocacy, shame and straddling the line between the gaming and documentary worlds.

Trauma, Social Impact & Gaming

Karen Cirillo – Your piece addresses a serious issue of trauma and sex work, and for me, playing the game itself is the social impact. You can tell when people are trying to send a message as an advocacy tool. A lot of that kind of content comes across as propaganda, even if it’s good. But I never get that feeling from your piece. I feel like the simplicity of the technology allowed me to focus more on the experience, which made me think about the issue in a different way. To me that always speaks so much louder than someone who’s trying to sell me on something.

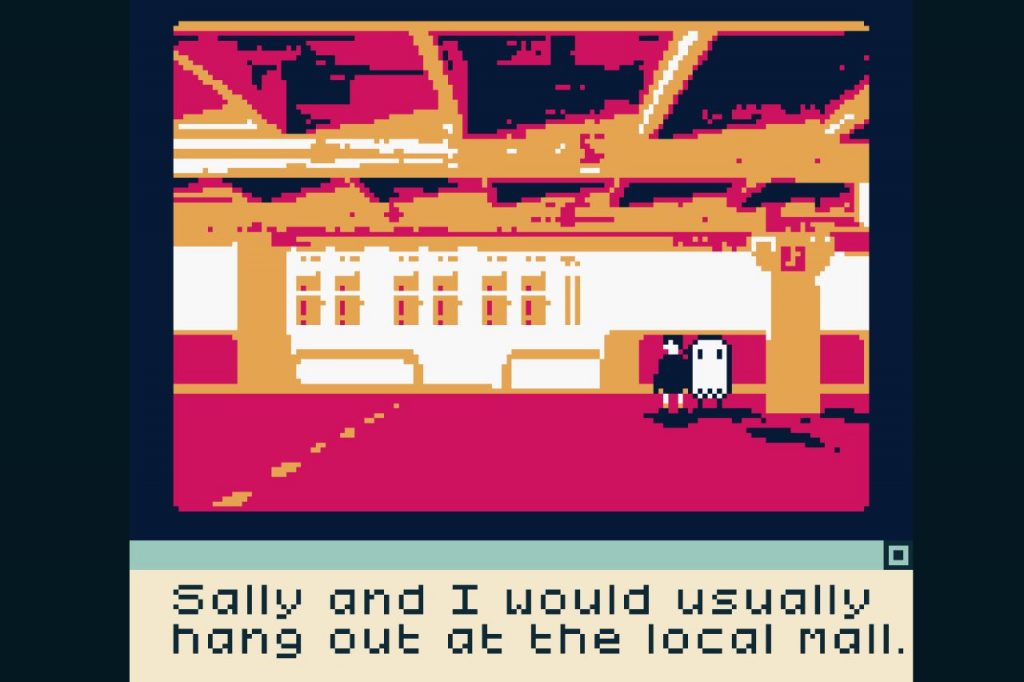

Taylor McCue: It is actually really old technology, because it’s like 1989 computer programming. It’s actually a Nintendo Gameboy. That’s why all the technical limitations were like… I was limited to four colors on screen at once. The reason I chose that format is, frankly, writing about that shit was really upsetting. I couldn’t do a more complicated computer programming thing. I was just like, ‘I need something I can do while crying really hard.’ An ancient Gameboy game was easiest to do.

T. M. – And I’m gonna be honest, I did actually use propaganda techniques in designing my game, because I was afraid of being rejected. I threw every single technique I could into making an argument on why I should be accepted as a human being [for the sex work stuff], because I knew fundamentally what I was asking for was a big ask.

T. M. – So I use cognitive priming at the beginning of the game. The first thing you see was a headless ghost masturbating. And the reason why I set that up was first to prime people to not view it as like porn, but as like, disorienting. It was the goal of first priming people to think that sex is uncomfortable and disturbing. And then the next step was setting up that sex scene so that everybody who would be offended by sex would immediately leave and walk away, so that I could remove anybody who would harass me quickly and efficiently, because I couldn’t control who would see it. And then I immediately set up the person being rejected (by the game) and told that they’re disgusting. Because I had to put them in that sense of being rejected in order to raise their empathy for me, and reduce the odds that they’d reject me later on. I used a lot of cognitive psychology techniques.

Using interactive display to discuss social acceptance

K. C. – Do you feel that you were using those techniques in a way to be an activist or was it more about using those techniques to create a safe space for your own experience?

T. M. – Basically, I had a lot of deep shame and the only way to get over shame is by telling it. But I was worried that so many people would dogpile me on the internet when I already felt so bad. So I basically threw every single cognitive technique and game design technique that I could at the viewer to be like, “Please don’t hate me.” That’s not activism or social justice. That’s just an appeal for acceptance. I think it’s also sort of brainwashing and I feel guilty about that. But it’s really hard to come out and say those things. So I really basically just designed a machine to inflict trauma on people in a weird way, so that they would understand rejection, understand shame, and then accept me. It didn’t work 100% of the time, but it worked enough that, like, most people would accept me.

T. M. – I really wish I could say I was doing social outreach or advocacy work when I was making the game, but it was really just to get over my own drama.

K. C. – I get the sense that you probably feel more comfortable behind the computer creating something as the voice instead of the actual talking voice.

T. M. – When I actually go to events in person, which I’ve only done a few times, I basically just turn into a used car salesman. “Here, you can play this game. It runs on your cell phone. Don’t wait in line, load it on your cell phone today. This baby has so much trauma.” I answer the same five questions. And it doesn’t feel like me. But sometimes people will ask deeper questions and then I’m like, ‘Oh, shit.’ It’s hard to explain.

Between arty events and gaming fairs

K. C. – So now you’re showing it at artsy documentary and festival events, and then also gaming conferences and events. Wow, that must be really … similar or very, very different?

T. M. – Documentary people tend to be more intellectual and have more media literacy. They also tend to be more liberal. Gaming people tend to be lower media literacy, and they don’t get stuff all the time. They also tend to have two groups, which are like leftist groups. And then there’s also a group – Imagine there are boys who are like ‘video games are my personal paradise, no girls allowed’. But then they grow up into men. And the only women that they want at the events are like booth babes. And when there’s anything that’s not white and male, and it’s not sexy…It pisses them off, because they feel their personal space is being invaded and made unsafe. Or it is something for them to mock. And so documentary festivals don’t have that sense of ‘this is my private space’. Like they usually want a lot of differences.

K. C. – Gaming in a lot of ways is, as you said, a personal thing. It’s your space, most times at home. But in the festivals, it’s just in a room and other people can watch you playing the game, which I think is also a very different experience. Did you think about that at all? Would you rather it be played in a room with a curtain? Did you even have any intention about what it would look like after it left your fingers?

T. M. – I really didn’t think it would be played by as many people as it has been really. My last game was so universally hated that an alt right person commented to me that it was amazing that I got both right wing and left wing people to want to break my hand. So I was expecting a little bit of hate, and then to be utterly forgotten. And instead, I didn’t get that. It wasn’t really designed for people to be watching it, or like in the space.

K. C. – Does that make you uncomfortable?

T. M. – No, I’m very, very grateful. When you have a lot of shame, getting a ton of nice comments from people on the internet helps, but doesn’t really help. Whereas getting to go to Amsterdam – it was a chance to get to go someplace else where I felt safe. And then have a bunch of people be like, “I accept you.” And get to be in an environment where there were sex workers around. So I wasn’t the only person with that experience. I could walk around the street and see a sex workplace and be like, ‘holy shit, it’s just normal’. Getting to experience that forced me to get out of my room and from living in shame. And it actually gave me a lot more confidence than the internet ever could have.

T. M. – I don’t think I would have ever sought that out. I didn’t actually submit to any film festivals originally. I released the game on Steam (link). And then IDFA messaged me and said ‘we want to have you be part of this’. And I was like, these people are a bunch of 4chan fuckers and I can totally see right through them. I’m sure they’d be really proud to hear. I said, ‘Okay, bro. That’s great. Like, I’m sure you want to invite me to Amsterdam. I’m sure you loved my game.’ Then I ignored them. And they came back to me – ‘please fill out the application’. And again, ‘seriously, just fill it out’. Like for real? They accepted me and then they were legit. Through that I got invited to other festivals that played it at IDFA. And then said ‘we want it to have this here. And then I got in. And it was just like I stumbled into the documentary world. I wanted to be a game developer. It’s like being told, ‘You’re not a baker, you’re a tire maker. And this thing you call a donut is an amazing tire.’ And I guess the donut can be a tire, and I can see the logic completely. And I’m glad I stumbled into an alien world. It’s much nicer than the gaming world. And I’d like to participate in it more. [The game] wasn’t designed in that way. But I probably will apply in the future things. And I feel like I’m operating on a weird gamer nerd logic. I get the game dev people more and the game world more. But I like the documentary world because the game world’s pretty hateful.

It’s about choices

T. M. – Can I ask you a quick question? In the end, did you choose to say that you loved or didn’t love Sally [at the end]?

K. C. – I loved.

T. M. – Interesting, why?

K. C. – I tended to choose the first option, the default, unless I particularly wanted to not choose the obvious answer. Sometimes in those scenarios, the way that they’ve designed the game – it answers obviously what you chose, but then somehow works a version of the other one into it. So you’re kind of like, Oh, I bet if I chose the other one, this would have been the answer. I kind of thought that that would happen and it didn’t. So I never got to know the other answer. I’ll have to play it all over again because there are a lot of scenarios where there are choices.

T. M. – Some of them were fake outs. Some of them have elaborate threads. Some of them don’t. The Sally one did have two different things.

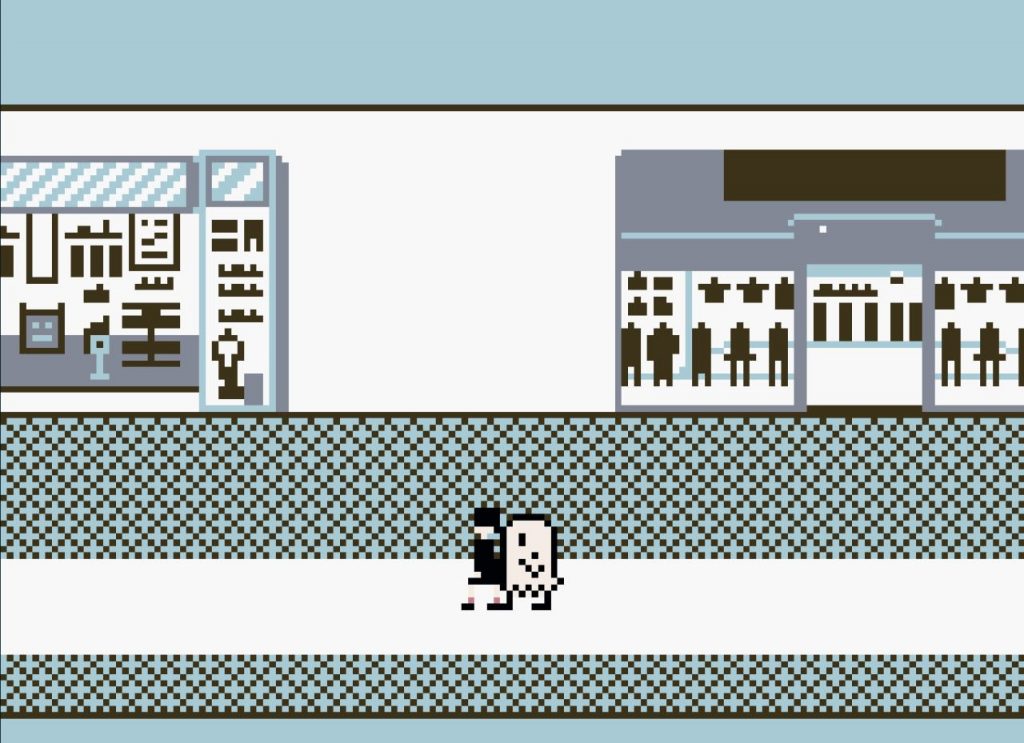

K. C. – You also have several parts where the player needs to experience something themselves before they can move on to the next scene – like in the food court.

T. M. – I wished I’d done [the food court scene] a little bit differently now. Because I didn’t really convey the real issue of somebody getting more and more uncomfortable as you take more and more.

K. C. – That totally came across. The thing is that the pace of the game makes you really feel the moment, in a way that I feel like a film experience can’t. It was the food court moment, where I thought I was doing it wrong but then I understood that this is your point. I completely got the point of feeling the uncomfortableness of going around in circles.

T. M. – If I were doing it today I would have had the food court person’s expressions go from like ‘Welcome. Please take a sample’ to gradually become more and more uncomfortable, forcing the player to make that person more uncomfortable until they say no.

K. C. – It’s very hard to make work about yourself. And it’s very hard to talk about work if it’s about yourself in any context, evidence, especially when it’s something that’s so personal and traumatizing. So I thank you for not traumatizing me. Because I didn’t feel that way. And I thank you for making it.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.