Koncept VR, a premier production company headquartered in New York, is renowned for its expertise in crafting immersive 360-degree films and cutting-edge XR content. Among its recent projects are notable 360 documentaries such as MLK CONVERGENCE, OMAHA BEACH, and THE SIEGE OF BASTOGNE. Led by the accomplished researcher, director, and screenwriter, Uli Futschik, alongside DP and producer Joergen Geerds, the team completed TUSKEGEE AIRMEN last November. This groundbreaking film marks Koncept VR’s third collaboration with the WWII Foundation in Rhode Island and its founder, Tim Gray. Offering a fresh perspective, TUSKEGEE AIRMEN illuminates the extraordinary achievements of Black American airmen who defied conventions and reshaped history during the tumultuous era of the Second World War.

TUSKEGEE AIRMEN : an inspiring story of perseverance

Uli Futschik – The Tuskegee Airmen were the first black American military pilots in World War II. The country was still in the throes of segregation at the end of the 1930s and the beginning of the 40s, with Jim Crow laws prevalent especially in the southern states. When the army started to build up their numbers in anticipation of entering the war, the only positions available for African Americans were support staff and menial labor. However, early civil-rights activists were pushing for more diversity and inclusion. The war in Europe provided the opportunity for that.

Joergen Geerds – TUSKEGEE AIRMEN is about the 332nd Fighter Group, who were under the leadership of Benjamin O. Davis Jr. (the only black student at Westpoint from 1932 to 1936 when he graduated ). We’re telling the stories of pilots, but also air traffic controllers, airplane mechanics, nurses, surgeons and administrative personnel. Because they trained at a newly established airbase in the small town of Tuskegee, Alabama, the term “Tuskegee Airmen” has been used to describe these men and women since the 1950s.

U. F. – We did extensive research before we started filming. There was a lot of resistance to allow African Americans to train as military pilots. But President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave into the pressure from black newspapers and groups such as the NAACP and an airbase for black pilots was established at Tuskegee, in the Southern United States where segregation was particularly grim. Trainees from the South helped those from the North to navigate this environment. This happened before the attack on Pearl Harbor; the United States was not yet engaged in the war. However, once trained the black pilots were not deployed like their white counterparts because the army didn’t know what to do with them. NO white commander wanted to take a black fighter squadron. Eventually they were deployed to Africa and their white commander sent pretty negative reports back to Washington trying to get them sent back home. Fortunately, the intervention of Colonel Benjamin O. Davis Jr. allowed the fighter squadrons to stay in combat. Their base moved from Africa to Italy, where they were flying escort missions for bomber squadrons – which are the missions they are most famous for.

J. G. – Losses over Germany were heavy for the American bombers, facing a very aggressive and efficient German Luftwaffe. This is where the Tusgekee Airmen came to shine, as they protected the bomber crews better than other escort fighter groups. During that time the tails of their planes were painted red to make it easier to identify them, earning them the nickname Red Tails (the story was also adapted into a film by producer George Lucas, see an interview with director Anthony Hemingway).

U. F. – The end of the war was frustrating for the Tuskegee Airmen as they returned to the still segregated United States. But the changes they had initiated were slowly taking place. In 1948 President Truman issued an executive order to end segregation in the military. The Air Force, founded in 1947, was the first arm of the military to fully desegregate and black personnel was fully integrated. This was the beginning of real social change. Despite these and other successes, the stories of these brave men and women were forgotten after the war. Our goal with this VR documentary, TUSKEGEE AIRMEN, is that more people learn about them and to especially reach younger generations through this technology.

Filming the air: re-enacting the battles of WW II in 360

U. F. – One element I really wanted to include in the documentary was the signature airplane, the Mustang P51, flown by the pilots while they were based in Ramitelli, Italy. These planes presented a form of freedom for the pilots that they didn’t experience in their regular life. Research led us to the Commemorative Air Force, a non-profit organization dedicated to preserving historic airplanes, and their restored P51. We hired the P51 and the dedicated CAF pilot for a day to shoot several aerial sequences. We set up our camera inside of the Mustang P51 cockpit, as well as on the wings and the tail outside. This may very well have been the first flight in virtual reality on such a historical aircraft.

J. G. – The effect of virtual reality on documentaries is powerful, because you can really capture the viewer’s attention. And you put them into context immediately. It makes history less abstract compared to traditional formats. Obviously, with a project like TUSGEKEE AIRMEN, as with our other projects, we try to film on original historical sites as often as possible. The viewer immediately and instinctively understands a lot of things: the locations, the relationship of history with reality in this place and so many related things.

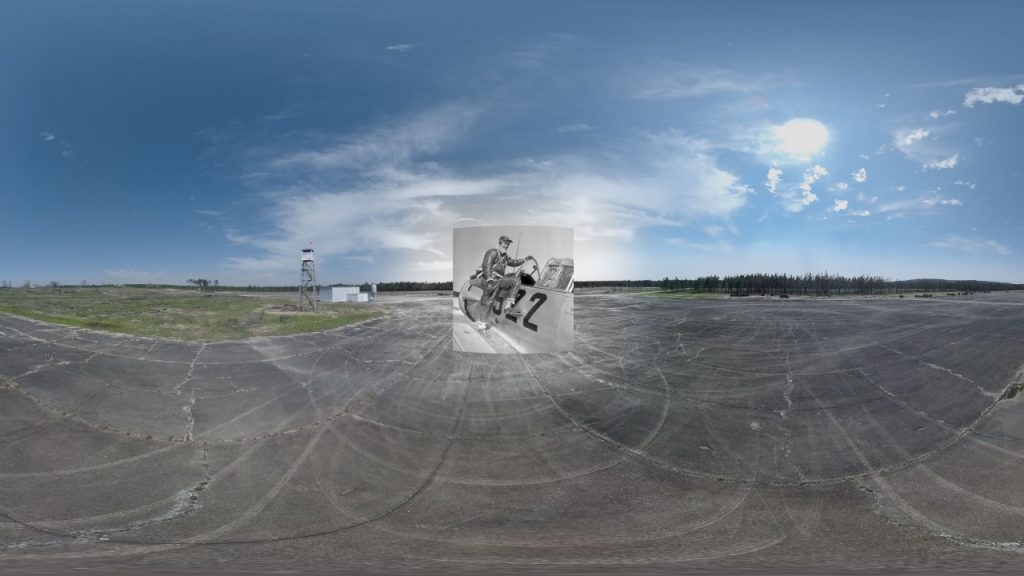

J. G. – As we did with our two previous two projects for the WWII Foundation, we merged archival photos and films with the filmed 360 scenes. We superimposed archival video on present-day locations and tracked it through the scene. We invented the “reverse Ken Burns effect”, so to speak, to be able to use 2D archives in a 360 environment. The idea is to match the archival footage to a proper location in a 360 scene where the viewer is free to look wherever they wish. Finally, Italian artist Chiara Masiero Sgrinzatto helped us illustrate some of the missing parts where no archival footage was available.

U. F. – With all this in mind, we had to make a number of directorial choices. Despite our desire to tell the whole story, we were unable to shoot certain parts on location (notably North Africa) for budgetary and scheduling reasons. This is where Chiara’s contribution was invaluable. In fact, she had already worked with us on previous projects that were probably even more complex (with lots of extras or vehicles).

Teaching the next generation

U. F. – We design our projects to be seen as widely as possible. The World War II Foundation is working on programs to bring VR headsets into schools or bring students to their museum, the International Museum of World War II, where they have a VR space with several headsets. Educating new audiences about World War II is vital and VR is a terrific tool for that.. Because not everyone is lucky enough to be able to visit the beaches of Normandy or the Italian town of Ramitelli!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.