Awarded with the Grand JURY Prize for Best VR Work at Venezia78, GOLIATH: PLAYING WITH REALITY is a VR experience that uses all the narrative tools VR can offer to tackle a difficult subject like schizophrenia. We talked about it back in 2019, when it was first conceived. Now we’re back to tell you more about it and the road it has travelled over the past two difficult years.

Two years ago… before the release of DUNE, before Covid, before festivals you could attend online even if you lived on the opposite side of the world, I was at a Biennale College VR event in Venice and for the first time I came across a piece that I would hear a lot about in the years to come. It was called, at the time, just GOLIATH.

It was still an idea then, something that directors Barry Gene Murphy and May Abdalla were developing and that caught my attention because of the way it was narrated by them and the subject matter it would deal with, schizophrenia.

Jump to six months later and this article is published on XRMust: a first interview in which Barry and May told us about their idea, how it came about, how it is progressing.

Another jump, this time to September 2021: GOLIATH: PLAYING WITH REALITY, in the lineup of the 78th Venice Film Festival, wins the Grand JURY Prize for Best VR Work.

GOLIATH: PLAYING WITH REALITY tells the true story of a man diagnosed with schizophrenia who, after several difficult years spent alone, finds solace and respite in the multiplayer gaming online community.

The recognition at Venice not only rewards the choice of dealing with a theme that is difficult to present even using the best artistic means. It also highlights the ability of the directors and the team that worked on GOLIATH: PLAYING WITH REALITY to tackle it using everything that VR can offer. Such as interactivity, used not just for the sake of interactivity but to push the narrative forward. To cite one example, when you’re in the Arcade (the beautiful 90s vibes of that scene!), the videogame you play is a classic 90s videogame – a race against time and lots of rewards to pick up along the way – but the “Super-mushrooms” you get are the drugs Goliath has taken to deal with his disconnect with reality, in a narrative escamotage I found particularly effective.

Another feature used effectively in GOLIATH: PLAYING WITH REALITY is sound… or rather: voice.

I’m not just talking about Tilda Swinton who, in herself, would make anyone love a VR piece, divine being that she is. I’m talking about a moment that has been mentioned in almost every review of GOLIATH found online, namely the recording of your voice saying your name at the beginning of the experience that returns later in a haunting moment that really impacts your perception of what a mental problem like that might feel like.

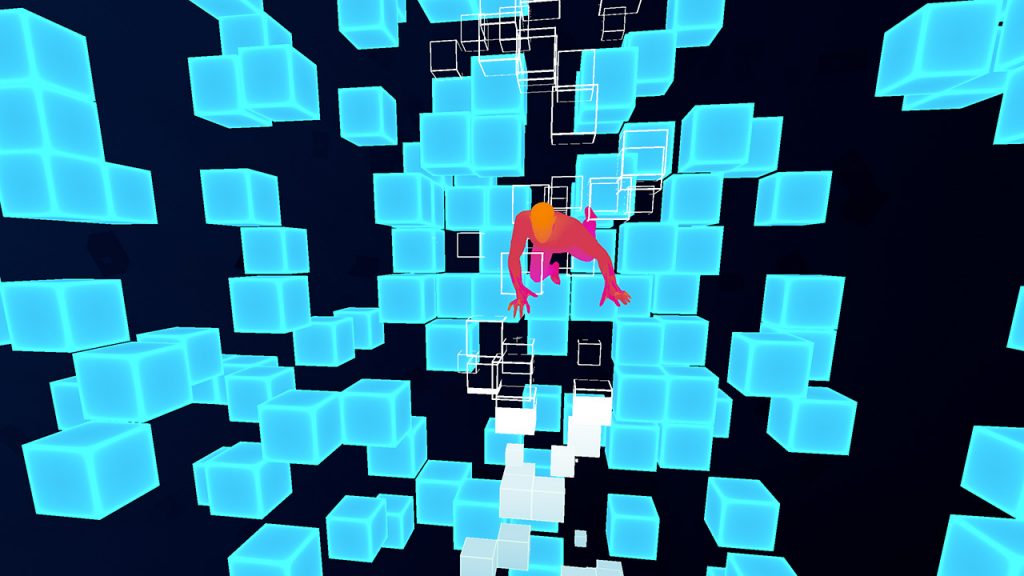

Sure, it can be hard to form an emotional connection with the character of Goliath himself – which I think says a lot about how difficult people find it to connect with those suffering from these kinds of mental issues – but it’s certainly appreciable how this heavy subject matter is somehow made easier to deal with and understand by the game-like approach this work takes in some scenes and the vividly colored visual choices.

We contacted Barry Gene Murphy and May Abdalla, directors of the piece, for an update on our previous article “Feel the narrative in your skin” and here’s what we discussed.

Back to GOLIATH

AGNESE – When we met, in 2019, you had just started working on GOLIATH. 2 years later, and not only was the work brilliantly finished; it also won the Grand Jury Price for Best VR Work at the Venice Film Festival! What has happened in these two years in relation to GOLIATH?

BARRY GENE MURPHY – The past 2 years have been watching GOLIATH grow from an aspiration to a fully fledged sublime form. When we were giving our first elevator pitches we had imagined a rough around the edges arty theatrical piece that we would have finished in a few months.

But as the idea grew and funders came on board to support, the ambition of the project grew. We got production funding just as lockdown hit and since then everything on our side has been GOLIATH-focussed, right up till launch in September this year. It was an extremely intensive production. We gave everything we had to it.

A. – How did it feel to win the award at the 78. Venice Film Festival?

B. G. M. – Having the recognition from Venice Film Festival has given GOLIATH that powerful boost to push it into the minds of the public and give it the extra visibility to find a wider audience. The respect for the award is amazing, everyone has been so supportive and happy for the project receiving such an esteemed embrace. All the crew were so jubilant and buoyed by it, along with Jon. It’s early days but what a beautiful start to GOLIATH’s launch!

GOLIATH’s development: from prototype to the 78. Venice Film Festival

A. – When creating a work like this, a lot can change from its initial conception to what actually comes to life in the end. What were the main changes that GOLIATH encountered during this development?

B. G. M. – GOLIATH had many versions: the pitch, the prototype, the vertical slice, the alpha, beta, then finally release candidate. Initially the pitch version was developed at the Biennale College VR residency. We fleshed out three scenes, and stripped them back and rebuilt them at the residency through the workshops. We had a rough sense of the aesthetic and space which was aiming to be like a recollection of memories, an internalised space in a mind. We imagined it would be volumetric photography mixed with cgi animation for the games elements mixed with GOLIATH’s audio story. We hadn’t yet interviewed Jon so could only guess at what would be said.

The Prototype

B. G. M. – When we received the Creative XR grant, we began the prototype along these lines. It started out on a self imposed residency on the Island of Inish Turk, myself, May (Abdalla, co-director, writer & executive producer of GOLIATH) and Mike (Golembewski, interactive design & development lead). Trying to figure out what we were going to do. We had our first interviews with Jon as a sound bed.

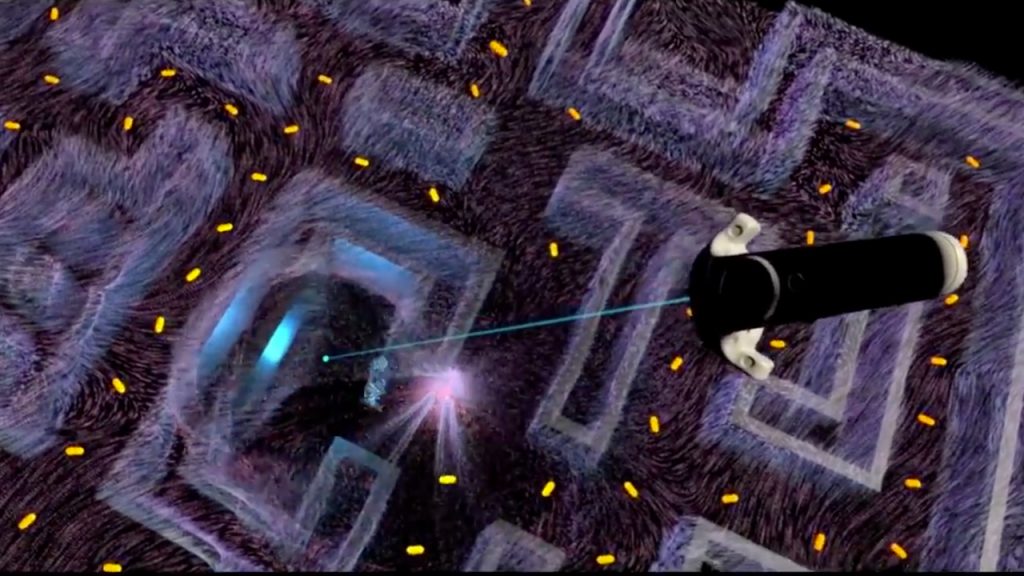

We created a scene reminiscent of Jon’s hospital life ethereal photographic point clouds: it started in a mind and morphed into various window tableau’s and corridors. With marching pills and ending Pacman style game interaction. It was to be a theatrical, tethered volumetric project, heavy on graphic cards and processing power, which was going to play around with your fragile notion of reality using actors and sleight of hand in the physical set. It was very ambitious.

The Vertical Slice

B. G. M. – When Oculus came on board it was conditional to us creating a “Vertical Slice” which makes sense in games but from a film perspective it was a real curveball. It essentially meant full commitment on style and interaction as well as the underlying code structure and overall form, like creating a mini film inside another film’s production schedule. This was a huge challenge to pin down considering we were still evolving as we went and discovering things along the way.

The Vertical did force us to make some hard choices and created the bedrock for the experience located around the hospital sequence. I do think it’s a more appropriate approach if the script is locked, but our conversations with Jon had only just started and in order to be true to his experience it meant we had to scratch a lot of the earlier ideas developed here as it wasn’t in line with Jon’s actual experience.

The Alpha version

B. G. M. – After the Vertical Slice we started to focus on the other scenes we had neglected and assembled a very rough interactive and uninspiring timeline of the various scenes we imagined. It was extremely ‘grey box’, with no pacing, and took a lot of imagination to believe in it.

This crunch crucially allowed us to see that we had far too many ideas, and it was a valuable exercise in descoping. We threw out about 50% of the aspirational content and interactions at this point. Pacing in VR is extremely difficult to feel. You can’t really get a sense of over/under stimulus unless you are in the experience. It’s a catch 22 for the development team who require specific instructions to create this vague sketch of a build. The lack of clarity was frustrating for them.

The Beta version

B. G. M. – After locking the form from Alpha, we committed to the various scenes in a sort of agile process. Reviewing builds and replacing artwork as it came in.

This was an intensively productive time, with the art team running many cg artists in parallel to land the finished content. We could start to see the scenes taking shape. There were maybe 189 iterations/builds pushed for the whole process and it wasn’t until the very last couple of months that everything really started to come together, with the pacing making everything click together and feel about right. But even when it was finished we couldn’t really see what it was until the feedback from the non experts and general public came in, and then the award.

At the core of GOLIATH: PLAYING WITH REALITY

A. – Much changed, then, in these years, and I wonder: what do you consider the core of this experience, the thing you wanted to keep from the very first moment?

B. G. M. – Perhaps the one thing that never changed from the very beginning was the ending. I knew that the first time I wanted people to feel they had a roof over their head was going to be at the end. I wanted to leave the story on a social realist note, being in the room of the protagonist and it being just an everyday moment. Not putting anyone on a pedestal and ending on a slightly positive note.

That was the focus throughout the experience: that no matter how crazy or bizarre it got on the journey, we were always going to land in Jon’s small flat and hear him hanging out with his friends. This was the core pillar for me in the experience: that we told an everyday story of someone who games but also incidentally had been diagnosed with a serious life affecting mental health condition, focusing on the everyday victories and not the prognosis.

On the design and the different scenes of GOLIATH

A. – I loved the 90s vibes of GOLIATH and the atmosphere in general. How did you and your team go about creating the different moments? Is there a scene that was particularly hard for you?

B. G. M. – The scenes and elements came out of various writing sessions and workshops, where we tried to find the meaning for the interaction.

I had loose ideas for the object of focus that were analogous to Jon’s story. I also had loose visions/dreams of elements and moments but they were extremely far away and vague and took a lot to tease them out.

We drew on the interview as much as we could, also. Jon went to a lot of arcades and excelled at gaming as a kid; so we worked with Antonis Papamichel (illustrator and storyboard artist) to reference games we would have remembered around that time. For the atmosphere I asked Aaron Cupples to start writing a chiptune score that would put us right back there.

I knew I wanted to be on a record player when Jon was talking about entering his psychosis. I wanted the viewer to be focusing on detail and the best way was to make everything enormous. The graphics evolve and improve as we go through the timeline of Jon’s story and loosely tried to reference graphic capabilities and style of the era that Jon was describing.

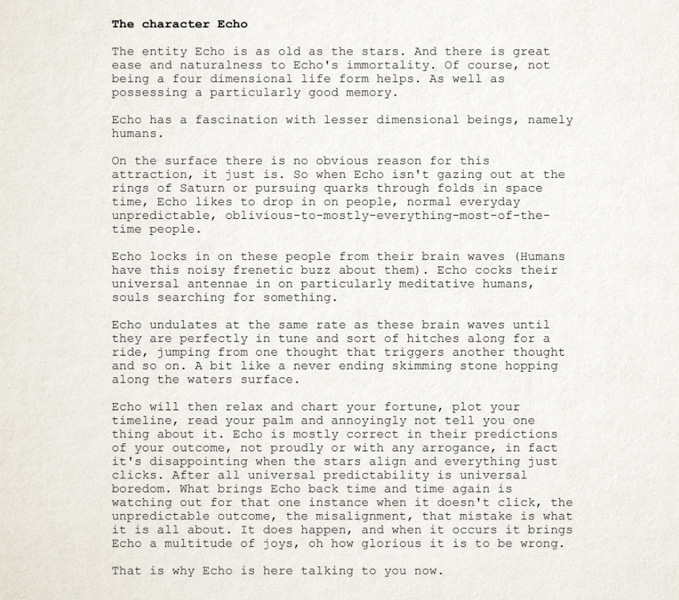

The most difficult scene was the one after the hospital, with the pills and the interaction. I still think that scene needed more time and effort to get right, it still bugs me. It went through about 6 or 7 different versions. The opening scene with Tilda was also very difficult, but once Tilda was cast as Echo, the tone and writing became a lot easier. That scene went through many personality changes and artwork updates before Tilda locked it in place.

A. – Tilda Swinton has indeed been a fantastic addition to this work! Can you give us some “behind the scenes” insights on working with her?

B. G. M. – Tilda walked up and we were in awe of her excitement and energy to play this role. We had written it with her in mind and surprisingly we found she had a passion for VR from previous experiences. Tilda understood the character of Echo and the reason for having a role like this in VR, one that speaks to the individual.

Working with her was an absolute joy. Often, when working with others, the collaboration can be difficult as you can spend a lot of energy whittling down the meaning. Tilda just reached out with her cosmic tentacles and really gave everything to find what we really wanted her to say. It wasn’t work… it was a pleasure. I can completely understand why directors scramble to have her involved.

A. – Speaking of voices: what can you tell us about the voiceover of Goliath himself? Are they actual recordings?

B. G. M. – Jon is Goliath. All the audio comes from actual interviews we captured either in person before lockdown and afterwards remotely on Discord.

I had met Jon a couple of times previously and chatted on the phone, but we hadn’t talked much about his experiences. He slowly opened up more through the course of the interviews. Jon has a powerful voice, a good timbre that resonates beautifully in the interior space we created. He is a natural performer when chatting to his friends but was quite nervous in these interviews, as were we. So the moments and memories we captured were raw and full of underlying emotion. Jon really hadn’t talked about it to anyone much and it was like trapped gases forming under molten lava. Jon would blurt out something quite profound at times. We just had to pace ourselves and slowly tease it out over the conversations which took place over the entire two year period.

Our last conversations to be included were very close to the end of Beta production so it was constantly evolving sound wise. May was in charge of the overall soundbed and framed Jon in the way which was most representative of his life but in a very condensed manner. Every word was weighed and has relevance. There is no fluff in Jon’s testimony.

A. – GOLIATH is currently available on the Oculus Store for free. It has fantastic reviews and many downloads… yet it is difficult to define: it’s not a game, but it’s not a documentary either; it’s a story, but at the same time it doesn’t follow the canons of normal storytelling. How do you see the future of distribution of works like yours?

B. G. M. – GOLIATH had a digestible core idea. Everyone we talked to got it straight away and it ignited their minds, they started to have ideas about it too. So this holds for all good ideas: for them to have an easily understood core premise.

As for mainstream audiences, I think it’s important that experiences like this talk to the medium as much as the message; the placing of the self inside these stories is the unique property that can add that other dimension to the story. So resolving who that is for your piece is very important. We wrote to an imaginary person that had never experienced VR or ever even played a computer game. I think that simplicity of approach helped us get a good reception from a broad range of viewers.

This was always May’s approach for Anagram from the beginning: to make everything extremely accessible. It took me a while to come round to this notion as I was very much interested in people discovering rather than being led. So I suppose the piece has that tension and therefore something for everyone. It comes from a place of respect rather than being patronising to people’s curiosity.

KATAYOUN DIBAMEHR (co-producer, Floréal Films) – We will do a year-long festival circuit with the film, which is important for the life of the project. Then we have an installation version of the experience that allows us to accommodate more than one person in the project with a performance.

This format was very important for us to keep because this is the DNA of Anagram and what Anagram does best: to use technology to reflect on the nature of our sense reality. For us this version will truly help with a LBE distribution, for example in museums, galleries etc.

We have two themes that are very important for us as subject matter to work on: mental health and gaming. For these two themes we want to enlarge our outreach and work with universities or any mental health center that is interested around this subject matter. Then there is the gaming aspect, so we want to bring GOLIATH to the gaming communities as well and talk openly about the issues in this community and break the taboos.

MAY ABDALLA – Also we are interested in what the piece might do in an educational context. Prior to production we had exploratory conversations with teaching institutions where medical students get their first introduction to the condition. We had run some workshops with people with lived experience and it was in that context that they had unanimously emphasised the importance that the nuance of the experience get shared with the medical profession as many had criticisms of their treatment.

Dr. Hugh Grant Peterkin, a practicing consultant psychiatrist in London, was on our editorial board and we are now working towards a research paper into a use case of the experience in the education context. A number of other university courses have reached out independently to discuss licensing in the teaching context. We feel there is valuable potential in this area.

To make new meanings and push the boundaries: the future of non linear storytelling

A. – The character of Goliath finds some sort of peace in online gaming communities. What can we find in VR today and what do you expect from the future of this medium?

M. A. – I’m excited about the power of non linear exploratory narratives. I feel we are working out the tools and the processes for a new generation that will use them to tell the next generation of stories. The language is very new and is being developed in collaboration with an audience who also move it forwards each time they respond to it.

When you take a risk and people get it, there is a leap forwards. And that’s extremely exciting! Storytelling at this time beyond VR is really changing. I am a child of Disney… the linear story of the hero with the redemptive ending. But you see a new generation operate differently. People talk about Tiktok as if it’s a short form medium, but really in its power is in a truly global fast responding community using a deep memory of memes and cross pollinating together in leaps. Its not necessary about status or IP, but quick responses and sharp ideas. It seems to be diverging rapidly, too. Young people are going to use story in a much more nuanced and personalised way. That is refreshing. Storytelling is going non linear and evolving at a massive pace! The tools make it this way, the tools of the future will enable much more deft expressions of experience. It’s moving away from that centred singular voice and to a much more personalised complex expression of a multitude of perspectives. There is a lot to unpack and learn from these innovative approaches to story. And there’s potential in VR- which begins in a place and therefore can be designed for exploration – to be a home for that, once tools and access and all that move on sufficiently.

B. G. M. – I personally became a gamer over the course of lockdown through researching this experience and also fleeing it at times. I believe it could be very exciting times ahead for the intersection of story/game and connection. How that will happen is really down to the industry and if it can recognise and incubate this potential.

Making VR experiences that land is extremely inefficient and risky as the language, toolkit and intuition isn’t fully formed. All of the elements are there already for those who can see the imaginative possibilities. The technology is just at that tipping point and there is a wealth of creativity to draw on. It really is the pinnacle of human endeavour in both technology and creative aspirations. It’s important that attempts and experimentation are isolated from the market’s viciousness. We need risk takers and visionaries to layout the ground work for future others to excel in this medium. We should not be too critical of anyone’s attempts to make something in VR. It’s all precious R&D for a future language. We need the Medici’s of our time to recognise that potential and commit to support. If that happens we can make new meanings and push the boundaries. If not this form will get kicked down the road for another generation to rediscover and reignite when perhaps the talent, technology and culture is in a more supportive place.

It is the medium where the collective dream space can mingle with our conscious selves and forge incredible moments that we can all share and in doing so understand ourselves better. I’m excited about it but also scared for it in the current creative climate where the arts are held to the same standards and justifications as the sciences.

GOLIATH: PLAYING WITH REALITY is an “animated virtual reality experience about schizophrenia, gaming and connection” directed by Barry Gene Murphy and May Abdalla, and produced by Anagram and Floreal Films. It is available on Oculus for all those who want to try it, who can also join the Discord community dedicated to it.

To know more about this piece visit the official website and Goliath’s page on XRMust Database.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.