When history reveals its human soul: a closer look at the content and meaning of END OF NIGHT and SHADOW, recently presented at CPH:DOX Inter:Active

Did you study history when you were in high school? I remember it was one of my favorite subjects, but always, when we read about it in our textbooks or discussed it in oral exams – so many dates and places! – I felt something was missing, an intrinsic part of what makes history relevant to us: the human component.

I remember that I used to imagine those events not just as a linear set of battles and facts, but as moments that someone had lived through. I tried for years to picture in my mind the faces of the people who were there and what it may have meant to them to experience those days. It allows you to create a personal connection with the past, somehow – with those who lived it, with their memories.

It also makes you realize that “learning from history” is not just about not repeating the same mistakes. It also involves recognizing that history is more than a metaphysical concept made up of faceless nations: rather, it is happening today, every day, to all of us… and we, like them, will be forgotten as individuals and become those faceless nations in our grandchildren’s textbooks one day.

I don’t know if it’s sad or not, all this, but I do know that this is why I love narrative works that bring history to life through the eyes of someone who was there and transform history itself from a great but distant event to the memory that this someone has of it. To me, that’s one of the most precious things a story can do: symbolically keep alive all those forgotten people that history is made of.

I’ve been lucky enough to come across several VR experiences that have done this – Angels of Amsterdam, Vajont, or the recent On the morning you wake, just to mention some.

END OF NIGHT and SHADOW, both directed by David Adler and produced by MAKROPOL, are two other examples of productions working in this direction.

Recently presented at CPH:DOX Inter:Active, both extrapolate from major historical events their most human dynamics but do so in very different ways – and not just stylistically-speaking.

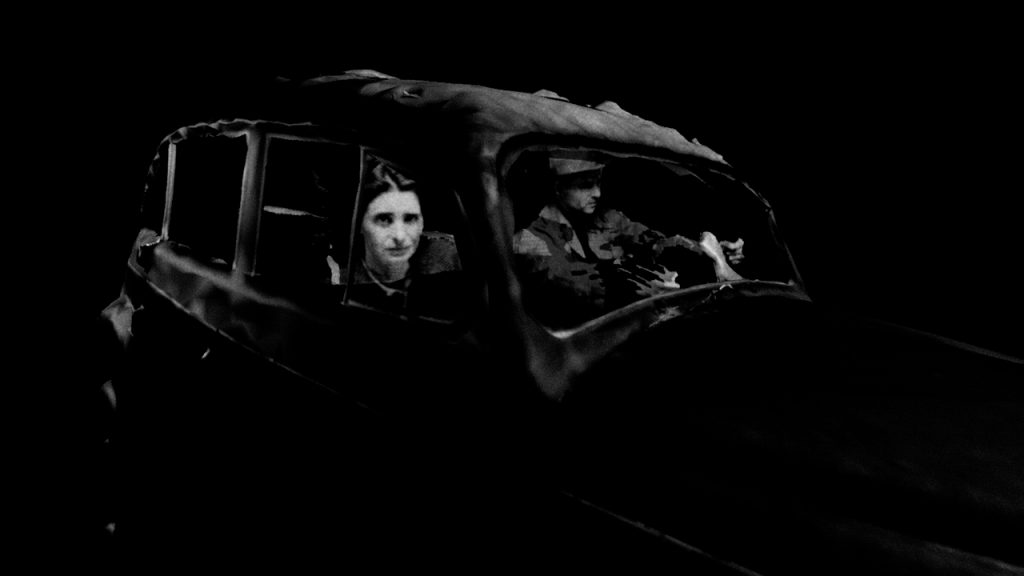

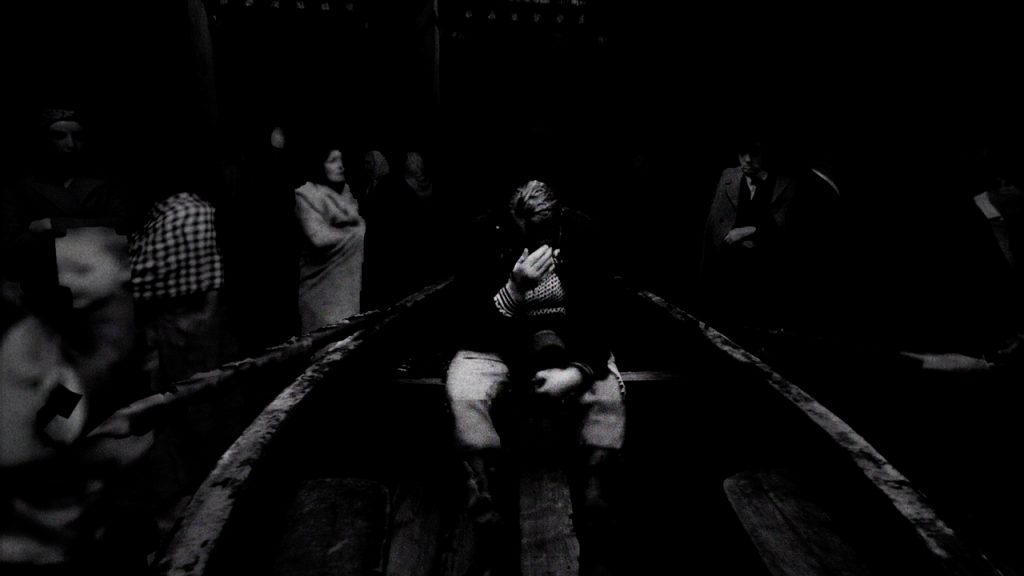

On one hand we have END OF NIGHT, a 50′ experience (which won the Best VR Story award at the 78. Venice Film Festival) that tells the story of Josef, a Danish refugee who escaped from Nazi-occupied Copenhagen in 1943 using a rowboat. You sit with him in his boat as he shares with you his memories of those days. You hear them but you also see them take shape around you and it is almost touching, for me, to see how David Adler was able to capture the essence of memories – a collection of small insignificant details with undefined contours and no impact on the “big” event itself, but which give the whole experience that someone went through that emotional quality that makes it last.

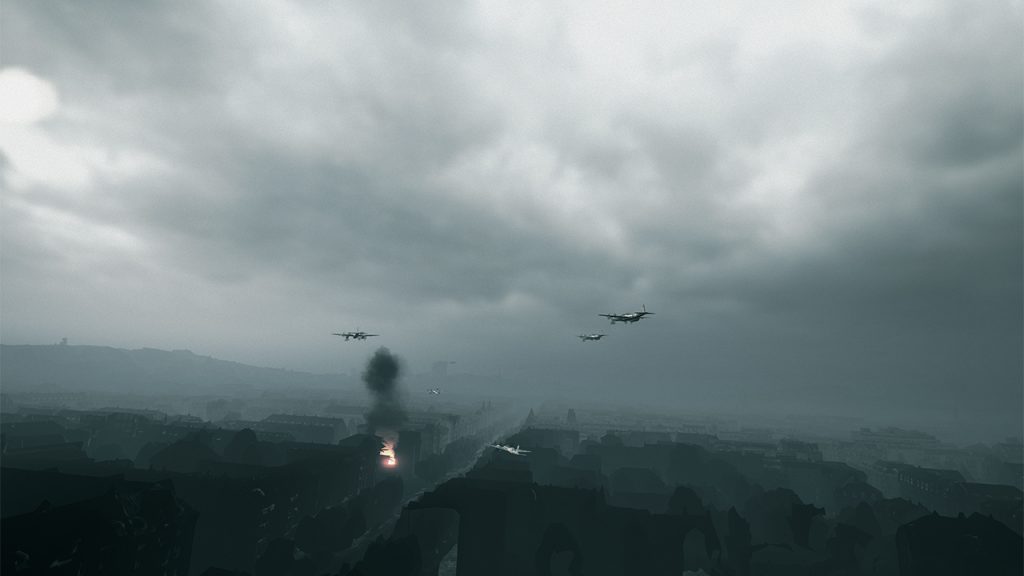

On the other hand, we have SHADOW, a realistic virtual reality experience that puts you in the shoes of a Royal Air Force navigator during a British air raid against Gestapo headquarters in Copenhagen in 1945. More than reflecting on memories, SHADOW helps you understand the emotional component of that specific event. What you’re being asked to do is to decide in five seconds whether the building you’re going to bomb is the right one or not. It doesn’t matter how prepared you think you are, how often you keep glancing at the picture of the building in front of you so you can learn it by heart. When you’re there, after minutes of nothing else happening, and you have to press the yes/no button but you can see very little outside and everyone is rushing you…. To say it’s not easy is an understatement. And to imagine what it was like in “real life”…. well, it is a whole other story.

We had the chance to discuss both of these works with director David Adler and find out more about their significance and what they represent to him. Here’s what he told us.

An interview realized in partnership with XR4Europe

On creating a physical installation around a VR experience

AGNESE – David, thanks for meeting us! How did CPH:DOX go?

DAVID ADLER – It went well! We got great feedback and a lot of attention especially on END OF NIGHT. It could be seen in a separate exhibition at the Jewish Museum in Copenhagen and it’s one of the first times we tried to create a physical installation around this piece. We are actually learning a lot just by having people come in and let them interact first with the physical environment and then with the virtual scene.

A. – I’m curious to know what you learned, but can you first tell us a little bit about how the physical part works?

D. A. – We set up a space with three rowboats that look a bit broken down and that’s where the three viewers sit to try the virtual experience. The boats look like the ones you sit in during the VR experience enough to allow the user to connect the two worlds. The smell of the material we used for them really gives you the feeling of sitting in a real boat, and as you virtually sail you can physically touch it and that makes the connection even stronger.

A. – What did you learn from all of this?

D. A – With any VR project, a lot can happen before the audience puts the headset on; that’s why for me the onboarding and offboarding moments are so important and you have to get them right. How do we welcome the audience? How can we make them more comfortable when they’re wearing the headset? After all, the more intrigued, curious but also relaxed we can make you before starting the piece, the better experience you will get from VR.

There’s also a very relevant emotional component to pieces like this – especially considering that END OF NIGHT was shown at the Jewish Museum: these are sensitive topics for some people, so being there and helping them get back into the real world is important. You’re not left to your own devices, but you’re helped out of VR both physically and emotionally. In our installation at CPH:DOX we also do a change of lights during the experience itself, so when you start there’s a certain light and when you take your headset off, there’s another one and it’s our way of saying to the audience: take a moment, you don’t have to rush out. You can take the time to bring your senses back to your body.

A. – As a user, onboarding and offboarding are often my favorite parts. You need to connect with someone before and after experiencing certain pieces, particularly when they are very emotional…

D. A. – An interesting thing also happens with VR and especially with this project: sometimes you feel very alone, sitting there on your own in the company of a fictional character. But then you take off the headset and you realize that there are actually other people there with you in the room who have just gone through the same experience. So what we’re hoping is to give these people the opportunity to start a dialogue about what they’ve just seen and experienced, if they want to… but certainly we don’t want them to feel pressured to do that either. I think it’s kind of like a social experiment.

A. – You are therefore not only learning things about VR. You’re also learning things about your audience. Did you create something similar for SHADOW?

D. A. – There is an onboard and offboard moment with SHADOW as well, but they are not as elaborate. We have seats that look a little bit like the seat you’ll be sitting in within the experience and they shake, like you’re actually on a moving plane. But we’ve also designed a larger version of the piece that we hope to build at some point.

There’s something about SHADOW – maybe the decision that you have to make so quickly – that would make for a very interesting multi-user experience. Having multiple people there, maybe making different choices, and then letting them discuss why they did what they did? I think one of the most important things that VR can give people is different perspectives and the ability to discuss them afterwards. So yeah, I really hope we get the opportunity to make that happen.

The importance of emotional resistance in telling a story the right way

A. – When you first presented END OF NIGHT at the Venice Film Festival, one thing you said really resonated with me: “In Josef, the character of the refugee, I kept encountering the conflict between wanting to tell my story and share my pain, with the fear of exposing my weaknesses and shame”. Is it something that it still stands true? What does END OF NIGHT mean to you today?

D. A. – I still feel that the stories I feel compelled to tell and the stories that are important for me are often stories that take me out of my comfort zone. I actually use myself as a test subject in that sense. I wonder why that story makes me feel that way, if I’m being overly sensitive or if I’m trying to protect myself or hide myself in some way, perhaps. And really, a lot of the power and emotion of the story I create comes out of those questions. If something is too easy to tell, it’s not working for me. It means I’ve lost that resistance to the story that is necessary to tell it well.

A. – It’s an interesting concept, the idea that struggling to get a story out there somehow makes it more meaningful. Is that something that happened with SHADOW as well?

D. A. – I was trying to get into that truth again with SHADOW. SHADOW is very different, but it confronted me with the question of how to represent war. Often the risk is to glorify it or make light of historical events. Instead, I wanted to convey a story that gave a sense of adrenaline but also respected the subject matter. Two things that are constantly fighting each other because we are so used to movies about war, and even more so to video games about war, so the idea of war as excitement. This was something I had to fight against because even though it is an exciting story, it touched many many people. There’s also the issue of national pride and other related social issues that you have to deal with when dealing with historical events, so I had to work with it as respectfully as possible. I feel like we came pretty close to what we wanted to achieve.

A. – Absolutely. And one thing the piece makes very clear is how hectic and dramatic those few seconds are when you have to make such an important decision. I also realized how many factors play a role… like the fact that you can’t really see well behind the dirty windows and everything looks similar from above…. It became very real very quickly.

D. A. – Those few seconds determine the whole outcome of the piece, and I felt like we needed to get those 12 minutes in before they came to justify them happening then so quickly, while dealing with movement, and motion sickness, and all those things that make the decision much more difficult and sudden.

At its core, though, SHADOW for me is basically a little play with two characters, the pilot and the navigator, and it was interesting for me to mix that play with that intense five-second decision.

On the importance of connecting with characters

A. – In END OF NIGHT in particular, there’s a strong sense of connection that you build with Josef, the main character. You look into his eyes and you feel like you’re there, sitting next to them.

D. A. – This is why, for me, it makes sense to work with VR rather than a film or a novel: you meet that person, you sit with them. No doubt it doesn’t work in every single narrative, though. You have to feel like it makes sense for your user to meet that character in the VR space. But when that happens, and they connect, projects get a lot easier creatively because you can always go back to that audience/character connection and that’s what’s important, that’s what we need to find.

A. – SHADOW is the virtual reality companion piece to Ole Bornedal’s film “The Shadow In My Eye”. How do the two media relate to each other?

D. A – SHADOW is a virtual reality piece that aims to expand The Shadow in My Eye but also reinterpret it. Ole and I have a good dialogue but we are very different. So for me, it was very interesting to see how he would portray something and then compare it to how I would discuss the same thing.

In the film, there are several pilots and you spend a lot of time with them, but not to create the same kind of intimate connection that you find in SHADOW. It’s a great film, with a lot of actors and characters, and it shows the same event from different angles.

In SHADOW, on the other hand, it’s just you and another pilot, and because VR itself requires faster narratives, you’re also faster at creating a connection with them. You also have one angle of the story and so you focus on that and you have to react to that.

A TASTE OF HUNGER, my previous work, was also my interpretation of a feature film, a piece where I could just focus on what my character was thinking and expand on her life. It’s interesting to see how VR works in that space: it allows you to just watch the narrative and the characters without worrying about a large-scale production. In some ways it allows for an easier way to look at the story.

An intimate and human look at a significant historical event

A. – Both END OF NIGHT and SHADOW are very intimate pieces but at the same time look at relevant historical events to bring out the human element. What kind of historical research did you do to develop such an intimate journey?

D. A. – We did extensive research on both pieces, but with END OF NIGHT we touched on the human side quite early on: reading people’s diaries and letters, interviews… it all became very personal quickly, because we had very intimate narratives that were not about the whole war but just the individual experience of it. Obviously the global conflict had a big impact on people’ lives, but I didn’t need to show the larger story: it already resonated with the characters living it.

With SHADOW, it was a little harder to come up with those kinds of personal stories, partly because the military often has to present things from a very specific point of view, the “we were brave and this is what happened.” So it was hard to get to the more human aspect behind the uniform. Still, there were human casualties and military stories behind this event connected to what we wanted to tell and we just needed to find them. It just took longer to get past the initial facade.

A. – Did the people you contacted about END OF NIGHT get a chance to watch this project once it was completed? Was there anything anyone said about it that stuck with you?

D. A. – Some friends, whose grandparents and parents had fled Denmark, actually watched it; and so did someone whose name was Josef, like the character of the same name in END OF NIGHT, and who himself had had to leave the country, which was very interesting.

I think it was tough for them to see this piece and get through the experience since they were so close to such a historical event… But it was also a somehow healing moment. One of the women who watched the piece said to me that the world could finally see what she had been carrying around inside herself for years and it was liberating.

Stories like this have a tendency to be passed down through families, and our approach focused not on the event itself but on how it was told by the people who experienced it. Having grown up with grandparents who fled Europe and family members who have been through a concentration camp, for me it’s all about how they tell their story, how they remember it: details like standing on a train platform and being given a loaf of bread and that loaf of bread is actually what helped you get through the whole war….

From that perspective, telling this story in the right way was the first ambition behind END OF NIGHT. From there we started working on our research and tried to capture Copenhagen’s angle and the consequences of what happened, sure. But the longer I stayed on those interviews and letters, the more I realized that they resonated exactly like the narrative tradition expressed by people like my grandfather.

A. – What elements of this type of storytelling did you really want your piece to convey?

D. A – First of all, that ambivalence between feeling that this was an important story to tell but also the pain of having to tell it. That’s often an element that these stories share and it was a key aspect of getting me into the project.

I also wanted to portray those little details that make up the narrative of memories. For example, at one point you see a man to your right who is a cop and he’s looking at his book and wiping his glasses. I don’t even know why it was important to me to include something like that, but I read it in one of the journals and I knew it had to be there. Details like that reflect the larger story and make a connection between the large-scale event and those little personal things that make it so emotionally dense.

On the fragmented quality of memories

A. – It makes a lot of sense, though. Memories often aren’t about the big thing, but are more like a collection of details that wouldn’t make sense to others but to you are what gives them their unique flavor. I really liked how you worked on this concept visually as well. The way you convey how memories are somewhat fragmented through some very interesting technical choices is amazing.

D. A. – We’re working with memory but also with the idea that it’s being told and now it’s deteriorating. Every time we tell something, as human beings, we emphasize one detail and omit another, some aspects are enhanced, others begin to fade.

In END OF NIGHT we delve into this a bit: it’s not an easy story to tell and you’re no longer sure what Josef remembers correctly, but that’s the nature of memories themselves…. they’re changeable and they deteriorate and they have their own quality. I wanted the physicality of memory to be represented in the piece somehow. To give it texture and density.

A. – The choice to make these memories physical conveys the idea that they are something that doesn’t belong in the past but is also happening now, today. What would you like the audience to take home from their END OF NIGHT experience?

D. A. – The one thing I hoped for from the beginning of this project was that people would feel that they had really met Josef. They know enough about him and they’ve spent enough time with him and they’ve seen some painful things, but maybe they’ve also laughed with him, that they feel they’ve actually met him. You can agree with his choices or think he should have done things differently, it doesn’t matter. But at least you acknowledge the fact that he’s there and this is his story. That, I think, is what this project should really be about.

Finding an identity for VR and connecting it to its audience

A. – Do you have any plans now for END OF NIGHT or SHADOW? Are you going to continue the festival run or maybe present them elsewhere?

D. A – Where to show these pieces and how is an interesting question. VR hasn’t found its place with audiences yet, and I think the next big piece I’d like to work on will have to discuss how to find that audience, and figure out how to connect with them. VR works are still being compared to both movies – which have cinemas and streaming services and a lot of other tools to connect with audiences – and the gaming world, which is even more directly connected with its audience. VR has yet to figure out what it is. Is it a game? Is it narrative? Is it art? Should we be watching a VR production at home or in a gallery? Should we even be at film festivals?

I’m very much of the idea that the reason I do VR pieces is to connect with people. I do it for the audience. I think it’s really important to meet them and be involved and listen to them. And I think our next big piece needs to evolve along those lines.

A. – After this long period of isolation, the word “connection” sounds even more relevant. Have you learned anything about it over the last two years?

D. A. – Yes, I’ve learned a lot. I was very lucky – being a technology-heavy production, everyone was pretty used to video calls and working online, so it didn’t seem like a big challenge. Nothing stopped us in that sense. But definitely working with art direction and actors was pretty hard to do remotely. A lot of it is in the pauses between what you’re saying, the body language, all reactions that get kind of lost in online communication.

I actually learned more when I got to see my audience live. We did a couple of satellite screenings, and for me being in the same room with the users, seeing how they react when they come in and then when they leave, maybe being there for a follow over…. that’s what’s really important and where I’ve learned the most.

And it’s definitely not just one thing I’ve learned, but a sum of things: what I see from their reactions, what I see them take home after the screening is what gives me the energy to move on to the next production, hopefully stronger and a little wiser. Never underestimate your audience, they are always very willing to be involved in the story and the world, so you have to respect them.

A. – The audience can absolutely read behind the lines and know if you’re trying to trick them, even when you don’t think they will. But if you give them something of yourself, they’ll give you back an even bigger part of themselves.

D. A. – Sometimes you find yourself in productions that are looking for easier solutions or wondering if the audience will really understand what they’re doing. But the point is, you have to trust your audience, trust that they’re investing in your experience. After all, you’re the one who shapes the stories and shapes the worlds as a storyteller and artist, but experiencing them is your audience’s job. And that’s where you really connect with them.

END OF NIGHT and SHADOW are VR experiences directed by David Adler. Visit Shadow’s official website and MAKROPOL’s projects page to find out more about them.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.