Part of the Sundance New Frontier 2022 lineup, Child of Empire is a VR experience in which the discourse on the political situation gives way to a broader reflection on the effects of conflict through a meaningful and human conversation between two people who are different but share the same pain.

One of my favorite works at Sundance New Frontier 2022 was Child of Empire. Created by artist Sparsh Ahuja and VR producer and director Erfan Saadati, written by Omi Zola Gupta and animated by Stephen Stephenson, art director for the piece, Child of Empire tells the story of the 1947 partition of India and Pakistan as seen through the eyes of two survivors of the two different sides, Ishar Das Arora and Iqbal-ud-din Ahmed.

I didn’t know much about this historical event, so I came to this piece with very few preconceptions, and a near blank slate that I hoped the experience itself would fill in.

And filled it, it did, right from the first two minutes, where 200 years of South Asian history are presented in one of the most effective premises I’ve ever seen in VR – a narrative choice I won’t spoil for you, but one that felt both familiar in the way it recalls other cinematic narratives, and yet completely new in relation to this specific medium.

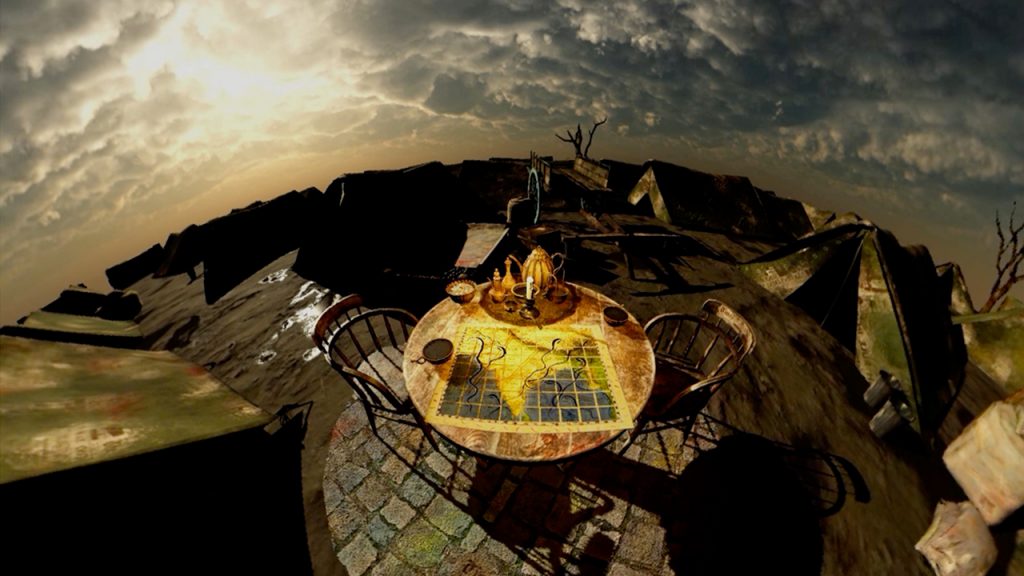

The initial scenes are frighteningly powerful and immediately grab your attention. A red river opening up beneath your feet to symbolise partition, the camera slowly moving away, rising to frame everything from above – a city that is now also a map of the country – and the title of the work, Child of Empire, looming on the horizon: a scene that vibrates with the power of cinema and an immersivity that only VR can offer.

Yet, after this majestic and intense opening, Child of Empire leaves history almost on the sidelines and brings you back to the personal stories that history itself often forgets – but which are even more impactful on our awareness – with a rarely seen delicacy that permeates the entire work from there on.

And not only is delicacy reflected in the narrative content (in this regard it is worth mentioning the scene of the walk in the desert, in which everything – from the light, to the conversation, to how death is conveyed – is poetry). It can also be seen in the artistic choices that, on the one hand, elegantly underline the cultural identity of the two populations and, on the other, highlight the commonality of their experiences.

We talked about all this, and the meanings of Child of Empire, with co-creators Erfan Saadati and Sparsh Ahuja.

A human conversation on the effects of war and conflict

AGNESE – Child of Empire is a beautiful and meaningful piece. I loved the art design, how you worked with the different timelines, the memories. And, of course, its meaning was an important one. What is the story behind this work?

ERFAN SAADATI – I met Sparsh Ahuja (a/n co-creator of Child of Empire) three years ago. At the time he was working on a VR project, a 360 video to virtually take his grandfather back to the places he came from. Being a VR producer myself, when I read about this project in a VR group on Facebook, I immediately liked it, and I liked Sparsh’s ambition. We met and started working together to create something that could speak to a wider audience.

Originally, we were going to make a more traditional documentary using 360. But just as we were starting production, Covid19 came along and we had to rethink the whole process. It was actually for the best: taking the animation route allowed us to be more artistic, more poetic, and shifted our original concept from the story of a single child (Child of Empire) to a conversation between two different people. We started to look more closely at the technology available and decided to make the piece a little more interactive so as to ground the viewers in the experience, make them feel part of the story.

The choice to create something a bit more interactive allowed us to work on the flashbacks in a very smooth way and helped us to connect the different parts of the story. If we had just filmed those scenes, it would still have been a good experience, but more disjointed and, of course, a completely different work.

A. – There are some very innovative elements in this work.

E. S. – In most of the works I’ve done in the past, there was usually a voiceover accompanying the various scenes. But in this way you sometimes end up missing what they are saying, or missing part of the visuals. In Child of Empire the voiceover is a conversation between two people that you join at the beginning of the work. You’re curious to see for yourself what they’re talking about.

It’s a decision I’m quite proud of: having a conversation rather than just a voiceover? It felt more natural somehow.

A. – It certainly does! Another thing I really liked was the premise: the initial theatre to present the history of India and Pakistan and then the next scene, where you see the city and the camera pans up and the title appears. It was at the same time very cinematic and very immersive.

E. S. – We debated a lot about how to work on that opening scene. We had to make sure that people understood the context of the story. It was very difficult to compress 200 years of history into about two minutes, but I think we managed to give the audience a good overview without blaming any particular party. And that was another very important thing for us: that Child of Empire grounded us in the human stories of real individuals rather than just in a political event from textbooks with statistics.

It’s not a definitive account of the whole history but we wanted it to reflect on the effects of war and conflict on survivors.

We had a large board of advisors and one of our producers is also quite knowledgeable about South Asian history. So everything was fact-checked to make sure it was accurate. And of course, the personal stories came from the interviews we conducted. We took some artistic liberties in the conversation, but the flashbacks are 100% accurate and the story is also obviously accurate.

Symbolism and imagery from both sides of the border

A. – Some of those flashbacks were really beautiful and touching. The scene with the caravans was incredibly powerful, both in its meaning and its visuals.

E. S. – We have to give credit to Stephen Stephenson, our art director, for that. He created all these amazing environments and characters, doing an amazing job with very limited resources. Stephen saved the whole project, made it really beautiful. And we’re just taking credit for it (laughs)

A. – Two concepts your team mentioned during the artist spotlight at the Sundance Film Festival were symbolism and imagery, which for this piece reflect both sides of the borders. It’s something I’d love to discuss!

E. S. – From the very beginning we wanted the retelling of history to spotlight a South Asian perspective. We’re in a Indo-Islamic monument that stages a string puppet sort of style, native to Rajasthan, India. A majority of the cut outs you see are sourced from Indian miniature paintings from that period.

Then the most obvious moment is the scene in the train, where they talk about the deity who saves them and an image of Krishna appears: it is obviously a Hindu reference. In the caravan scene, however, when Iqbal recounts his story and people pass, we had their bodies transform into verses of the Quran. The imagery felt right.

It was also very important for us that elements such as the buildings and clothes also reflected that time and space. We took some creative freedom in one of the first scenes in the village: on one side you see a mosque, on the other a temple. It was our way of balancing these elements. We wanted to tell the story of these two survivors who are different in their origins, but have a single thread running through them; so we had to basically create an experience that felt like one journey but divide it into different sections and assign them to the different characters we had .

A. – I also noticed some nice details. Like when you’re in the dark house and the fire next to you turns into the burning village seen from above. Little details that made Child of Empire more effective, in my opinion, and somehow more alive. I really appreciated them.

E. S. – Stephen and his team worked tirelessly to make sure we had all these details. I’m very glad you noticed them!

A. – Talking about the team, it is very international. Was it difficult to manage the work in this way?

E. S. – Some of us operate in London, others in India and Pakistan. We also had a development team in Romania. It was challenging, of course, but at the same time it allowed us to create great things. In terms of the sound design, we were able to get authentically sourced sounds from India and Pakistan, and that made a difference. And I think having an international approach makes for a very good experience.

Also, our two actors worked from different studios, in Pakistan and India, and we joined them from London to direct them. Their conversation was recorded with Zoom. This is the first time I’ve done something like this and it was very interesting: they are fantastic professionals and they made everything very easy for us.

VR as a peacebuilding tool: on Project Dastaan

[Here co-creator Sparsh Ahuja joined us to discuss Project Dastaan (داستان/दास्तान: “Story”), described in its official website as “a peace-building initiative which examines the human impact of global migration through the lens of the largest forced migration in recorded history, the 1947 Partition of India and Pakistan”]

A. – Sparsh, you are the founder and CEO of Project Dastaan, with which you worked on Child of Empire. It’s great to see VR being used to bring about peace and for its educational applications. Can you tell me more about that?

SPARSH AHUJA – Project Dastaan is a peacebuilding initiative reconnecting individuals displaced during the 1947 Partition, on either sides of the border, with their ancestral villages through 360 Video/VR. The Project serves as a peace-building initiative in the subcontinent and as a commentary on the human impact of migration and colonialism.

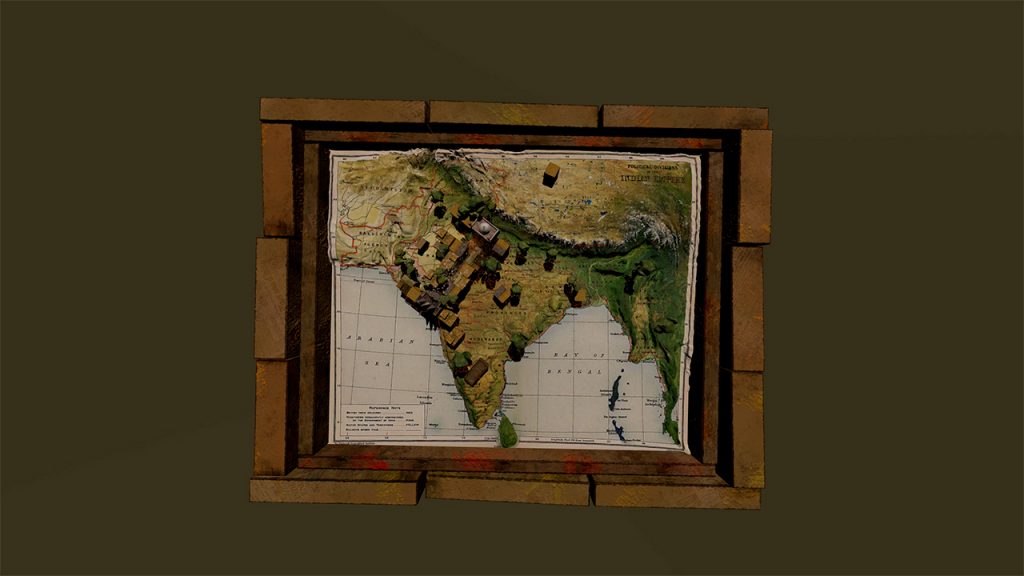

The 1947 Partition of India and Pakistan was the largest forced migration in recorded history. More than 14 million people were forced to move and over one million died in the process. Partition continues to be a lived experience for many people across the subcontinent, as most have not been able to return home.

By essentially redefining the terms on which the “homeland” was constructed, migration during Partition impacted witnesses’ own understanding of their native cultures – once shared across the subcontinent – into smaller ethno-nationalist blocks. Pakistan became the new homeland for Indian Muslims – it developed its own people, defined new geographical boundaries, and gave its citizens a tabula rasa on which a new cultural identity, shaped by sense and control of place, could be crafted. On one hand this was liberating for the Indian Muslims who had fought for their right to self-determination during the colonial struggle, but it also resulted in widespread social disorientation amongst the average citizen. Across Pakistan, both colonial and dharmic roots in culture were deliberately shed to achieve this end.

Across the border in India, a similar cultural transformation took place. The state, backed by the fervor of independence, successfully rallied ideas of a Hindu “homeland” to generate a shared Indian identity across a geographical area as diverse as Europe in its ethnicities and languages. Distinct political decisions towards this Hindu society, coupled with the void left by the Muslims who had migrated to Pakistan, meant that the Muslim contribution to Indian history slowly took a second-hand status.

In the aftermath of the four wars fought between the countries, the saddening reality is that the average Indian and Pakistani, despite their common history, language, culture and religious practices, have never actually met each-other. This lack of cultural exchange allows for misconceptions about the “other” to foster, and of course electoral politics furthermore encourages this “othering” process, as pitting communities against each-other is often an easy way to generate popular support at the voting booth.

Against this historical backdrop of mistrust and colonial violence, Project Dastaan seeks to transport survivors back to their long lost birthplaces, and in doing so, evoke memories of a shared history and culture, before these religious identities were hardened. Here’s a really interesting short video that explains our process and the emotional impact it can have on the participants – it’s far more powerful than anything I can share here!

On the people who inspired this work

A. – Did you have specific inspirations for Child of Empire?

E. S. – Abbas Kiarostami. He is a legendary Iranian director at the intersection of documentary and fiction. He was also one of my old teachers, and he passed away a few years ago. What we wanted to do with Child of Empire was to create a work that was something more than fiction and something different from a documentary, an engaging story where the lines between the two were blurred. In that he’s been a huge inspiration. He’s also the main reason why I am a filmmaker and a creative today. Everytime I can I mention him. I just want to keep his memory alive.

S. A – It is not a coincidence that “Dastaan” from Project “Dastaan” means “story” or “tale” in many Central Asian and Indian languages, notably Persian, Urdu and Hindi. Dastaangoi is (or was – as it is sadly dying out) a 13th century storytelling form from the subcontinent – it combined stories from as far as the Arabian Peninsula, to the Sufi masters of Central Asia, to the Vedic tales from the Ramayana and Mahabharata I was told as a child. For me, then, it represents a homage to the religious and cultural unity that makes us South Asian, and a challenge to the divisive communalism that unfortunately plagues the subcontinent today. By naming this Project as “Project Dastaan” I not only want to invite my viewers to look back at the beauty of a pluralist past, but also to emphasise that what I am trying to do is tell individual stories rather than the “big picture politics” of Partition. As a child of diaspora, I have come to understand that the important stories of migration are not those of the politics that dictate it, but the people it uproots.

In terms of specific pieces of work, one of the journalists I particularly admire in this field is Anna Funder, who wrote the critically acclaimed Stasiland. Stasiland describes the experiences and tribulations of East Germans, once behind the Berlin Wall, in a post-GDR world. She interviews both victims of the regime and ex-Stasi who feel trapped between nostalgia, and life in a new Germany, which is free, but has failed to deliver on its consumer-driven promise of happiness. Funder’s work was one of the biggest motivators for me to study oral history around the Partition of India and Pakistan. The stories of Stasiland taught me many valuable lessons, but one stood out. It doesn’t matter whether you are Indian, Pakistani, East German, West German, Israeli or Palestinian – memory is often less about the truth, than what about we want the truth to be.

On working with VR and choosing accessibility

A. – Tell me more about why you chose VR for this story.

E. S. – VR has often been used as an empathy machine. I’ve been working in VR and 360 for 11 years – many pieces I’ve seen are VR for the sake of VR. But working at Child of Empire with our production partner Happy Finish, the company I work for, we realized that this story needed VR. There are very specific projects that really lend themselves to it. Notes on Blindness, to name one. It puts you in other people’s shoes in a sensorial experience that you wouldn’t otherwise have access to. We hope to do the same with this work, to help the audience get an idea of what it’s like to make this kind of journey away from home.

We’re working on other projects that go in this direction. One of them is part of the National Autistic Society (a/n the video is available at this link) and allows the viewer to experience an idea of sensory overload, a disorder that people who have autism sometimes go through. So, I think it’s very important that when we use VR we don’t just do it for the technical possibilities it offers or because it’s cool, but rather we need to see it as a storytelling tool and ask ourselves if our story fits. It’s true that sometimes you don’t have as much artistic freedom as you do in film, but its ability to put you in someone else’s shoes is unparalleled.

A. – I loved that you made Child of Empire accessible for the Oculus Quest: I know it can be hard to work with, but this way you reach a wider audience, people who might gain some important insights from a work like this. This accessibility has the potential to make this piece more impactful.

E. S. – The original prototype we had was for the Oculus Rift; then we started playing with Quest because we wanted our actual distribution to go beyond festivals. We wanted to bring Child of Empire to museums, schools, etc. Quest isn’t necessarily the easiest device to create a work for, but it’s certainly the most influential and we want people to experience this work! We created it for a wider audience, for people who aren’t familiar with this part of our history, but especially for young adults with a South Asian heritage. There are many people in the UK, in Canada, in the US who have a general idea of what partition was – they got it from the stories they heard from their grandparents and parents. However, they have not engaged much with the subject and we want to offer them the chance to see with their own eyes and imagine what it was like.

A – It’s a way to preserve memory and share it. This reminds me of what Omi Zola Gupta, writer of Child of Empire, says in your Sundance Meet the Artists video: this film is “a space to bear witness and heal together”. What would you like your audience to take home after experiencing this work?

E. S. – This is an interesting question. I want them to have an understanding of the history, some of the historical circumstances that led to the founding of these countries. And then the main thing that I hope people grasp is that despite our differences, the victims always have a common experience.

When you start the experience, you have two characters who disagree with each other – we were right, you were wrong, etc. But in the end what remains is: “the human suffering of this event was entirely avoidable/not inevitable, and shared on both sides of the border” and that’s something that really reflects our journey as creators: we did more than 40 interviews with different survivors and almost all of them started from a political point of view – Indians are wrong, Pakistan is wrong, and so on. But those interviews, they all ended with a reflection on what those people went through, a sort of understanding of the other side, of the victims on the other side. I hope that people can draw from this experience similarities with the victims of all kinds of conflicts. It is a story that gets repeated over and over again, even today.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.