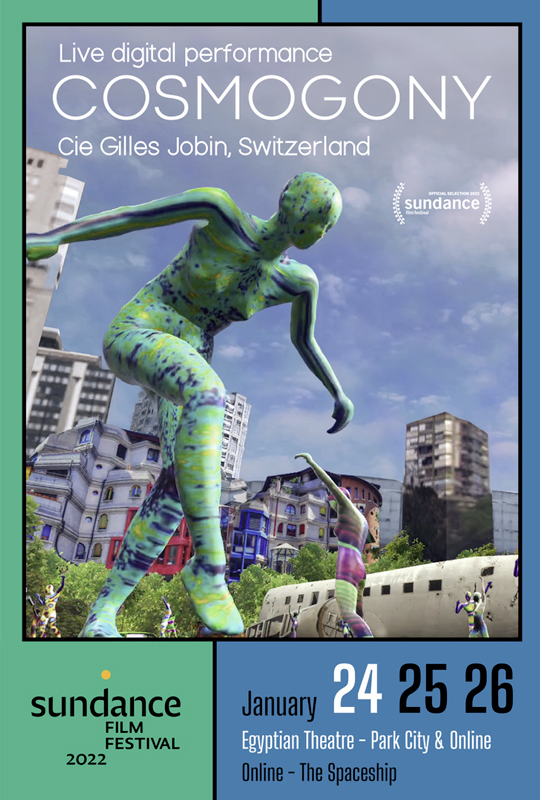

Presented at Sundance New Frontier 2022, COSMOGONY is a live contemporary dance piece that allows the audience to join in the moment when the dance comes to life. We discussed this work with lead artist and choreographer Gilles Jobin.

There is a digital place at the Sundance Film Festival called the Cinema House: one of my favourite locations, because it really looks like an old cinema, complete with carpet on the floor, brown chairs, and dark red curtains framing the stage.

It is the place where, as a tiny avatar wearing your face (and sometimes not actually your face, or so I hope – yes, I’m pointing at you, unknown person who looked like a chihuahua), you go to listen to artists’ spotlights, join Q&As, sometimes watch pre-recorded videos of the projects presented at the festival.

But the Cinema House is also a proper theatre and that’s where a very special experience of the immersive lineup was made available this year. This experience is Cosmogony, a live biodigital dance performance (and we will come back to the use of the term biodigital in this context later) where 3 dancers, dancing from a studio in Geneva, are motion captured so that their dance can be projected into a 3D environment and enjoyed by the audience exactly as it comes to life.

Choreographer Gilles Jobin has toured several festivals in recent years, increasingly intersecting the world of contemporary dance with the XR space. Together with his technical and dancing team he makes of Cosmogony a technologically impeccable work. Yet, it’s more than that, and it doesn’t matter if you don’t know much about contemporary dance: what you see on the screen, the rhythm of the music, the way the dancers move… all this slowly draws you in. You feel like you are enveloped by this piece, sucked into those eerie places, and there is something hypnotic about it all.

But Cosmogony also opens up interesting questions for those in the XR field. One of them – the one I heard discussed the most – was why create a live show when no audience interaction is required. This is what we all expect when a work is in real time, and I admit at first I wondered about that too.

Until I realized something. Looking back at a piece that had a similar approach and was very popular in 2021, DREAM by the Royal Shakespeare Company, I realized that what I liked most about that play was not the frankly limited interaction it offered – more of a distraction feature than an actual immersive tool. No, what I liked was the idea that I was sharing that performance with hundreds of other people from all over the world, each one of us from the comfort of our homes. I was there and they were there, and the artists were there and everything was being created at that very moment.

This is what happens in Cosmogony. The details they add to remind you that what you are watching is live (the overlay of the avatars with the real dancers) worked effectively in creating an experience and reminding you what is really happening in front of you at that very moment.

We discussed all this with Gilles Jobin and are publishing the interview almost in its entirety, particularly for those who, like me, are not very familiar with the world of performing arts.

Discovering VR and motion capture: from WOMB to VR_I

GILLES JOBIN – I still remember the first time I saw a 3D film with dance scenes: it was Pina 3D directed by Wim Wenders, and as soon as I watched it I realized that stereoscopy was the next level for us choreographers. Together with the dancers, choreographers are the real 3D experts: we work and move in 3D, we use our position in space but also the space between people to create tension. Choreography is a language that fits new technologies very well, because it is concrete and abstract, it is not narrative but it carries meaning.

So I decided to shoot my own 3D film, called WOMB, and it was while working on it, in 2016, that I discovered the possibilities offered by motion capture. It all came together in my next piece, VR_I, which opened at FNC in Montréal in 2017- the piece won the audience and innovation award – and it was selected for the Sundance Film Festival and the Venice Film Festival in 2018 (a/n read XRMust’s interview about VR_I)

Technology offers new possibilities but also has limits. But a theatre is a limited space in itself: the audience is frontal, and the space available for the performers, the stage, is contained. These limitations force us to be hyper-creative in order to create endless stories in a limited space.

What these technologies have brought us is a greater range of possibilities. You can play with space, size, scale and create incredible scenarios… Multiplications, giant dancers 35 metres tall… Digital technology allows us to imagine choreography without the limitations of the physical world.

Questions about immersive realities to ponder

G. J. – A very relevant aspect for me is that in a 3D environment – specifically in virtual reality – the experience is in real time. It is a very intense feeling because you are living in the moment: you are not in a cinema watching a film, you are inside a space, a situation you are really immersed in. Performing art is about being together – the artists, the audience, the technicians – and whatever your role, you are part of the performance. The dancers, the technicians, the audience, are synchronised in time, they all grow old together as they spend the time of the performance together. Their experience is lived in real time.

When we made VR_I, we had five users interacting with each other in the piece but moving within pre-recorded animations of the dancers. The work established a natural relationship between the audience – who were having a real-time experience – and the dancers, who appeared to be moving in real time but were actually recorded. The trick to establish the relation between the participants and the interpreters was that the giant dancers did not pay attention to the human participants. So there was no real interaction between the world of the dancers and the world of the spectators but the situation was clear: the spectators were the invisible tourists in a VR world. The real-time interaction was rather between the participants.

VR_I triggered my thought process about the meaning of real time. What is a real time experience? That question led me and my team to investigate technologies allowing the interpreters to perform in real time into a digital world. When Covid19 arrived, for us – remember, we are a stage contemporary dance company – the immediate solution to the crisis was to go digital. We acquired hardware equipment for motion capture and our fantastic team of artists and technicians investigated the feasibility of remote digital performances in real time. It allowed us to work with total liberty without the constrain of a commercial motion capture studio.

When lockdown arrived in Switzerland in March 2020 we were working on a duo on stage using real-time motion capture. We decided to pause that creation and recycle the real-time technology we developed for the onstage piece to digital. In June we presented a prototype for a live show in VR, La Comédie Virtuelle-live show, to the curatorial team of the Venice La Biennale and it was selected for the competition.

In retrospect, it was a risky plunge into the unknown for curators Liz Rosenthal and Michel Reilhac. They took the risk with us while our incredible team studied the technical solutions. We performed the piece every day during the festival in front of a connected audience, some days we had connections from 14 different countries, watching a dance piece together in real time. That was mind blowing.

COSMOGONY at the intersections of two worlds

G. J. – Cosmogony is an attempt at live cinema, or call it live animation. It can be a 2D projection on a screen or a video mapping on a building. The dancers perform live and the spectators are present, in real time. The 2D projection works within a frame and with camera movements. As a director I control both so, unlike in VR_I or a stage piece, I decide what the audience gets to see. In this sense Cosmogony is a bit different from my previous works where the spectator/participants could choose their own point of view.

In VR_I the spectators are immersed in real time in a digital world, in Magic Window (2019 augmented reality permanent installation) and Dance Trail (2020 augmented reality dance piece) we invite virtual dancers into our real world. My interest in the 3D world is precisely that: the multiplicity of accesses to digital space. We use hardware like tablets and phones and VR headsets to open portals between the virtual and the real worlds. I am in line with Shari Frilot (a/n programmer at the Sundance Film Festival, read our interview on New Frontier 2022) when she talks about the biodigital continuum: we are already connected on a daily bases in and out of the virtual world through many doors.

Cosmogony is both a synthesis of our four years of digital investigations and a crowning achievement of what we have developed during the last 2 years of COVID. We feel the piece is complete, it is a joy to dance to, trippy and joyful, we are very proud of it!

On why to make Cosmology a live experience

G. J. – Several people have asked me why I chose to make Cosmology a live experience, what was in it for me.

There are several reasons: first of all, I really believe that sharing a live moment with other people creates a special emotion. It’s like watching the downhill ski competition at the Olympics: it’s not the same thing to see the race live or to see it recorded.

But live is also practical. For instance it’s easier to organize a live classical concert than making a record in a studio. For a live concert, musicians rehearse in the afternoon and play in the evening, but if you want to make a record, you have to book a studio, work on a recording plan, do several takes to get a really good quality, edit, remix. Errors and glitches are not acceptable in a recording. In a real time performances glitches are only an instant, a momentum. In a way, in a live performance, the audience is expecting inaccuracies, that’s what makes us feel alive.

Also, something that is often overlooked in live performances is, they get better after each performance because we can rework or edit the piece.

Cosmogony was very different when we presented it in Singapore in May 2021 than the version we showed at Sundance New Frontier in 2022. The show had the same length, the music was the same, but we made several crucial changes, correcting the choreography, the camera movements, better defining the performers’ movements. We changed some of the avatars, gave them blinking eyes that we didn’t have before. Live means that the piece is always evolving until it finds its definitive format. So every live show is slightly different.

On the contrary WOMB, which is a 3D film, has errors that I notice every time I watch it and that I will never be able to correct. I will have to live with them until my last day on this earth! (laughs). With Cosmogony we modified the work until we reached, I think, its final format. That’s why I think the last performance at Sundance was much better than the first one in Singapore. A live performance is more natural for a choreographer than a pre-recorded one because the piece can always be modified.

Virtual Crossing and other projects

G. J. – As creators, we are beginning to understand the value of the digital in real time as a tool for creation and collaboration. That’s why a collaborative project like Virtual Crossings was born: it’s about bringing together groups of digital artists from different parts of the world to work together remotely but simultaneously. So far we’ve done two collaborations with Buenos Aires and Melbourne. For a few weeks we have been working every day remotely, collaboratively and in real time. It was so interesting to see how we developed the daily routine of remote collaboration, how we connected every day with our partners literally on the other side of the world meeting across time zones, feeling the new normal through our digital bones. We experienced new sensations like what I call digital embodiment, having a real physical experience between distant digital bodies.

We soon felt the need to be active in the making of a digital ecosystem for digital creation from the point of view of the performing arts. Our Studios44/MocapLab studio in Geneva city center is now equipped with 42 Qualisys infrared motion capture cameras.

We invite artists and companies in residence to experiment with our equipment, the idea being to work without the constraints, and costs, of a commercial motion capture studio. Our experience showed us that motion capture must be investigated in movement. Cleaning mocap data is very expensive, experimenting with time inside the mocap space can save a lot of expense in post-production. Every mocap system has its own shortcomings. Optical, accelerometers suits, point cloud mocap: creators have to find the most suitable mocap system for their project while movers need time to understand their specificity and there are many solutions that can be found in movement. As I often say, we must find artistic solution to solve technical problems.

One of our first company in residence is Instituto Stocos from Madrid: choreographer Muriel Romero, composer Pablo Palacios and digital artist Daniel Bisig are investigating motion capture for sound.

The Geneva based If Company is investigating a real time theatre play and we will produce a digital 2D film for the fabulous dancer and choreographer Agathe Djokam from Cameroon.

Our company is currently working with artist Thomas Ott, an incredible Swiss illustrator. This VR piece will be set in an undereorld motel on a lost highway.

All these projects by different artists have in common that they experiment with real time as a tool for creation.

On the challenges of video streaming

G. J. – The most difficult thing we had to work on with Cosmogony was the live video stream from our Geneva studio. You might think that a video stream is a very easy thing to include in a Unity project (Unity:3D game engine). You might think that sending motion capture across the world is more complicated than sending a video stream. It is not! Streaming, no matter what system you’re using, always has a 30 second delay. There’s no way around it.

Take La Comédie Virtuelle -live Show that we presented at the 77th Venice Film Festival: in this piece of five dancers, three are in Geneva, one is in Bangalore and one in Melbourne and they all dance together in the space of the virtual theatre, present in real time with the multi-user online audience.

To make the audience notice that the dancers are really live, we installed TV screens inside the VR space. Each virtual TV had a video stream from each of the physical locations. But the video delay created an artistic problem: the avatars would move and then 30 seconds later you would see the image on the screen move. People couldn’t understand it – it was counterintuitive to see the video moving after the the avatars moved. You would expect the opposite – we couldn’t find a solution. It was a big artistic problem, and it created doubts in the mind of the spectators.

Pierre-Igor Berthez, our developer, found a way around it, so we had no more delay and we could build the narrative for Cosmogony including this technical element. The difficulty with technology is to use it for what it can do and not what it promises. As a storyteller the main question I have to ask myself is: will the video delay be a problem for my audience’s understanding of this piece? Should I find an artistic solution to go around the technical problem? Sometimes a technical solution pops out of nowhere and instantly solves dead-end situations.

On the language of choreography

G. J. – As I said earlier, choreography is a language. Usually wordless, it carries a meaning but there is no narrative. The body of the dancers make it very concrete, but it is also very abstract, inventing movement and rhythmic sequences. Choreography is a suggestive language, it is the spectators who give meaning to the image they see. I am always surprised at how the audience picks up even the most abstract ideas in my pieces.

In Cosmogony a big part of the choreography is the movement of the cameras. It is like a long journey, a continuum, always moving from one place to another without cuts. The flying camera reminds us of our empty cities, like drones flying over the streets only populated by virtual chimeras, appearing like wild animals in our empty cities. And in a world of doubts, the Earth could be flat and our consumption rubbish is sucked into space.

One of the main choreographic mechanics of Cosmogony is the multiplication of the dancers. I only have three live dancers, but there are several dancers in the scene, apparently, and nothing is recorded. To do that, we actually multiply the mocap space! Two, three times. And then we turn it 45 degrees, for example, to create a space where different things seem to be happening: although it’s still symmetrical, of course, the varied angle allows me to show the dancers moving in different directions to the camera. Add that to the fact that I’m using different avatars – in size and appearance – and you don’t even realize they’re the same dancers anymore.

An in-depth look at the meanings of contemporary dance

G. J. – Contemporary dance is very different from other types of dance: first of all it is made by living artist and it lives only when performers and audience come together in a space. Most of the time a piece is a prototype, it has a life of 2, or 3 years, sometimes more, and it fades away from reality after the audience sees it. A dance piece is a momentum in time, space and movement that, like a particle physics experiment, contains everything possible before the spectator sees it in a fleeting state. The movement only exists in a fraction of time, the audience may forget it or remember it for a lifetime, but they usually do not get to see a dance piece twice.

Choreography is often an empirical, collaborative work between the choreographer and the performers and we always start with an empty space. We work with dancers, creative performers, who bring their creativity into the piece. As a choreographer I set the rules, I direct the quality of the movement, but the dancers find their own way to embody my instructions. A bit like a sports coach, but I am inventing a new game for each creation.

Both choreographers and dancers, but especially dancers, have to learn how to make the best use of the space available to them, and they can be very good at that. I heard that now, with the pandemic, a lot of dancers in the United States are working for the video game industry: it doesn’t surprise me, they are very precise in their movements. Dancers are not actors, they are not playing a character, they are themselves in action. Their emotion grows from their own movements, they live what they dance.

Contemporary theatre, performing art or live art are very similar to contemporary dance, and in these fields artistic creation is an empirical process with no predictions about the results. The piece grows as you go along.

Years ago I did a residency at CERN and I remember a question from a woman in the audience: she asked one of the physicists if they always found what they were looking for. And his answer was: no, we don’t, because if we did, we would not be researchers, we would be producers! A commercial production aims at a result, to laugh, cry, entertain, whereas we are experimenters guided by our research. The show is either profitable or it is not profitable. We are sustainable.

On the music in Cosmogony

G. J. – The music is by Tar Pond, a doom metal band whose lead singer is Thomas Ott, who happens to be the illustrator I will be working with. This is how we met, and the drummer, Markus Edelmann, is one of my best friends.

I chose their music specifically because Cosmogony is a very digital work and having analogue music seemed the right thing to do. The music is played with real instruments, sung with real voices, I understand it is a less obvious solution than going for a very techno-digital soundtrack. I wanted something edgier, more raw, so that there was a contrast between the music and the eerie psychedelic moments of the piece. In the performing arts you have a very wide range in terms of how you can combine elements – lighting, sound, performance, stillness, movement, etc. Music is immaterial and its presence or absence is very important in consolidating meaning in an abstract piece

Pushing the boundaries of dance using immersive technologies

G. J. –I feel that people from the performing arts can be relevant in the XR space. Out of fifteen works in the Sundance New Frontier 2022 lineup, two were live contemporary dance performances! And it’s a film festival! This was our third participation at Sundance and I am a choreographer, it is quite unusual for dance, an art form that today’s cinema does not really put in a central place. Think about it: when the film Suspiria came out, I read all the reviews and none of them mentioned the choreographer’s name. And it was a film about a dance company!

The XR space is a good space for us because it is open and looks at what we do, and can invite different approaches to the same thing. Suga’ (a/n read our interview with lead artist Valencia James) does the opposite of what we do: they use very accessible low-tech motion capture technology, we use very complex high-end technology. But there is so much potential between these two extremes and so much to do in the middle. For me it was remarkable to have two contemporary dancers and choreographers in the Sundance programme and it’s sad that the dance industry still lives in its own little bubble and does not seem to see how relevant this is. What’s happening is historically important for our field!

In fact, I think traditional dance looks at these kinds of live dance performances with a specific fear, the same fear that cinema might have towards VR: they are afraid that the technology will take the place of what is already there and suck up the little funding that is available. To me this is a ridiculous and historically inaccurate notion because a new media has never replaced another media. Cinema did not kill radio and television did not kill cinema.

Mapping the world of dancing in a 3D space

G. J. – Covid19 has given a boost to the kind of technology we are interested in. The different pieces we did with connection and distance, our ability to invite any motion capture system into a 3D space, from anywhere in the world, is a huge step for dance. We can connect without the limitation of geographical boundaries and air travel, it opens up a whole new range of possible remote collaborations.

Today, a team of 7-8 artists and technicians can create their own technology for remote performances in full autonomy. We can bring dancers and audiences together remotely to experience a live piece even if we are all in different countries… there is so much we can do today compared to what we could do before!

This is a global new reality. Artists like Valencia James and her Volumetric Tool box project, or Clemence Debaig, who experiments with connecting dancers at a distance between London and New York, publishing the research live on Twitch. Zelia ZZ TAN, who is a gifted Hong Kong dancer I met on Instagram. I’ve invited her to collaborate with us, even though we’ve never met in real life. Carol Brown and her VCA Dance in Melbourne have a huge optical motion capture studio, Diya Naidu in Bangalore has her own Rokoko suit and our lead dancer Susana Panadés Diaz is integrating her own dancing with the animations and worlds she’s building in Blender and Unity.

There’s also a growing community of dancers within VR Chat. At Sundance I watched We met in virtual reality (a/n here’s our interview with director Joe Hunting), and one of the most interesting parts was about people dancing in VR Chat. One of the characters, Dust Bunny is a dance teacher and regularly offers lessons in all kinds of dances within the virtual environment. There is also a remote hip hop battle. Dancers are working on how to make better use of their not so perfect mocap system!

I have an intuition that the performing arts, perhaps more so than cinema, hold many of the keys to unlocking innovative digital pieces. Performers are the masters of real time. And in surreal times, real time is what we need.

Find out more about Cie Gilles Jobin on the official website and about the motion capture of Cosmogony at this link.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.