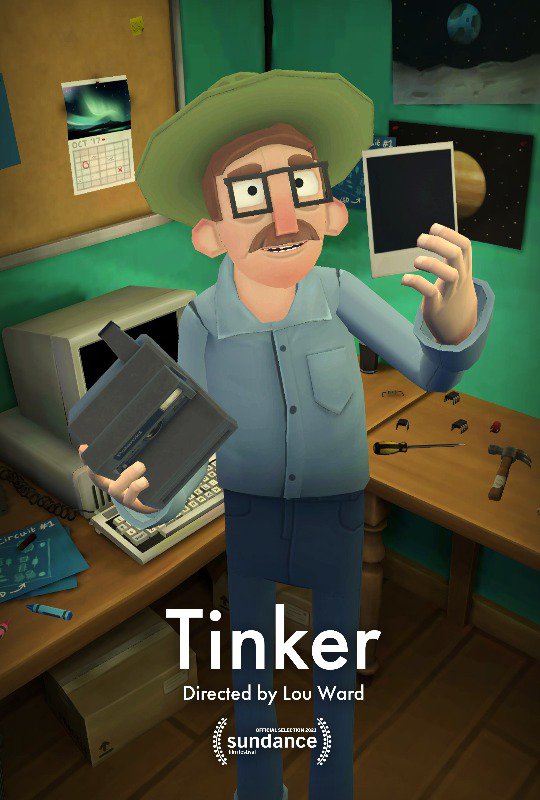

In the lineup of the New Frontier section at Sundance Film Festival, TINKER is an un unscripted and interactive, virtual reality theatre performance about Alzheimer’s, relationships and building memories together.

The moment that really marks the beginning of the new year, for every XR enthusiast, is the Sundance Film Festival.

Their New Frontier section is the ultimate place to discover some of the immersive experiences that will dominate the festival circuit in the months to come. The lineup announcement is eagerly awaited by all who want to know what the future holds.

And this announcement came just today: a list of 14 works – a recap can be found here – and among them, one that caught my attention long before it became part of this important festival.

This work is Tinker and I came across it months ago, while looking for immersive pieces that not only reflected on relevant psychological dynamics, but did so in a narrative way. Pieces that could have concrete applications outside of the cultural field, but at the same time approach their contents through a beautiful story.

Which is something that – I have learned – can have a much bigger impact than just a scientific approach.

Tinker is “an unscripted and interactive, virtual reality theatre performance” directed by Lou Ward and produced by Tinker Studio, a diverse collective of technologists and creatives whose mission is to make social mixed reality experiences of impact.

It is the story of a grandchild coping with his grandad’s Alzheimer’s disease and the effects on their relationship of the slow-progressing loss of the memories they created together.

Having had Alzheimer’s cases in the family, this is a very sensitive subject for me, and I always end up crying my eyes out whenever I find works that talk about it. Cosmos Within Us did it (here’s our interview with its director Tupac Martir), but Tinker’s approach is different.

First of all, because of the different perspective it chooses: in Cosmos Within Us you were the old man losing his memory. Here you are the grandchild, and the one who finds himself facing the pain that comes with having someone you care about go through something like this.

Secondly, because Tinker is inspired by a true story. The one of Lou Ward himself, who lost his grandfather to Alzheimer’s. And it is also the story of all of us who have had similar cases in their family and of our common need to find something good to cope with it all, despite the sufference it brings.

But Tinker – and this might be what really struck me when I talked with Lou about it – is not a tragic work. Somehow, it feels like the opposite of a tragic work.

It is a reflection on something that is far more important than loss, or sadness, or illness.

It is a piece that celebrates care and love and that teaches how to cherish the past to find strength for the future. To understand that memories are never truly lost, even when they are forgotten, because creating them was what shaped you and made you become who you are now. Something I clearly recognized in Lou, who created this piece to honor his time with his grandfather and their days of tinkering together.

I spent quite some time discussing the creative process of Tinker with Lou, with narrative, performance, and game designer Shimon Alkon – who’s also writer of the piece – and with creative producer Lara Bucarey.

Here’s what they told me about their work.

How it all started and how it changed

L. W. – I created Tinker because I was hoping it could help me and other people cope with loss. We started with a film based on a 2D animation, and then evolved into a VR experience. Initially, a developer friend of mine and I made it as a co-located work with an IMU sensor-based mocap technology. It was always in the plans to make a multi-user piece, but one where you could also physically touch the grandfather.

As time evolved and technology grew, our inputs for the users and the character of the grandfather changed a lot. To complicate things, IKinema was bought by Apple and all licenses were basically killed within a couple of weeks. So we had to restart the project and develop it in a different way, keeping the core of our experience intact.

We wanted it to be a story that people could relate to and that really talked about memories. All of that was maybe lost in previous iterations because we were focusing on using bleeding edge technology at the time. But in the end, what really mattered was to showcase our narrative and what neurodegenerative diseases do.

That’s also why we decided to work with an actor rather than AI. We wanted a different play every time and for every single user, one that spoke directly to you, and that was about the memories you created within the story and the things that you love. However, we worked on several innovations, such as facial controls within a virtual space rather than just a camera, creating preset emotions, controlling eyebrows and other nuances like that.

The other thing that has changed in recent years is that we have formalized our group into an indie collective studio and now we have a working framework that we apply to different projects that all aim to have some kind of social impact.

Learning to interact with the world of Tinker

S. A. – We are working with emerging technologies… or rather, re-emerging technologies, because people are learning now how to use them. Some have never tried VR, others are not familiar with interactive narratives and so you need to find ways to guide them through it. While working on Tinker, we looked at the experience and asked ourselves: how can we provide a tutorial in the context of the experience? How can we integrate technology and interaction with the narrative?

The story itself, however, is a natural progression: you start as a child in the crib and you don’t have much agency there. You can interact with a few things but, as the scenes progress, your circle of influence expands, people come in, you create relationships and you’re able to interact more and more.

Figuratively, it is like growing up in the VR world, and that is exactly what you are also doing as the main character of the story. And your grandfather is the one who shows you, at first, how the world works; something that makes sense thematically but also offers us the chance to find an integrated way to guide people in the experience.

And when you have learnt – and you have grown up – then things change and you are the one who needs to take care of that someone in your life, who now needs to be guided by you.

Growing up and forming memories in VR

L. W. – In a lot of our pieces we use scale, and it’s something that is particularly significant in Tinker. You start in a crib, and everything is bigger than you, but eventually you’ll be the height of your grandfather: you get taller and the room feels smaller.

All the objects around you acquire a specific relevance: your grandfather teaches you how to interact with them, so you form cognitive memories of them. And at some point the roles reverse and you are the one who has to take care of him.

When we thought of this experience, we really wanted to convey this growing curve. It is really hard to showcase memories, so we created five main scenes that show different moments of our life and, with them, your progression within the story.

Then we added transition scenes that are really sound-driven and helped us convey the idea of intervening years, creating a sense of time passing by.

S. A. – In a way it was like working with people’s memories… cross-culturally, I believe a lot of people have this kind of eternal moments in their lives, touchstones in a person’s life, and that is what our main scenes represent.

Making it personal… through a theatrical performance

L. B. – Tinker is personalized for every participant. There is a discussion between the participant and performer prior to starting the experience which allows the performer to collect information from the participant and then infuse it throughout the course of the unscripted narrative experience, much like a professional improvisational actor would acquire information from the audience prior to starting their performance.

Elements like knowing your name, gender identity, etc. create a unique experience that’s tailor made for you, and connect you closer to the story.

The participant can also choose the race of their avatar because we wanted to be mindful of not only personalizing the narrative, but making the participant feel comfortable and the content inclusive.

S. A. – The story is also personalized. Different works have different degrees of improvisation: how much do they let the participant influence and effectively change the experience?

As Lara said, we are really trying to create a Tinker that is unique to you, but we are also working on the degree to which you influence the story itself, which is more significant than in other pieces.

Our improvisational performer, Randy Dixon, is a World Class Performer and he makes every experience of Tinker your own experience. He’s able to respond to everything you put in the work and really integrate it within the narrative, making it seem as if it has been written, when in fact it is totally improvised.

And indeed, one of the things I advocated in this project was not to write the whole story, but to let the performance rehearsal process drive the creation of the experience. Integrating live performance into a virtual environment, a real person into a virtual character makes for the trippiest VR experience and is what puts Lou’s work on the leading edge.

L. B. – In Randy’s arsenal of talents as a world-class professional improvisational performer, he has helped train doctors and healthcare professionals using role playing techniques to simulate patient scenarios in hospitals.

Randy’s essential understanding of Alzheimer’s disease and ability to portray it in a delicate and effective way allows participants to better understand the nature of neurodegenerative disease and augment the value of their perception through embodiment.

Social impact of Tinker

L. W. – This work showcases what it’s like to lose someone in any capacity, and what I’m really looking forward to is building empathy for this situation while creating memories together in the scenarios of this work. Something that can allow people to reflect on these issues after the virtual experience is over.

We really want to push Tinker forward as a sort of empathetic training, to give people a realistic idea of what happens in certain situations, but in a narrative form. We are trying to put narrative and teaching at the forefront of what we are doing and we’re also pushing Tinker towards qualitative research.

For example, you are talking with a person with a neurodegenerative disease like Alzheimer’s. What is it like? We could show the progression of this conversation using our work and its different scenarios.

Currently, the experience that we are working on gives you a whole lifetime of memories and a longer performance, but I think that the evolution of that is to build shorter scenarios for specific situations.

In the longer term, what I’d like is for people to reflect upon their own loss and go home being able to talk about it. About what they are feeling, so to process what happened.

It’s therapeutic to work on something that allows you to make an impact and to maybe remind people that time really is a precious thing.

Tinker will be at the Sundance Film Festival, which will take place between January 28 and Fe

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.