It is always a great moment in our immersive year to meet Mark Atkin, director and producer at Crossover Labs and curator of Electric Dreams Festival of Immersive Storytelling and CPH:DOX Inter:Active. With Electric Dreams recently concluded and CPH:DOX Inter:Active just around the corner, we caught up with him to talk about the new projects and how the organisation of these two exciting events went and is going.

Cover: THE UNCENSORED LIBRARY (Reporters Without Borders, Germany, 2020)

On the connection between producing and curating festivals

AGNESE – Here we go again, Mark! I know this is a very hectic time for you…. Electric Dreams, which just wrapped up in Adelaide, Australia – an exciting edition!, then CPH:DOX and related conferences in March…but there are also other projects you have been working on as a producer recently: Arcadia Live at the Barbican, Consensus Gentium at SXSW, Elsewhere in India at Roundhouse, London. How does it feel to be involved in all these different things?

MARK ATKIN – In some ways, everything is connected. The fact that we produce works allows us to better understand the needs of producers and creators when they come to our festivals, because we are now also in their position. We know what they need in terms of funding, because we had the same experience! It’s incredibly useful, as are the workshops and laboratories we have been organizing.

M. A. – In terms of productions, we made a series of nine films with live-performances. They’re not immersive in the sense of being in XR, but if we consider them in terms of immersive entertainment, they are certainly more than watching a film, because they are live. The most recent of these works is Arcadia, featuring folk singer Lisa Knapp, which deals with the problems associated with severing your ties with the land. The music is by Portishead’s Adrian Utley and Goldfrapp’s Will Gregory and it’s going to be performed live at the Barbican, a huge venue and one of my favourites in the world, here in March. I’m really looking forward to it!

M. A. – Then we have two more pieces lined up. There will be a festival called Futures at the Roundhouse, a music venue in Camden, London. It’s called Elsewhere in India and is both a live performance and a video game experience. In March we will also present a work by Karen Palmer, Consensus Gentium, at South by Southwest.

A. – What is it about?

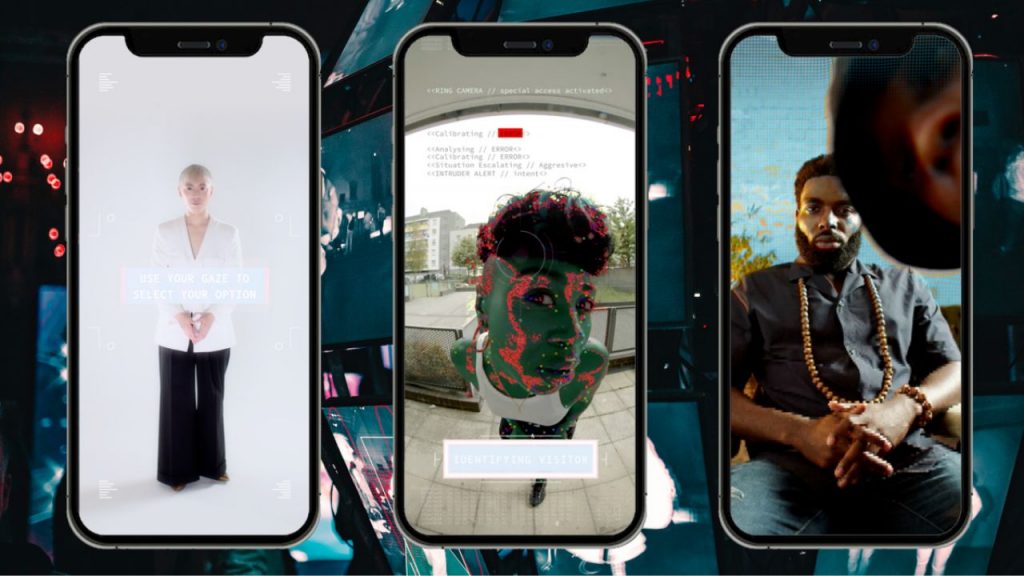

M. A. – Consensus Gentium is an interactive film that, using eye-tracking technology, imagines a future scenario in which, with your phone and the information you input, you will have to prove that you are a law-abiding citizen in order to access certain citizenship rights.

The work takes you through a dystopian scenario based on what is already happening in China today. It looks at some of the concerns we might have about technologies like these (eye tracking and facial tracking) and their possible consequences. I think that from Karen’s perspective, it is particularly relevant to see their use through the prism of the experience of being black, and how the black community responds to these technologies. It’s an activist piece that can have different narrative outcomes, depending on how you extend your focus into the work.

A. – You also mentioned Elsewhere in India…

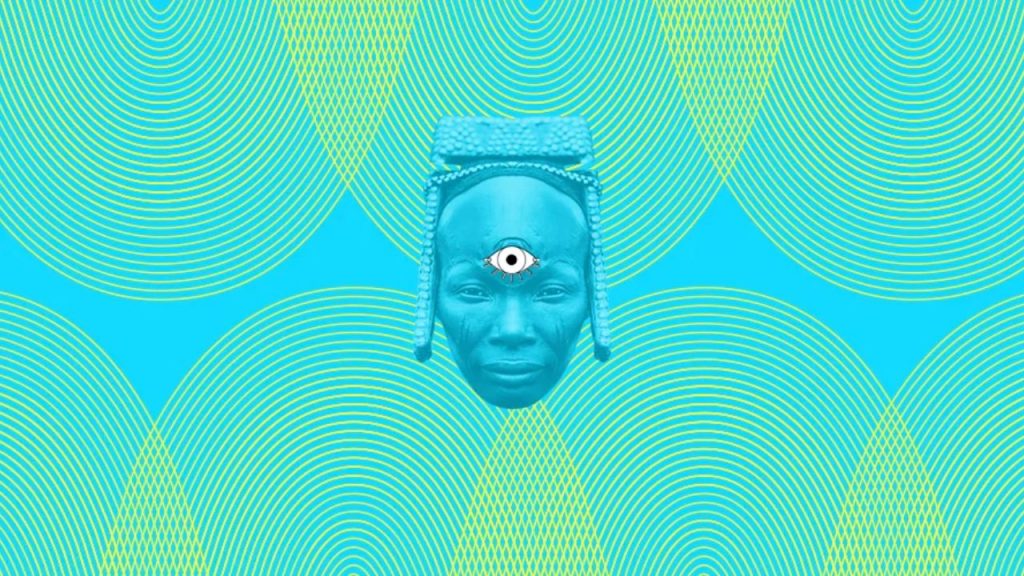

M. A. – Elsewhere in India is a live performance based on the traditional South Indian dance and music but it is also a futuristic piece set in 2079. It looks at the work of a cultural cyborg, Meenakshi, who is unemployed because people have lost interest in what she is interested in. But she continues to scan the world for artefacts and information about South Indian dance and music… and, surprisingly, most of the information about it can be found in collections in the UK! Eventually, she discovers two characters, Murthovic and Thiruda, and starts with them a journey of self-discovery and space exploration.

Elsewhere in India is both a computer game and a live performance, in which dancers and musicians interact with the characters in the 3D world of the game. We are actually scanning artefacts, objects, etc. from these collections in the UK to include them as digital assets in the game and the live experience.

This is a process we have called ‘digital repatriation of cultural heritage’, which is part of the current debate on whether museum collections should be returned to their country of origin and place of provenance.

We are engaging in this discussion in a playful and non-confrontational manner, but people will still have to think about it.

It also uses AI on the archive material to reinvent and reimagine Indian cultural development and to image an ethical roll-out of AI technologies in the Global South.

Lastly, we are working on Toguna together with an artist of African descent, Pierre-Christophe Gam (a/n Toguna won the Unity for Humanity Award in 2022). A toguna is a makeshift shelter where the Dogon people of Mali gather to discuss issues of wellbeing for the community. Pierre-Christophe reads the toguna as a kind of metaphor, and has created a Metaverse space, but also a physical space, where all people can come together to share their positive dreams about the future. The use of digital technology to build these spaces allows us to incorporate these dreams into the architecture of the space itself. Thus, the space will change according to people’s dreams. He has already started this process in the physical spaces and now we have built the metaverse world that reflects the dreams of a life lived more closely with nature and spirituality and love, etc. People can now enter this this world and continue the process of dreaming a better future together.

“Exploring the art of immersive storytelling”: conferences at Electric Dreams

A. – So many ways to imagine immersion…

M. A. – Absolutely. I don’t know if you’ve read Frank Rose’s books, but he wrote The Art of Immersion, where he defines immersion as the process of losing yourself in imaginary worlds created by someone else, so that you don’t even think about whether you are there or not. You’re simply… there. You start to inhabit that world. That is the true meaning of immersion.

AI is becoming another tool for artists, and it could open up an era of creative expansion. It reminds me of the days when photography was first invented. People thought it was the end of painting. But what actually happened was that painting changed in the most extraordinary ways and became much more interesting than before. I suspect that is what will happen now with artificial intelligence.

– Mark Atkin

A. – I noticed that you reflected a little on this theme in the series of conferences at Electric Dreams. What can you tell us about them?

M. A. – Electric Dreams is a mini-festival within the larger Adelaide Fringe Festival. We’ve always had conferences as part of it, and each of those conferences is an exploration of the art of immersive storytelling. We discuss technology and how it can become a useful tool for artists… how it can allow them to express themselves in interesting ways, but also engage the audience in ways that other media cannot. The overall idea behind this year’s conference, and one that is very close to my heart right now, was that games are changing absolutely everything. Many of the works that we presented at Electric Dreams, but that will also be at CPH:Dox, are built in a game engine.

It’s inevitable, when you think about it, that games are the defining – and the most popular – media of the 21st century. No wonder artists are looking at the way games are made to express themselves. We talked about this and of course also about AI, in particular AI and creativity: AI is becoming another tool for artists, and it could open up an era of creative expansion. It reminds me of the days when photography was first invented. People thought it was the end of painting. But what actually happened was that painting changed in the most extraordinary ways and became much more interesting than before. I suspect that is what will happen now with artificial intelligence. But the direction we take is also an ethical question and that is something we want to analyse.

For example, one of the panel discussions was “Decolonizing virtual spaces”. Avinash Kumar (aka Thiruda) of the company Quicksand is working at Elsewhere in India, one of the works we mentioned earlier. He designed this game with one question in mind: how can we decolonize video games that are being created? And indeed, Elsewhere in India is very “Indian” in its conception, in its creation. A really unique kind of a game.

At the conference we also had a fantastic Torres Strait Islander woman, Dr Vanessa Lee-AhMat, from Black Lorikeet, who is a cultural broker: she’s very keen to make sure that indigenous people are properly represented in the metaverse. She wants their culture to be valued rather than appropriated. Violeta Ayala, director of Prison X, which she developed on the CPH:LAB, joined us as well. She was recently in Bolivia to present a feminist workshop that looked incredible. I was thrilled to see her again!

Jamie Perera, musician and composer, also a former CPH:LAB participant, was also at the conference. He is working on sonifying data: he takes data points and turns them into musical notes in order to produce different stories. For instance, he used climate data to tell the story of a dying planet in a performance piece called Anthropocene in C major, which is in the lineup of Electric Dreams. He’s British, but his heritage is part Sri Lankan and part Malaysian so in his works he has thought a lot about how language is colonised and represents colonial thinking, and how sometimes words fail us, especially as composers. He talked a bit about this during the conference. But we also had other interesting sessions on spatial storytelling and technology-driven storytelling.

Electric Dreams: the immersive line-up

A. – What were the other works of the lineup of Electric Dreams?

M. A. – The lineup featured several pieces that use technology in interesting ways, sometimes very low-tech ways, while still creating great stories. Take Work.txt: there are no actors in the piece and no actual performance… the audience itself is the actor! There’s a printer and a mic on stage and it’s just incredibly fun to take our roles and figure out what we have to do and who’s going to do something next. It’s brilliantly written, it’s essentially about the future of work and it uses a very old technology in a very clever way.

Another piece about work was Temping: again, there are no actors, but it is still an immersive play. In it, you are a temp who joins this cruddy office somewhere, and you work out what you’re supposed to be doing entirely through answerphone messages and Excel spreadsheets. At first you work on the usual boring things you get to do in an office space, but then you realize what this firm actually does and what you are supposed to be doing, and the horrible story behind corporation is just so brilliant!

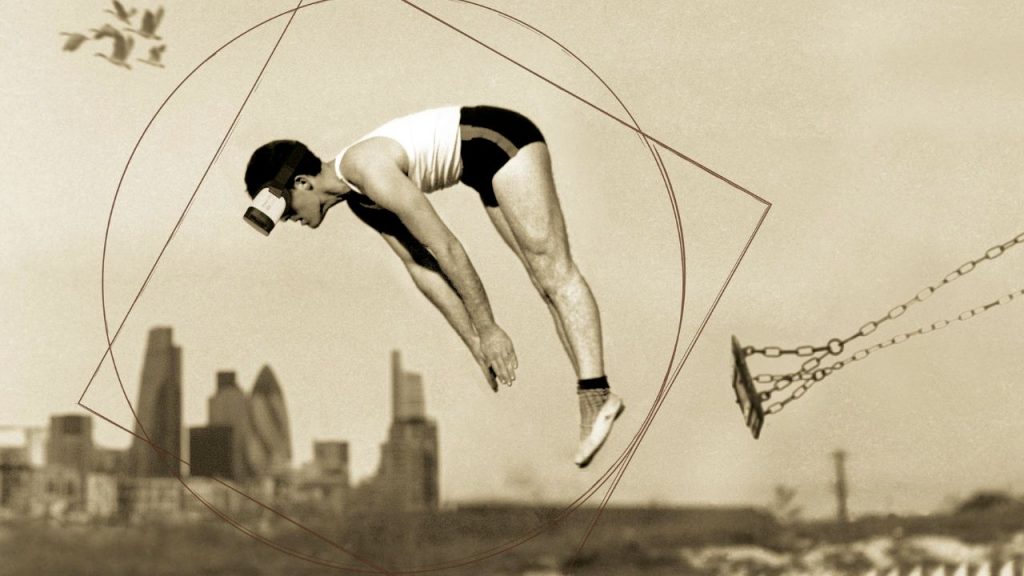

Another piece we hosted was VR Swings: Volo – Dreams of Flight by Studio Go Go and Brendan Walker, the “thrill engineer”. We had a whole set of swings. You put on the goggles, and start moving on them. Each of the experiences represents a different Leonardo da Vinci’s flying machine and you operate the flying machine by swinging on the swing. It’s like a fun ride. People loved it and bought tickets for it, which is great. But it’s also a way to discuss science and engineering, which is very informative.

I have already mentioned Elsewhere In India, which was also in Adelaide in a sort of half physical, half digital performance. Splitting it into these two parts felt like a step to bring the physical world and digital world of the metaverse closer together. Finally, there was another performance called Torrent. It was incredibly beautiful. It’s made in the game engine and features live performance, motion capture techniques, dance and poetry by the incredible indigenous poet Ali Cobby Eckermann. The movements in front of the screens turn the dancing bodies into dust and water. It is not a VR work per se, but uses these technologies to create a live theatrical dance performance.

Working with emerging artists at CPH:LAB

A. – Curating the festivals, but above all the CPH:LAB, gives you the opportunity to find and work with emerging talents of the immersive field. Could you tell us something more about this aspect of your work?

M. A. – The CPH:LAB is fundamental. It focuses on people working with immersion in completely different ways and is designed to allow artists to experiment. We always ask participants to do something completely new… and it is not necessarily new to the world, but it is definitely new to them! Everyone moves completely out of their comfort zone and creates work and art using technology in a way that is very interesting to them.

We have nine projects coming through that program and we started working with them in September 2022. We develop these concepts and then bring them to CPH:DOX, where they are presented in a conference format that we call a Symposium. It is attended by the workshop cohort, the artists presenting works in the exhibition and other invited guests, and together they are asked to discuss what the cultural landscape will be from these projects/prototypes as they enter the world and people begin to contribute to them. So, we are always looking to the future and where we are headed.

CPH:DOX’ INTER:ACTIVE line-up in alphabetical order:

- AQUAPHOBIA by Jakob Kudsk Steensen, USA, 2023, Game, World Premiere ATUEL by Matajuegos, Argentina, 2022, Game

- BLACKTRANSARCHIVE.COM/WE ARE HERE BECAUSE OF THOSE THAT ARE NOT by Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, UK/Germany, 2020, Game

- CONSENSUS GENTIUM by Karen Palmer, UK, 2023, Interactive film, European Premiere

- ENT- (MANY PATHS VERSION) by Libby Heaney, UK, 2022, Game HE FUCKED THE GIRL OUT OF ME by Taylor McCue, USA, 2022, Game IN THE MIST by Chou Tung-Yen, Taiwan, 2020, VR

- I TOOK A LETHAL DOSE OF HERBS, Yvette Granata, USA, 2023, VR, World Premiere

- LOCAL BINARIES by Lauren Moffatt, Germany, Spain, Denmark, 2022, AR, International Premiere

- MLK: NOW IS THE TIME by Limbert Fabian, USA, 2023, VR, European Premiere PARALLAX by Akihiko Taniguchi, Japan, 2021, Game

- PSYCHOPLANKTON by Superflex, Denmark, 2022, VR

- THE JUNGLE PEOPLE by Eddie Wong, Malaysia, 2022, Digital video

- THE TELL TALE ROOMS by Andrew & Eden Kötting, UK, 2022, VR, European Premiere

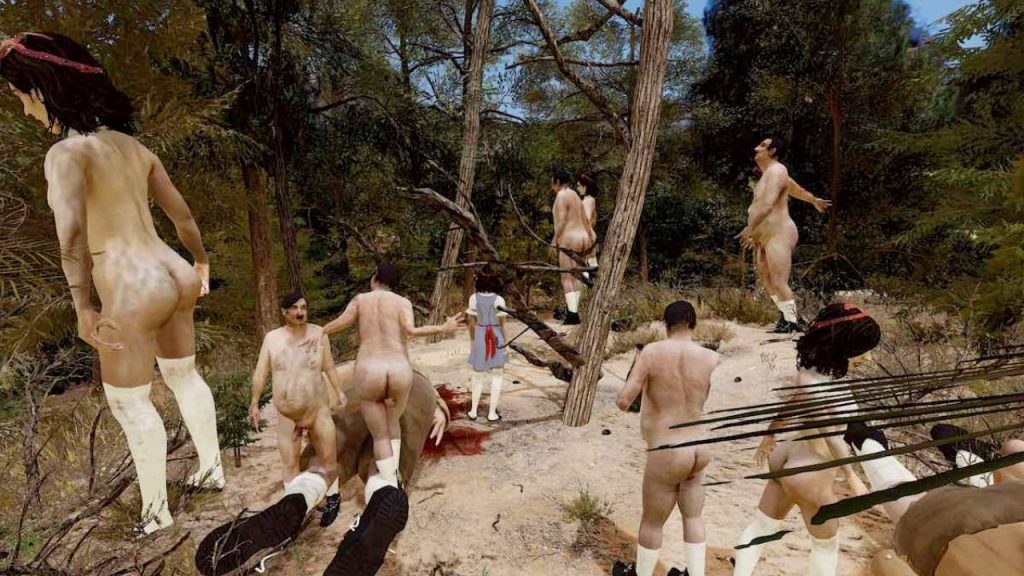

- THE UNCENSORED LIBRARY by Reporters Without Borders, Germany, 2020, Game THE ZIZI SHOW by Jake Elwes, UK, 2020, Interactive performance ZIZI: QUEERING THE DATASET by Jake Elwes, UK, 2019, Digital video

INTER:ACTIVE Live Specials line-up:

- AS MINE EXACTLY by Charlie Shackleton, UK, March 18 – 26, 30 min individual slots – Kunsthal Charlottenborg

- HIVEMIND with Danielle Bathwaite-Shirley in association with Trust and Serpentine’s R&D Platform. UK/Germany, March 19, 16:00 – Mezzaninen, Kunsthal Charlottenborg

- ZIZI & ME by Jake Elwes and Me the Drag Queen, March 19, 17:30 – Mezzaninen, Kunsthal Charlottenborg

This year’s Symposium will also address the rise of the game engine, why it is such an important tool for artists and how it will influence the steps we take towards the metaverse.

If you look at the interactive work we present in the exhibition, practically everything is created with a game engine. But it is also created by neurodiverse, non-binary, queer artists…. by minorities in general. If the metaverse continued to be built only by international companies, mostly based in the US, or by authoritarian governments, like China, would any of these artists be part of it? I think the answer would be no, and we do not want that to happen! What steps should we take now to create an inclusive and open metaverse? This is what we will reflect on.

But the Symposium is also a way to discuss the works created during the CPH:LAB, to imagine how they might land in the future, and to engage participants in discussion with other artists. It is not exactly a pitch but a sort of embedding of the presentation in a discussion with other experts on the future of artistic creation in the coming years. There is an activist intent behind it: we have to start joining forces now, to make sure we don’t make the same mistakes we made with the Internet, thinking it was going to be a fantastic open space and then discovering that it is actually a bit of a nightmare. We have to learn from the past, but we have to start working on it now to be successful. Afterwards, the artists all gather at what we call a ‘prototype party’. It is a networking event where people can meet other artists and experience what they have built. Finally, the next day there is the possibility of having one-to-one meetings, more like art market meetings.

Reflecting on the metaverse: a bigger, in-person edition of CPH:DOX Inter:Active

A. – The CPH:DOX Inter:Active came back with a fantastic in-person edition last year. What can we expect from this new edition?

M. A. – This time, almost all the works can be admired in Kunsthal Charlottenborg art gallery, which is the operational centre of CPH:DOX. Only one piece occupies a different venue. But the whole concept of this festival is different from last year. In 2022 we had a small number of rather large installations, because we were so excited to break out of the confines of the screens and online presence we were stuck with in previous editions. But now we’re moving on from that and there is a lot going on. The full programme lineup was recently announced. The whole idea of the metaverse (good for artists? Inclusive?) that I mentioned earlier is behind the exhibition, titled “Breaking the code“. We’re looking at artists who are using use digital ones and zeros to explore the messiness of nature and humanity beyond binary definitions. I like the way this subverts the neat, logical patterns that can be found in the digital world to explore something that’s inherently disordered and entangled. This is why we have so many works by neurodiverse artists, non-binary creators, and so on.

M. A. – The first group of experiences will look at the relationship between AI and power. Some artists have been using AI to comment on the creative collaboration that can be had with artificial intelligence, but also on its failings, the way artificial intelligence has been trained, the way this technology is rapidly finding its place alongside us in society and as a tool for creatives. Then there is a second area dedicated to immersive works, both in AR and VR, focusing on neurodiversity and activism.

The third area is our twisted games arcade full of games made by artists and documentary storytellers, all using interactivity to draw us deeper into the subjects they are exploring.

Finally, in the last room you will find a joyful paradise, built in game engine, which will feel like a celebration after dealing with rather heavy concepts in the previous rooms. There are many artists and I’m extremely proud of the program we have built!

On the challenges (and potential) of XR

A. – One last question for you, Mark. Which aspects of immersion and technology are you most excited about at the moment and which ones do you find most problematic?

M. R. – For a while we have all been very concerned about funding. We still have practically no funds dedicated to immersive works. Yet, many productions are made, so evidently people find ways around the problem. But the real issue is what happens afterwards: there are no distribution channels. I think this is the biggest problem we are facing in this sector today and it needs structural intervention to be solved.

My answer – which I don’t know how many share – is to rethink the cinemas that many people no longer frequent. Keep one screen for films and turn the other rooms into mixed spaces where immersive works can be shown. I don’t think people will watch immersive works from home. We are still at the stage where people want to go out and have these experiences with friends. It is an inherently social activity.

So, let’s create spaces where people can go in a group, hang out at the bar and talk about the work after experiencing it. This is what we need… but there are very few venues like this in the world.

As an extension of that, I think one of the things I am most excited about in terms of immersive entertainment are experiences on a more theatrical scale. Since you want to spend money on an immersive experience, it has to be more than just an experience watched through a headset. It has to have a lot more around it. A bit like Torrent: it is an amazing technology, but it also takes place in a theatre environment. It is quite expensive to get the right screens to project it at the time, so all in all the whole thing is quite costly. But this also means that you can only experience it if you buy a ticket to go to that specific venue. And therein lies the value.

Find out more about the recent Electric Dreams festival and the conferences it hosted at the official website.

As for CPH:DOX, see you in Copenhagen from 15 to 26 March 2023! XRMust will, however, be back to tell you about the impressive line-up in the coming days.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.