Every year, on November 11, the world celebrates the end of the First World War. Last year XRMust dedicated an article to its 100th anniversary, interviewing Sébastian Tixador, director of the powerful 11.11.18.

In November 2019 we want to remember those tragic years and their ending talking about another installation that caught our interest at the Venice Film Festival in 2018. An installation that, two years later, is still, to me, one of the most fascinating works in VR about the WWI.

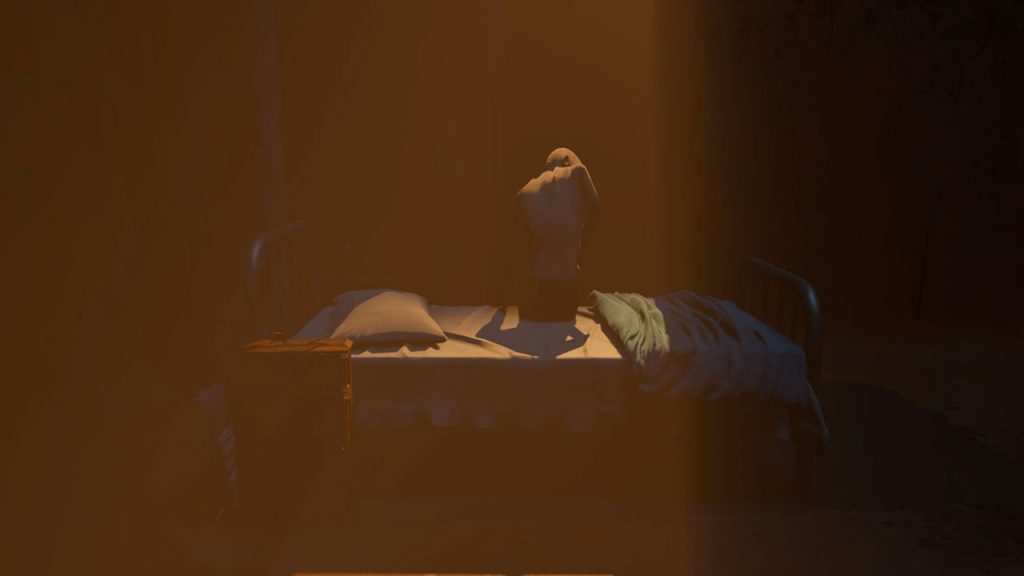

THE UNKNOWN PATIENT is a work directed by Michael Beets and produced by Unwritten Endings/VRTOV: In 1916 a man was found wandering the streets of London in an Australian soldier’s uniform. He did not know who he was. He was deemed unfit for service, labelled a ‘deserter’, and sent to a Mental Asylum in Sydney where he spent 12 years without an identity: lost and forgotten. How he came to be found is the remarkable true story of THE UNKNOWN PATIENT.

I was mesmerized by this production not only because of the story it tells, but also because of the work that Michael Beets, Richard Healy (concept artist and painter) and the whole group who worked at its creation did. A work that was able to convey, in an almost physical way – incredible effective from a psychological point of view – the concept of amnesia and therefore, the consequences of that horrible conflict.

We discussed with Michael Beets the creative process that led to this installation.

VR and history: the story behind THE UNKNOWN PATIENT

Michael Beets – When we put on a headset and step into virtual worlds- especially interactive experiences- we immediately ask ourselves ‘Who am I? and what is my role in this story?’. This question of identity is an important question and throughline for our story – the audience must discover who they are, or rather who ‘The Unknown Patient’ is. The story really is an unbelievable true story and for the audience to go on that journey of discovery as the patient, seemed like a logical choice that played best into the possibilities that VR offers.

M. B. – We had some unbelievable reactions from the audience: from teary eyes, to genuinely frightened “I can’t watch this” moments. One of the most powerful moments was at the Venice Film Festival where a gentleman took off the headset crying and confided in how his grandfather was a POW (a/n prisoner of war) and made him think about how his family would have felt during that time.

M. B. – This story works on many levels because it is both simultaneously a tragic and uplifting story. On one hand we have a nation that was still very much recovering, ten years on, from the effects of World War One. In Australia alone, 20,000 men never came home, and for many families they were missing, not dead, and I think there is a clear distinction in that healing process. So when, ten years on, the country heard that there was a man alive who might be their son, brother, father or husband- the story spread like wildfire.

M. B. – The size of the story itself, from newspapers across the country, paints a picture of hope and desperation as thousands of families came to the Callan Park Hospital to claim him as their own. When I was reading this I couldn’t help but think of all those people who had no closure, and then suddenly this wound – still healing – was opened once again. I couldn’t help but think how tragic it must have been to realise that he wasn’t theirs, and then for all those families to return home- to relive all that pain. Luckily, though, for one family that wasn’t true.

A new way to approach the creative process

M. B. – I’d say (the biggest challenge was) getting my hands dirty with the tools. I had to really dive in deep with the developers and learn how to use Unity. If anything, I’d say that at the start I approached it much like I would a film. So that the production was a streamlined process. However, once I started understanding the tools, the project began to shift quite immensely and because of that experimentation mid-way through, we found some great stuff.

M. B. – Two years on, I would say that my creative process has completely shifted. Now when I have an idea, I first experiment and test within Unity to see what the experience might feel like in a headset, and then once all that has been formed, we start building. I like to think of the way I work now like a theatre workshop where you play with rough ideas to form stronger narratives and then go off and write it.

The future

M. B. – I have just wrapped on an interactive project built for the Quest. It’s a project based on these old artefacts that they found directly below the building I’m working in; they’re building a subway. Basically, you pick up these artefacts and revisit these historical moments in Melbourne. I’ve also just shot a 16mm short film in Japan that will accompany an interactive film that is all about death rituals from around the world – I’m very excited about this project!

Find out more about THE UNKNOWN PATIENT at Michael Beets’ official website.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.