Prison X is an immersive Andean mythological play that, by working on representation, brings the user face-to-face with a different way of building stories and a culturally vibrant experience.

Representation in media is always something difficult to achieve, especially when it is done by “outside eyes.” In other words, by someone who doesn’t belong to the community that a particular media wants to talk about.

I’ve noticed this even as an Italian girl who spends too much time watching American blockbuster movies. Whenever I see a fellow Italian on the big screen, they are either eating pizza (accurate), portraying a very well-dressed Camorra / Mafia guy (not so very accurate, see Gomorra for more correct fashion references) or – and that’s worse – they are played by Spanish actors. They may even be good actors, but they definitely look and, above, talk differently from us.

It may not seem so from the outside but believe me: it takes exactly two seconds for someone like me to recognize when there’s fake Italianness in the air.

This, for me, is mostly amusing, but there’s something to say about it: my “community” has not been colonized. It has not been a scapegoat for social problems. Most of the complaints you hear about Italians…well, they come from the Italians themselves.

There are communities around the world that cannot say all this. People whose stories are mostly told by outside eyes that don’t do them justice because they don’t really capture their narrative, the way it flows and how these communities see and interpret the world.

Lisa Valencia-Svensson, Emmy award-winning documentary producer, effectively summarized this problem in her 2019 keynote addressed at Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Festival.

“When I have seen people like me represented in stories, I have rarely seen accurate representations of ourselves—just very damaging, negative, racist and sexist depictions. The inevitable and often subconscious result is that the perspectives of marginalized people are not seen as important, and a lifetime of taking in these messages does not naturally build up anyone’s self-worth […] By the very telling of our stories from our point of view, including our emotions in all their complexity, we are already working to shift the narrative at a deep cultural level” (x)

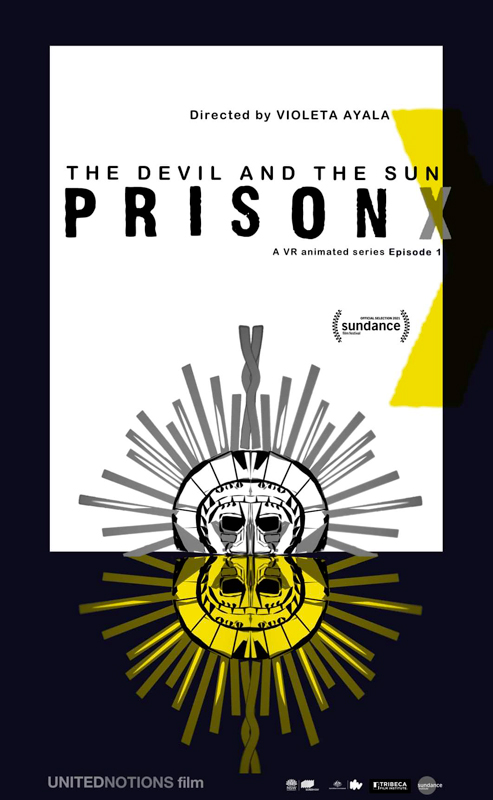

This keynote came back to me when I experienced Prison X – Chapter 1: the devil and the sun at the New Frontier section of the 2021 Sundance Film Festival.

Created by filmmaker and writer Violeta Ayala together with female Andean artists and POC programmers, illustrators and technologists, Prison X is a VR animated series set in San Sebastian Prison, Bolivia. It’s a work that leads the user in a mythological journey inside the dreams and nightmares of the Neo-Andean underworld.

“The eccentric deity The Jaguaress greets you at the velvet curtain gateway between theater and lived experience. She casts you as Inti, a young man who dreamed of being a drug lord but ended up in prison after his first job as a mule for la blanca. Prison X is an immersive Andean mythological play that sweeps you into a labyrinthine Bolivian prison, where you coexist with devils, saints, corrupt prison guards, and even a Western filmmaker” ( Sundance Film Festival – New Frontier catalogue)

This piece is permeated with the spirit of the world and the people it’s about, and that may be its greatest achievement and one of the purest things a work like this can achieve. From the characters – their identities, looks, even their shapes – to the design of the clothes, to the places we see and the weather we breathe in… everything belongs to a world that I have rarely seen and even more rarely heard told in this way.

We had a long chat with Prison X creator Violeta Ayala, with Roly Elias, sound designer and 3D illustrator, and with Alap Parikh, lead developer of the project. Here’s what they told us about the importance of representation and about the necessity of a new, different approach to stories and to technology.

Prison X is a thematically complex work. What can you tell us about it?

VIOLETA AYALA – Prison X is a very immersive interactive experience that will reach different people on different levels. You have so many layers to this story that it is difficult to predict what users will get from it: the younger ones often notice the environmental message, others the cultural elements. This layered approach exists mainly for two reasons. First of all, we are a very diverse team of creators, both in origins and backgrounds. We are from Bolivia, India, Germany, Australia… We have fashion designers, we have DJs, we have creative technologists like Alap. Roly is a sound engineer but he comes from live music. Completely different people with different approaches to the world.

But there’s another reason for it: I have a severe case of dyspraxia. I see everything in a very multi-layered way and I wanted to play with it and represent it in my piece. This is why Prison X is both a representation of how I see the world, but also of the Quechuan interpretation of its elements.

Why did you use virtual reality to tell this story?

V. A. – In 2010, we started shooting our documentary film Cocaine Prison inside San Sebastian Prison in Cochabamba, Bolivia. The project was successful, but I kept feeling a strong need to say something different about that place, something my camera could not capture.

Since I discovered VR, I watched many experiences, but I wasn’t really impressed with anything: I couldn’t understand why some artists were using VR to create what could have easily been made as a flat film. I wanted to do something different, but I was not sure VR was the right way. Then – it was about 2017 – I met Amaury La Burthe [a/n creator, with Arnaud Colinart, of Notes on Blindness: Into Darkness] and explained my doubts to him. He invited me to his studio and there I tried Tilt Brush for the first time. That’s when it all started to make sense, and I knew that was a path I could follow.

What happened, then?

V. A. – Me and a friend of mine, Bolivian artist Olivia Barron, created a small model of the prison where the story would have taken place. It was very architectural, and it just didn’t work. So, we used photogrammetry to bring it into Tilt Brush and started painting it all over. Different layers, assorted colors. That was the first step.

At the time I did not know much about this technology. My little cousin Camila Claros, who had just graduated in Robot Engineering, joined us to help us with Unity. And then we also started receiving grants and pitching the work at several events. I kept writing and writing, and people were criticizing my scripts because they were simple. But what I realized at the time was that over-complicated things didn’t work in VR. What I really needed was to marry interaction and immersion. Someone at a Sundance workshop told me this combination didn’t work… but I think we proved them wrong together.

ALAP PARIKH – We worked on this work part in 2019 and then again at the beginning of 2020 and for a longer period towards the end of 2020. In the meantime, the team changed as new people came on board as we realized the new and original ways we could create the things we needed.

V. A. – Maria Corvera Vargas was one of them. I read about her in a magazine: she’s a Bolivian indigenous fashion designer who makes clothes from leftovers of big brands, a pioneer in recycling. I went to her shop and convinced her to join our adventure. In the same way I met Rilda Paco, a Bolivian illustrator. She caught my attention for a controversial story against the Church that she created, and I adored the indigenous way in which she told it. I called her and she came to Cochabamba. She didn’t even understand what it meant to draw in virtual reality… she was really scared at first, and had to take pills not to throw up. [laughs]

What were the biggest challenges that you had to face for Prison X?

ROLY ELIAS – I live in Sidney and I have travelled the world a lot for my work as a sound engineer in live music. But I had never worked with Violeta before. I remember that she showed me a piece of her work, one day, and I thought: “It’s a bit too static, is there even any movement allowed?” [laughs]

A. P. – We had some technical challenges to get over this. The characters were extremely detailed, so we had very heavy models that we were trying to show in VR. They were also completely illustrated so they didn’t follow the usual rigging rules for 3D characters. That’s why I was trying to convince Violeta to not bother with motion. I admit I was a bit scared, at first, about going down that route. At the time the work was totally static, so it almost looked like a comic book.

V. A. – It was very beautiful… but without movements there was really nothing to see! So I said to Alap, “I’m going to make them move!” and we jumped into this challenge together.

R. E. – We needed to work on rigging. Rigging is something we do in live music too but the rigging you need for this kind of VR work is of a different type, so it was hard at the beginning. We were trying to optimize this very heavy characters and when they finally appeared they looked totally ugly! [laughs] So, each time we had to go back to the beginning, re-contact Maria and ask her for a new design. She would make it with the features we wanted, trying to overcome the previous problems, then contact Rilda, our 3D illustrator, and Rilda would create it all over again and send it back to us. At that point we would start again with rigging and so on. We did so much, in such a short period of time….

V. A. – Indeed, a lot of our budget went into trying to figure out the pipeline. It was very complicated at first. At some point we finally decided to buy a Rokoko [suit for motion capture], but it took us months to get here!

The main problem, I think, is that technology is very male orientated. It’s not intuitive for women. It goes from A to B to C to D. I love Alap because he was able to go from A to B to E and then back to C. He got his results in the most creative ways and this is amazing because, to me, rules are there to be broken. We could have not created a work like Prison X by following pre-established directions.

Alap, what made you decide to join Prison X as lead developer?

A. P. – I loved the ambition behind the project. I’ve always wanted to create something like this. It’s not easy to build a world where you don’t have to limit the user and allow them to walk all around. It’s something that no other experience before has allowed me to do. My frustration with VR in general is that in many projects I’m still forced to keep people on a specific path that is decided by the creator. I would just watch a movie if that’s what I wanted! What we did was certainly a technical challenge, and I knew I would have to learn new things to create it, but that’s the beauty of this medium. After all, if you stop learning, you’re dead.

Another significant reason why this project caught my attention is that the team came from Bolivia. I’ve only ever worked with people from the US, before, so to me all this was also culturally exciting. I’m from India and we, too, leave in a post-colonial reality. It’s something that makes me feel connected to the team, to the story we’re trying to tell and to the way we tell it.

A relevant topic you often mention in interviews is the standardization of stories. Could you tell us more about this concept?

V. A. – I believe that we are working against a techno-autoritarian future, a future that for me is a bit boring. I don’t want to make Frozen. I’m not even interested in making Coco, which is a Mexican story but told by Disney. It bores me to find the same passion, the same ideas, the same ways of telling a story – from beginning to middle to end – that we see every day in Hollywood, on television, on Netflix, even on Tik Tok. Everything is about appearance, everything looks exactly the same, even feelings are always the same. So, my idea is to use VR to create the kind of stories I grew up with. Which are the stories that I couldn’t capture with my camera, but that we still need and still believe in as a community.

In this way, VR can really become a tool to democratize animation. The characters you see? They are my characters, the characters of my people. Not beautifully-shaped things in which I don’t recognize myself. I wanted a woman who looked like my grandmother! I wanted the old lady to be like all old ladies, lying about her true age! Even the Australian man who is doing a documentary inside the prison, wearing a poncho that says “Better than yours” and thinking that he’s there to save everyone, is basically inspired by my own partner, a white Australian, and by the way I understand his psychology… and mine too.

The biggest struggle for our future is not even being able to tell our own story – that’s a bit of a cliché these days. Rather, it’s telling the story in our own way. With the narrative functions we use, our aesthetics, the designs with which we feel represented. At one point, Rilda said, “I cannot make a cloud from Cochabamba, because I am from La Paz! And La Paz clouds are different from the clouds of Cochabamba!”. This is the level of detail I’m talking about, the level of detail we’re trying to understand and to convey. I don’t want a cloud that looks like a United States cloud, because ours look different.

This is something that gives Prison X a new, different flavor.

V. A. – We wanted to represent the mythology of our stories and the elements or our lives… but all this also came in handy in dealing with the technological limitations we encountered. The masks are an example. It’s very difficult to get a mockup of a face. We did it with The Jaguaress, but it required a lot of work. Even in Hollywood stories, the faces are often horrible! They don’t look believable to me. And that’s what made me realize that I could use our masks in a clever way to avoid the problem. During Carnival, men and women wear masks similar to the ones I created for Prison X. When they talk to you, you don’t notice their mouths moving because the materials the masks are made of are very strong. This is what happens in Prison X as well: you see static masks, they cover the face, and this is both culturally correct and a way to make things easier for us technically.

But we also did the opposite: we used technology to convey conceptual ideas. For example, the jaguars move on their own because we started playing with AI for them. We didn’t do it for the AI itself, but because it made sense for the characters: jaguars are animals, they speak a different language, you shouldn’t be able to control them, they should control themselves.

Representation is an important part of this work. What can you tell us about it?

V. A. – Although in this fantasy dream you can see mythological ideas and stories and characters that represent America’s oldest culture, the indigenous Bolivians, I am not here to show outsiders my culture. This is not a museum I am creating. And I’m not even here to celebrate the differences, even if those differences need to be respected. What I want is to play with my own characters, my dreams, my nightmares for the sake of my imagination, for the sake of my daughter’s, for the sake of all Quechuan children who need to recognize themselves in the stories we tell. Prison X is a love letter to my own country, to the Quechuan and Aymaran, and to the indigenous people of the Americas.

A. P. – It’s amazing to work on a story where the aesthetics, the philosophy, even the process is not standardized. An example: you can’t quickly prototype anything that needs to feel Indian because if you go to asset stores, the assets you find there are probably made by Western people. A studio I worked for years ago wanted me to create a bank of 3D assets made by Indians and based on Indian sceneries, environment, objects and all that. It’s impossible to capture the feeling of a country in other ways. It’s a long process, but we need to start building these banks from scratch, so that other artists can use them and create works that really feel like the places and stories they want to talk about.

V. A. – You notice this problem with characters, too. Rilda had a hard time trying to figure out their skin color and the only one she thinks she did got right is Nuna. The palette was always too light, too dark, too brown, not enough yellow… And it gets even worse when you consider the body shapes: our bodies are bigger at the top, smaller at the bottom and it’s difficult to represent us correctly with the way technology is now.

R. E. – An example of the importance of representation comes from a friend of mine. He’s from Peru and when he watched the experience he was shocked by how much the storytelling got to him. He felt at ease throughout the whole experience: laughing, commenting on the perfect look of the bus, the perfect song that was played, how the plaza looked realistic… he even yelled at some virtual people to sell him some chicken! The prison that for some Australian users was a difficult place to be in – at least till they noticed the white director that physically looked like them – was a comfortable place for him.

This friend at some point noticed one of the characters. This character wasn’t even animated, but he still resonated with him. He felt connected with this guy somehow, because he reminded him of someone he went to school with: same look, same clothes, same attitude. He almost thought we knew him and based our character on him… but, simply, our characters look Bolivians, look Peruvians, look like South Americans… So, the amount of detail that goes into their creation is so specific and so accurate that people do feel represented. Which is something that rarely happens within our community.

The music and sounds are also very well-curated elements.

R. E. – The creation of sound was an interesting process. We wanted to work on it ourselves and for it to be as true as possible to what I believe that world sounds like and what I would hear in that specific plaza. That’s why I sent my cousin there: to record those sounds directly. He had six recording stations around the square, and when we worked on what he recorded, we tried to make it as real as possible. Even with the software, we were very careful in the way we approached it. We also needed the sounds to be realistic in the way they were physically perceived by the user. Working with live bands, I’m expected to trust myself and my ears, and I used the same approach here, balancing and implementing sounds when I thought it was needed and manually correcting the direction I heard them coming from.

V. A. – We also played with common day objects. Kojo [Owusu-Ansah, music producer and audio engineer] is part of our creative team. He is a sound artist that creates sounds from anything. We went together to the supermarket and started playing with tomatoes to see what they sounded like and if we could use that sound for the moment when you turn into Inti. It was such a trial-and-error process. I could have just called a VR studio to do the work, but that was not what I wanted. I’m an artist, I like to push myself, to create new things. And sure, it was challenging, but it was also beautiful. It still is.

Another interesting element is the music we used in Prison X. XNYWOLF is a DJ who I knew from Lemonade. I really like his mixes, and I was sure he was the perfect person for this piece, even if he had never written music for films. He sent me a demo and it was amazing because he created it using jungle sounds, and these sounds really transported you where the jaguars are… He also used part of a song called “Atahuallpa”, which means “Our last Inca”. Kala Marka, the folk group that created the song was speaking out against the standardization of images as far back as 30 years ago and that, to me, is incredible. There was a kind of synchronicity in everything we did.

Where is Prison X today?

V. A. – Prison X is in a beta testing phase right now, it’s not even optimized yet, so it’s still quite heavy. We’re figuring out the pipelines as we go. But, I think, no studio could have done this story and understand it in the way we wanted it to be. We are all first-timers in VR or in some of the tools we used for this work, and I think that made a difference, because we had to dig into our own experiences and backgrounds to find new ways to approach this technology.

I worked in a theater company when I was very young and I’ve written for theater as well, and I think that really helped me with the staging of this piece, and with understanding user engagement and user experience from an actual user experience perspective. But that’s also something that Roly helped us with: working with real-life bands, he has an understanding of what the user experience is like in real life. And that’s what we wanted: a user experience based on real life, not on an idea we had of reality.

Maria is another example. She’s a fashion designer with a very successful brand. She can create entire collections from small leftovers. Limitations made her look for new solutions and this is something she applied to VR too. So, all our limitations became our strengths because they were all we had. And they pushed us to think outside the box.

What’s the relationship between the audience and the narrative in Prison X?

A. P. – There is a fine balance between pushing the story forward and letting the user go through it at their own pace. The freedom, in Prison X, is an illusion. Before you get into the prison, you have a more-or-less straightforward linear narrative. Then you meet a more open world and finally you are led back to our ending and, again, to a narrative that is more linear. We trick you into that with the phone call you hear at the end. But, the main part, the prison, is the place where there is the most potential, and it’s mostly untapped. It’s where all the stories will be told and an exciting place for us to focus on, right now.

What is the future of Prison X?

R. E. – For Sundance we had to close some of the rooms that you could visit, so we limited our “open world” a bit, but the plan for the future is definitely to expand on it, to let people find their own narratives. We’ll keep testing Prison X in that direction.

V. A. – I already have over 90 pages of script. Characters, storylines… My idea for the future is to randomly assign you a character at the beginning of the experience and then let you explore the prison on your own for as long as you want, and discover the different interactive possibilities. And when we feel it’s time, we get the call going and bring you back to our finale. Each person will have a totally different experience: you can be a different character every time… or you can be the same, but explore other roads. That’s where I see the future of Prison X going, because that’s the whole point of creating this piece using this technology. If not, we would have just created a flat TV experience.

A. P. – After all, each person brings their meanings and ideas and feelings to any work they experience. How much, as an artist, can you leave a story open to interpretations and how much do you convey your own message and values and themes? Do you let the audience choose their direction or do you lead them your way? That’s what participatory culture is about and something that Prison X could really confront you with, in the future.

Prison X is a work created by Violeta Ayala from UNITED NOTIONS FILM and is produced with the support of Screen Australia, Screen NSW, Sundance Film Institute, MIT ODL and CPH LAB. Updates about it can be found on the official website and on the official Instagram account.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.